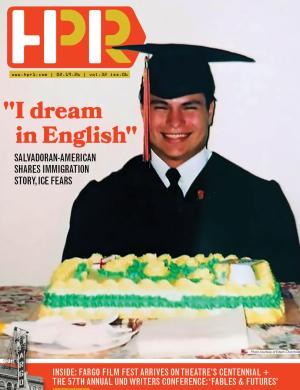

Salvadoran-American shares immigration story, ICE fears

February 16th, 2026

By Bryce Vincent Haugen

By his own account, Edwin Chinchilla is lucky to still be in the United States.

As a 12-year-old Salvadoran, he and his brother were packed into a semi with a couple dozen other people and given fake documents before making the arduous trip from El Salvador to the U.S.-Mexico border at Tijuana with the help of a coyote — common parlance for a human trafficker in Latin America. There, joined by an older woman he pretended was his grandma, he entered the United States for the first and — so far, only — time.

As someone who spent a good chunk of his life as an undocumented immigrant, Chinchilla is very much opposed to the activities of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Border Patrol, especially in the Twin Cities. He knows at least 15 undocumented people in the Fargo-Moorhead area and is fearful they will be ripped from their homes and lives in this community, where they are just seeking a better life, and sent back to dangerous situations in Latin America. El Salvador, in particular, is ruled in many places by MS-13, a brutal gang that demands “rent” for protection.

“I think ICE is bullshit,” Chinchilla said. “I don’t like (Trump). I’m glad nothing’s happened to myself (now an American citizen) but it’s affected my family, a lot of families. All I want is peace and happiness.”

But the problem is not new. Presidents Clinton, Bush, Obama and Biden also deported millions of undocumented immigrants, Chinchilla noted, many of them without criminal records.

“It seems now that white people are getting shot, now it’s a big deal,” Chinchilla said, referring to the deaths of protestors Alex Pretti and Renee Good at the hands of federal agents in Minneapolis.

Born without a birth certificate in Guatemala in 1983 to a 14-year-old mother and 18-year-old father, Chinchilla grew up on his grandparents' farm near Santa Ana, El Salvador. Hoping to make money to send back for a more comfortable life for their two children, Chinchilla’s parents both left for the United States before he was three years old.

“If I want to make a better life for my family, I’ve got to go to the U.S.,” Chinchilla said. “That’s the mentality that my dad had.”

School kids in El Salvador could be mean, making fun of Edwin and his brother Omar for being abandoned by their parents. His teachers stood in as parental figures. He and his brother bounced from home to home among family members.

“It sucked,” Chinchilla recalls. “It was hard not having my parents. Everybody needs their parents.”

In 1995, Chinchilla’s father — by now remarried, with two more kids and firmly established in the United States — sent for his oldest two boys and paid for them to make the expensive and dangerous trip north. Chinchilla, having worked on the farm growing corn and beans since he was 7, was reluctant to leave everything he knew for a strange new land. But at that age, it wasn’t his choice.

After arriving in…

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)

__293px-wide.png)