Arts | June 24th, 2019

BISMARCK – Six months of preparation boiled down to eight seconds. There were wet plate photographs to capture, a well-known Congresswoman from New Mexico to pick up, reporters to please, and… wait… Representative Debra Haaland’s flight was cancelled? The forecast was for rain? Who was arranging refreshments for the book signing ceremony?

Shane Balkowitsch paced back and forth in his natural light wet plate studio, the only one of its kind in the United States, sometimes disappearing behind the dark room revolving door. South Dakota Representative Tamara “Pleasant Woman” St. John of the Sisseton Wahpeton Sioux Tribe had already had her wet plate captured; she spoke with historian Vine “Lone Wolf” Marks about his flute, a family heirloom on one side of the room.

On the other side seated in front of Balkowitsch’s desk sat Bonnie, his wife. She joked good-naturedly about June 23, the day her husband’s first photographic book, “Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective (Volume I),” was released being their wedding anniversary. Hundreds of people were involved behind Balkowitsch’s book signing ceremony, he didn’t want to let them down, but capturing Debra Haaland’s wet plate was foremost on his mind.

Two hours before the ceremony was set to begin, Haaland, one of the first Native women to be elected to Congress in New Mexico, arrived. She was greeted warmly with gifts and hugs before quickly being ushered into the dressing room.

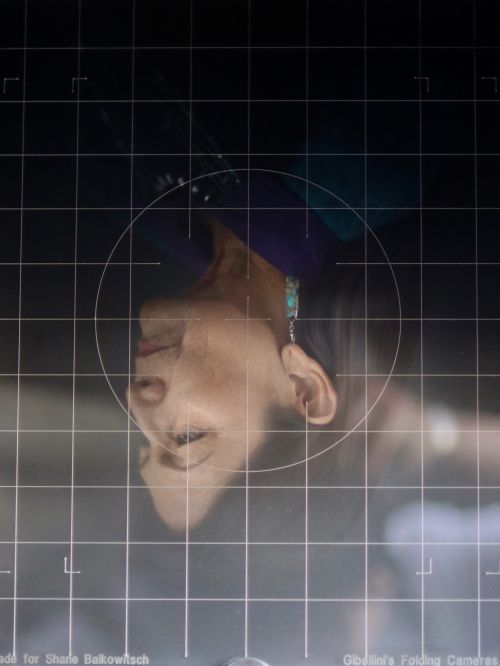

Balkowitsch disappeared again into his dark room while his assistant, Margaret Gonzalez Yellowbird, made sure the Congresswoman was in perfect position. He returned with the plate dipped in silver nitrate, took a deep breath.

“We are blessed with light today,” Balkowitsch said to Haaland, whose Native name means Crushed Turquoise in English. “I don’t think about this as a picture, I think of this romantically. I think of it as a 10-second movie. Your heart will beat eight times, you will breathe, and all that will be caught on the wet plate.”

Balkowitsch ducked under the dark cloth for final adjustments, slid the plate in place, then snagged his stopwatch after a light reading. Eight seconds. Balkowitsch’s friend and fellow photographer from Cleveland, Ohio, Herbert Ascherman Jr., agreed.

“Relax.” Ascherman said to Haaland. “How often do you get to be the absolute center of attention?”

“More often than you can imagine,” Haaland, a Democrat and a registered member of the Pueblo of Laguna Tribe said. She is one of many Native women across the country elected to public office in 2018, and she is someone who Balkowitsch has wanted to photograph since he knew about her campaign for office.

“Blink for me, blink for me,” Balkowitsch said. He then took away the lens cap and began counting. A sitter must remain completely still during the wet plate photographic process. Blinking may blur the eyes.

“One, two.”

He was in his zone, capturing a total of four images that immortalized Congresswomen Debra Haaland onto glass plates. One plate will be sent to the Historical Society of New Mexico and another to the North Dakota Heritage Center.

“Three, four, five. Listen to my voice, I’ll take you through this.”

Six months of planning, the nervousness of herding caterers, museum curators, organizing multiple politicians, Native speakers, dancers, drummers, and of course, the publication of his first book in a series of four, drained away from Balkowitsch’s face while he counted down.

He smiled when it was over. “Okay, we got the plate. Everyone give her a hand.”

The most important aspect of the day was capturing wet plate photographs of not only Haaland, but of St. John, and Marks, he said.

“All of this work, all of this thought, for 20 seconds of time, for two portraits,” Balkowitsch said. “Why all the effort for 20 seconds? Because it will give me two plates of silver that will last longer than anything else I have ever done. When we’re done – dead and buried – these plates will live on.”

What began with a nervous telephone call in 2016 to the great grandson of Sitting Bull, Ernie La Pointe, ended on Sunday afternoon at the North Dakota Heritage Center with the publication of his first photographic portraits of Native people. LaPointe is featured on the cover in a wet plate photograph entitled “Eternal Field.”

“I looked at it as one day Shane is going to be among the greats because he is telling the story of Native Americans in photographs,” LaPointe said. “Many non-Natives write about our history, but you can’t misconstrue a picture. I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t believe in what he is doing.”

Balkowitsch plans on continuing the series by taking a total of 1,000 wet plate photographs, he said. He never adds anything to his photographs of Native people but what they bring themselves: family heirlooms, ornate headdresses, flutes, animal skins, or any other type of regalia considered sacred and a part of their culture, or, they could arrive in blue jeans and a T-shirt. He leaves the decision of how they want to be photographed and remembered up to his sitters.

“It’s epic,” Tamara St. John said during the ceremony. “The objects people bring to these photos are a part of our people. With this project I thought about how it can affect the future. I can only argue that the generations to come will be equally amazed.”

“Classical methodology, contemporary vision,” Herbert Ascherman said. He noticed Balkowitsch’s work and traveled to North Dakota on several occasions because he believes the project is important. “Combining the two produces an artifact, an heirloom, a touchstone to the past here in the present.”

Media reports of Indigenous people in America usually focuses on crime, poverty, or misfortune, Debra Haaland said. Balkowitsch’s work breaks stereotypes, raises the visibility of Natives in America in an honest way.

“Too often we are portrayed as frozen in time or extinct,” Haaland said. “We’re portrayed as legends that keep North Americans immortalized in the past, notions that say we are extinct like the dinosaurs. This works to reframe the Indigenous story and it’s told by the people who know it best – us.”

“Native Americans are no longer frozen in time. We are still here. This is a testament of the unyielding endurance of Native peoples.”

For Representative Ruth Buffalo, of Fargo, a registered member of the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara Nation, Balkowitsch’s book spoke to her about the need to forgive, on all sides.

“Some of the common themes I think of is the rebuilding of our relationships here and up along the Missouri River,” Buffalo said. “And also the notion of forgiveness, and this is a step in the right direction.”

“This is my life’s work,” Balkowitsch said during his speech. “And if fate does not break my stride I will do everything I can to see this through.”

Known by the Hidatsa name Shadow Catcher, or Maa’ishda Tehixixi Agu’agshi, which was given to him during a naming ceremony by Three Affiliated Tribes historian Calvin Grinnell “Running Elk” in October 2018, Balkowitsch will need a decade to reach his goal of 1,000 wet plate photographs, he said.

“This man stood up and became a warrior in his lifetime,” Allan Demaray, a member of the Three Affiliated Tribes said of Balkowitsch. “He has helped unite many people from many nations and made the world a better place. He has found a way to capture that beauty for generations."

Balkowitsch’s book entitled “Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective (Volume I)”is a limited edition, and can be purchased online. Balkowitsch personally signs all 1,000 books currently up for sale. Sales from the book will benefit the American Indian College Fund.

February 16th 2026

January 12th 2026

January 12th 2026

December 18th 2025

October 28th 2025

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)