Arts | December 12th, 2018

SEBEKA, Minnesota – Nearly a century ago the nation was racked by inclement weather, soaring unemployment, and despair following World War I and the lucrative Roaring 20s. The 1930s were an era of dust storms and lunch lines, where banks closed and Wall Street brokers leaped to their deaths from New York City’s “suicide pinnacle,” the Singer Building.

Under such chaos did then President Franklin Delano Roosevelt initiate the Public Works of Art Project in 1934. The government hired 3,749 artists for approximately $75 per artwork, producing 15,663 murals, prints, and sculptures across a depressed United States, according to the Smithsonian.

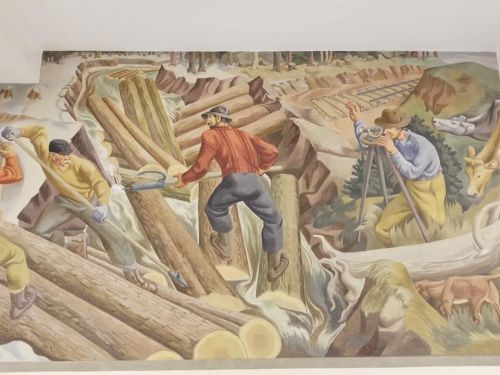

One such painting exists in Moorhead and is currently being saved. Another painting not so fortunate is a 72-foot-long 8.5 feet high mural, which faces destruction due to modernization, and an old and faulty heating system in Sebeka Public School.

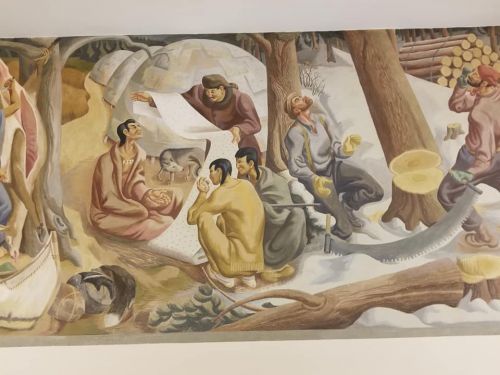

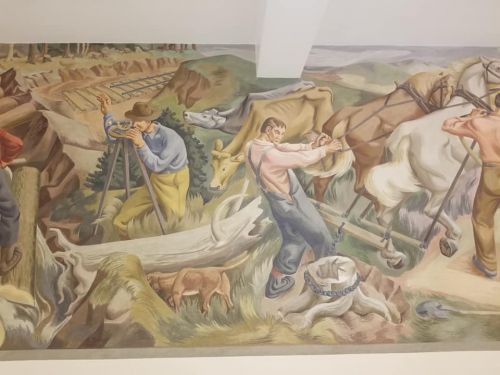

Painted in 1938 during the Great Depression the massive mural by Richard Haines depicts Native lifestyles before Europeans arrived, and then the ensuing colonization and conflict, with settlers farming and logging.

With masterful strokes and a budget of 500 gallons of paint, the painting is known as a Works Progress Administration’s, or WPA Federal Art Project mural of the New Deal era, according to WPA Murals, code an unusual discovery.

The mural was painted in a rarely traveled second floor school hallway, and is in pristine condition due to a lack of sunlight, but because of a faulty radiator heating system the artwork must be moved or possibly destroyed to make way for a gymnasium, Sebeka School District Superintendent David Fjeldheim said.

“We want to try and preserve it as best we possible could but we know it’s on a plaster and lath wall and we’ve been told that if we tried to tear that down and cut that out it would probably end up crumbling on us,” Fjeldheim said. “So we’re still looking into what our options are as to possibly preserve that as it is, but it sounds like it is going to be very difficult to do that.”

One option, he said, is to digitize the mural, which would then be placed back into the school after it is gutted for the new gymnasium. Plans for building modern classrooms with central heating away from the current school location are already underway. Sebeka Public School serves pre-kindergarten through high school, the school’s website reported.

“We’d love to preserve it and do what we can, but if we can’t preserve it then we’re going to have to probably digitize and make a tapestry of what it looks like,” Fjeldheim said. “And the ironic part of this is some depictions of Native Americans on there, in some arenas wouldn’t go over very well.”

WPA murals of that era were painted in social realism style, also known as WPA style, according to Markus Krueger, programming director for the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County. Social realism gave way after World War II to abstract expressionism, but during the Great Depression artists intended to reflect local history. Similar murals were made in schools and post offices across the country, including one in the old downtown Moorhead High School.

Tucked away behind makeshift partitions inside a locked second-floor storage closet, the Moorhead mural – painted on canvas by Lisa Wiley in 1939 – depicts Native and early pioneer life. Attempts are being made to save the painting.

The Sebeka mural is not as fortunate; it was painted on the wall’s plaster. Professionals would have to cut through a complicated mixture of wire and lath to remove the mural.

The three-story school intends to remove the classrooms on all floors to make way for the gymnasium, which proposes a difficult question: at what point should cultural history give way to modernization?

“Anything is possible,” Krueger said. “It’s safest to leave it preserved where it is. That’s an important art style in American history and in the history of our nation and our government’s relationship with the arts and the jobs program of trying to put people back to work. FDR believed it wasn’t just bricklayers we had to put back to work, it was also artists and painters. Putting them to work to tell our own local stories, and putting this artwork in public buildings in schools and post offices.”

Colin Turner, an art conservator of the non-profit conservation Midwest Art Conservation Center or MACC believes the mural can be saved, if the community and interested parties want it to be. Money and a place for the mural to “live” are two of the key ingredients.

“The WPA murals are an important part of American history,” Turner said. “As you can probably imagine the short answer is yes, anything can be saved, but it’s all a matter of cost and the community’s willingness to take on the task.”

“If it’s painted right on the wall it sounds particularly difficult, but it needs to be examined by professional conservators. WPA murals can be important not only from a community perspective but also a national perspective.”

The safest way to keep murals such as the one at Sebeka Public School is to keep it in place, Turner said.

“Is there a way to keep in place?” Turner said. “It was painted there, that is where it was intended to be, is there a way to keep it in that place that it stays right where it is? If you can leave it in place and still accomplish what they want to do with building that would be a logical solution.”

Keeping the mural in place would be the most cost effective method, and if done correctly the mural could have a more prominent role than before, Turner said.

“If it can stay in the same location and the building can be retrofitted to fit the needs of the community that would be one way to approach this.”

Any controversy included within the mural could become an educational experience for people if the painting is displayed correctly, Turner said.

The Minnesota Historical Society does offer grants to help with conservation, he said.

“Murals are tough,” Tom Braun, an art curator from the Minnesota Historical Society, said. “Most notably they are big and often not on a medium that are portable. There is probably a way to preserve it, it all gets down to how much is it going to cost, which would be probably a bit, and where will it is going to go. It would be hard to move something 70 some feet long.”

Larry Heitkamp, a concerned citizen who once lived on a farm near Sebeka was alerted to the possibility of the mural’s destruction and said preserving such art is more than preserving history, it is a patriotic duty.

“This art tells the story of the workers who built this country,” Heitkamp said. “There is a great fallacy being spread that ‘we the people’ do not have money to pay our obligations to the people, such as Social Security and Medicare. There is a misconception that we don't have the money to maintain infrastructure, so we are going to allow the infrastructure put in place to keep costs down, to be privatized, which in turn will raise the cost of doing business.

“That misconception spills over to we don't have the money to honor our history. It must be torn down to pave the way for the future. If we don't fight to keep these social achievements, we dishonor the workers who fought and died to make this nation great. We dishonor our founding fathers.”

Haines, called a “Midcentury Master” by California’s Sullivan Goss, an American Gallery, was born in Marion, Iowa, and later studied at the Minneapolis School of Art where he would become a teacher. In 1933 he won the Vanderlip Traveling Scholarship to Fontainebleau, France, to study mural painting. Shortly after his return he became involved in New Deal art projects winning nine mural commissions between 1935 until 1941. In 1952 he was among nine artists selected to paint murals for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. Haines also won many prestigious awards and died in Los Angeles on October 9, 1984.

The Office of the Inspector General and the U.S. General Services Administration work to identify and recover lost works of art particularly from the New Deal era federal art programs, according to the GSA’s website. Such artwork could be considered to be federal property and all art possessors are requested to maintain care of the artwork until any title research is completed. If WPA artwork is determined to be federal property, then the GSA works with the possessor to return the work of art to federal custody with the ultimate goal of properly displaying the piece in a qualifying institution.

Office of the Inspector General Assistant Special Agent in Charge Eric D. Radwick was contacted for information, but did not reply by press time.

February 16th 2026

January 12th 2026

January 12th 2026

December 18th 2025

October 28th 2025

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)