Arts | December 5th, 2018

“If I go to France and eat French food and write like the French. When I was in Yugoslavia I was working as a Yugoslavian. When I went to Paris for three years I worked with a French influence. Then I came here and I become American and work as American. This multiple personality might be drastic to somebody who look from the outside but to me, they’re all familiar to me. It’s not a drastic change.” said the twin cities based, Yugoslavian born artist Zoran Mojsilov.

He went on to say, “Even when I’m in Serbia now my work from city to village change because my surroundings change my work and I hope change me too. In Serbia, we have this phrase, old tree doesn’t bend, but I am the special tree. I can still bend--I do yoga.”

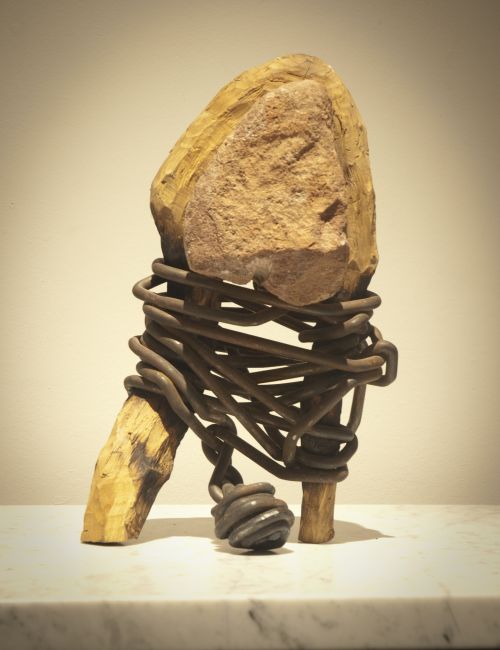

Yoga was a topic that came up a few times during our interview as we sat among his sculptures prior to the opening of his current exhibit at the Plains Art Museum. He was large in stature, it wasn’t hard to believe he was once a champion Yugoslavian Greco Roman wrestler. Now instead of grappling with other wrestlers, he grapples with metal, wood, and stone.

A lifetime of working on these physically demanding large-scale assemblages takes a huge toll on Mojsilov’s body.

He regularly practices yoga has even worked out a deal with his masseuse to exchange his work for her work. “It is physical, you know? I said to young artists, watch what you wish--it might come true! Look at my case, breaking stones for the rest of my life, like in the prison and I’m innocent!” He laughed and continued, “It might look like punishment for somebody.”

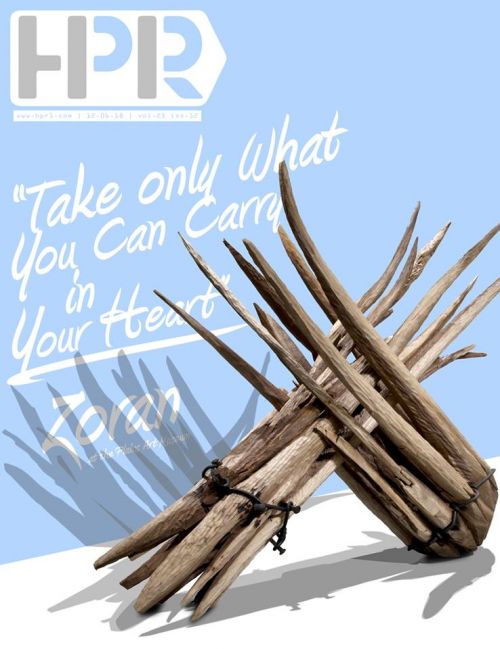

Mojsilov’s large-scale wooden assemblages that make up “Time Machine” not only serve as a tribute to his life’s work and the inspiration that he’s found on his travels but are also rife with recognizing and embracing his Yugoslavian identity through the folk imagery and pre-Christian symbolism that has been woven into the iconic Pirot carpets that have been recognized as a Serbian national treasure. As we talk he pulls up his shirt sleeve to reveal a Pirot tattoo that wraps around his forearm.

The carpets are geographically protected meaning they can only be produced in the Pirot area and with the wool of Pirot sheep. The carpets are handmade using the same tools and processes that were used generations ago. The carpets once filled Serbian royal palaces and the homes of the elite. They are instantly recognizable with their bold geometric patterns and their thin but dense construction.

Mojsilov is not a fiber artist by any means but he incorporated the imagery into his work through carving or staining them onto the wooden surfaces of his sculptures. Though, he does have a Pirot carpet on the gallery wall alongside his work, and to reference “The Big Lebowski,” it really ties the room together… in terms of symbolism, context and posterity.

Though Mojsilov didn’t always appreciate the ancient symbolic tradition of the Pirot carpet, he says he developed a fascination with the symbols and started studying them within the last five years as he traveled back and forth from Serbia to the United States.

Though he was born in Belgrade he spent his summers with his grandmother in the village of Vlasi. In 2012 he got reacquainted with a childhood friend during one of his visits to Serbia (formerly  Yugoslavia), this friend was a documentary filmmaker and documented his experience returning to the village and revisiting a large-scale public art piece that he constructed the summer prior from old farm tools donated by the villagers. Upon his return, there was no trace of the sculpture. It turned out that the metal had been scrapped and the wood was burned and used to fuel the locals’ plum brandy stills.

Yugoslavia), this friend was a documentary filmmaker and documented his experience returning to the village and revisiting a large-scale public art piece that he constructed the summer prior from old farm tools donated by the villagers. Upon his return, there was no trace of the sculpture. It turned out that the metal had been scrapped and the wood was burned and used to fuel the locals’ plum brandy stills.

“They didn’t just burn it, they made a batch of plum brandy out of my work.” He went on to say, “My work went from spiritual to spirits!” At first, he was incensed but he learned that he had to let it go and that if he created something it had to be something the people could use and relate to.

So in 2014 he successfully launched a Kickstarter campaign called, “Life from art in Vlasi” to restore and reactivate the village mill, which was once the lifeblood of the community. With the help of his friends who were professors and engineers at the University of Minnesota, they revived the nearby dam in the picturesque mountain valley and repurposed the flour mill to an electric generator. The city of Pirot has even donated the old elementary school to house a permanent collection of his work.

Aside from his work in Serbia, his work can be found in public and private collections throughout the world.

Aside from his work in Serbia, his work can be found in public and private collections throughout the world.

“Time Machine” spans 40 years of the artist’s work. “This was supposed to be something to relate to the refugees. So you walk between these machines and you can get caught, this time machine as war, or this or that, the symbols may be protecting you maybe--maybe not.”

One of his smaller scale pieces on exhibit was a collaboration with friend and regional author, Louise Erdrich. It is a woodblock print featuring Pirot imagery and a short poem that reads, “Gather yourself in darkness, take only what you can carry in your heart.”

As we walked past his piece titled, “Tilt and catapult,” he mentioned that that was the reason he left Yugoslavia. It’s a 14-foot wooden installation with three exquisitely carved representations of a figure each suspended at different lengths. The statement surrounding the piece addresses how people deal with trauma. It’s the depiction of a man’s metamorphosis or rather a rebirth.

In the early 80s, Mojsilov worked as an art therapist at a military psychiatric hospital in Yugoslavia. Interestingly enough, this piece would have earned Mojsilov the award for “Best young sculptor” in the 1983 Oktoborski Salon, a prestigious art show featuring the work of young artists. It turned out that the government rejected to exhibit the piece due to its subject matter.

“The news I got was I was rejected from that show. One of my friends was a judge--one of many for that salon and she said sorry Zoran, you don’t know the story. You were chosen for the first prize for young artist. We just voted unanimously, then the director said you can not show here.” He said.

Mojsilov’s reaction? “After that, I said you can go to hell everybody.”

So he packed up his sculpture in cardboard and bought a one-way ticket to Paris, and that piece has been with him ever since. Once in Paris, he participated in a multi-disciplinary art residency through Association Confluences. Here he met and married American artist Ilene Krug and returned to St. Paul Minnesota with her in 1986.

Zoran spoke about how each place he lived inspired his work, so we couldn’t help but ask what inspires him in the midwest. He said the rock piles and boulders often found in farmers’ fields. Many of those farmers are relieved when Zoran relieves them of their rock piles. He joked about how many of the locals will refer to the stones as “spring flowers” because they are pushed to the surface due to the thaw. “In a way, we are also collaborating. They don’t like stones -- I like stones. So everybody’s happy.” he said.

YOU SHOULD KNOW:

Time Machine will be on exhibit through May 25, 2019

Plains Art Museum, 704 1st Ave. N, Fargo

February 23rd 2026

February 23rd 2026

February 16th 2026

January 12th 2026

January 12th 2026

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)