Culture | May 12th, 2016

__250-wide.jpg)

By C.S. Hagen

Late at night, the north wind whistles through the Houston House cracks. Raindrops – tiny footsteps to the imagination – flick against the 135-year-old frame, now fitted with aluminum siding.

Darkness retreats reluctantly under a lantern’s light revealing Victorian opulence: fine lace curtains, a dusty gilt leather-bound Bible, thick as a set of encyclopedias, an Art Deco mahogany bookshelf towering above parlor chairs, a pump organ sitting silently and opposite a medieval hunting tapestry. A once-plush couch hugs a polar bear rug, its death grin sparkles before slipping back into the shadows.

Above the ornate walnut staircase from a second floor bedroom, a floorboard creaks. Rumors the Houston House, built by David Henderson Houston Sr., is haunted become momentary fact as breath mists before the eyes.

Workers and visitors to Bonanzaville Village, a sprawling museum dedicated to North Dakota history, have reported instances of hearing children laughing inside the Houston House in the middle of winter, when no children were anywhere near.

Ghost hunters visited the house three years ago and found evidence the homestead and a nearby tavern and one-time brothel named the Brass Rail Saloon, had paranormal activity, according to Brenda Warren, Bonanzaville’s executive director.

“In the upstairs southeast bedroom of the Houston House there is always an indentation in the pillow,” Brenda said. She has worked at Bonanzaville for three years. “And I always fluff it back up. When I come back to check on things there is always the same indentation in that pillow.

“I’ve never really believed in the paranormal; however, this keeps happening over and over again,” Brenda said. “So it makes me wonder if maybe there might be something there.”

The room is where Houston, a former inventor, farmer and poet, and hailed as one of Cass County’s most remarkable citizens, died from a brain hemorrhage after becoming lost in a blizzard in 1906, museum records report. Mental torment, which stemmed not only from the blizzard, but also from watching his life’s work ripped away from him by corporate giants, contributed to his death, according to museum records.

Missy Warren, Brenda’s daughter and the special events and wedding coordinator at the museum, is fascinated by the Houston House. “It’s my favorite structure on the premises, hands down, because of all the beautiful pieces in it. It adds a lot to the ambiance to know that people have heard and seen things in that house. I really do believe that if there is a spirit, it is a very kind and patient spirit.”

Missy once heard a loud noise inside the Brass Rail Saloon, which to this day gives her the shivers. “There is something in the saloon, and everything that has been heard has come from the upstairs, where it was most likely once a brothel.”

If ghosts exist, and return to the land of the living because of unfinished business, then the Houston House is at the very least a viable setting, both Brenda and Missy agreed.

Houston the man

He was born in Glasgow, Scotland in 1841, and immigrated with his family via New York City to Wisconsin in 1841 when he was three years old, according to a 1900 edition of the Compendium of History and Biography. Houston moved to the Cass County area, outside of Hunter, North Dakota, alone, when he was 38 years old and fell in love with the windswept Dakota Territory plains, at a time when buffalos and Native Americans still roamed freely, according to his niece-in-law Mina Fisher Hammer in her 1940 book ‘The History of Kodak and its Continuations.’

A diminutive figure, bespectacled and bearded, a reader of the classics, studious and reclusive, he never attended church, but took pleasure in long walks at dawn, and working not only with the earth and his skills at farming, but beneath it, in a cyclone shelter, to further his photographic inventions.

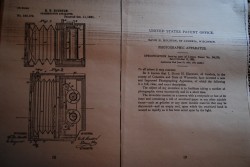

Houston’s first patent was filed in 1867 for a camera invention. A total of 21 patents, including the roll-film mechanism, which was to become the heart of the Kodak camera, were also invented and patented by Houston, according to patent records available at Bonanzaville. He sold the roll-film mechanism patent to George Eastman, the controversial owner of the name Kodak, for $5,700, according to patent records.

Neighbors thought Houston a “little funny,” according to a 1987 edition of The Highlander, but he was soon to become the envy of the land. Preferring quiet to satisfy his curious mind, he didn’t marry until he was 47, after his growing fortunes allowed him to build the Houston House, half of which was moved to Bonanzaville in 1971. He married 23-year-old Annie Laurie Prentiss, a longhaired beauty with flashing black eyes, perfect features, vivacious and daring, according to museum records. Annie was his exact opposite in every way. She was a music teacher, loved the most modern fashions, the piano, and was seen frequently racing trains with her buggy and pair of Hambletonian horses.

Life for the newlyweds was merry in the first years, and became even merrier after Annie gave birth to a son, according to Hammer. The house was filled with parrots, sparkling kerosene lanterns, servants and maids, and was heated with the area’s only known furnace heater. Houston’s inventions, however, including farm plows and high-yielding grain seed, but most importantly his camera equipment, were never far from his mind.

“Hours, even a day and a night, would pass when one saw nothing of him,” Hunter wrote. “He was a dreamer, a seer.”

“All of the Houstons were spiritualists,” the article featuring the Houston family in The Highlander reported. “One room was used for séances. Mrs. Houston devised a type of shorthand to record words for the “other side,” which she claimed came too rapidly for shorthand.” Many of the slats used to record such messages were reportedly from Houston’s favorite poet, Robert Burns.

Annie began taking frequent trips into Fargo, where she was always bejeweled with diamonds and wore the most recent fashions. She wintered with their son, David Houston Jr. in Miami, Florida, leaving her husband alone, as was his wish, to continue his studies and inventions.

“She was lonely,” a neighbor was quoted saying about Annie in museum records. “Her days were awfully dull.”

Houston the forgotten inventor

As photographers, called Kodakers after Houston’s inventions helped spur the Eastman Kodak Company to international fame and fortune, became a portable device available for $25, Houston continued improving on his inventions.

Much like the dragon and its soft underbelly, genius always has an Achilles heel. Houston could invent magnificent equipment, but he could not control the entrepreneurs who sought to entrap him, and had no desire to manufacture for himself, according to Hammer.

During the following two decades, Houston became Eastman’s gadfly.

By 1886, Houston had sold all his patents to Eastman, for a collective total of $48,000, according to museum records. Eastman, on the other hand, created a monopoly, eventually wiping out all major competition through shrewd business deals and strong-armed lawsuits.

Thomas Edison, the inventor of the light bulb among other equipment, tried to take credit for Houston’s inventions. Edison and Eastman worked closely together, and to this day Edison is still credited with the invention of the moving camera, the forerunner of modern equipment and a giant leap from what was then known as the magic lantern. Without Houston’s roll film apparatus, however, there would never have been any portable or moving camera invented, at least, for some time.

“The roll film mechanism solved the magic lantern quest for animated photographs, but contained the basis for the moving picture as well,” Hammer wrote in her book. Houston’s soon-to-be controversial invention was designed to utilize a strip of film wound on a roll, which was then fed into an opposing spool as exposures were taken.

“He had the most uncanny genius for camera inventions that I have ever known,” Eastman said of Houston. And yet, despite owning Houston’s patents, Eastman refused to give Houston even partial credit for the invention that transformed the bulky cameras into handheld devices. According to a March 15, 1932 Minneapolis Tribune article on Eastman, Houston’s roll-film apparatus was considered “one of the company’s most valued assets.”

Houston’s loss of recognition for his inventions was also due in part to imperfect patent legislation, which protected the patent owner and not the inventor, according to Hammer.

Additionally, the origination of the name Kodak has been under debate since it was trademarked in 1888. Eastman refused to admit the word Kodak was Houston’s brainchild. Instead, Eastman said the word meant nothing, and that he had “pulled it out of thin air,” according to museum records including official press releases from the Eastman Kodak Company. The name was patented under Eastman’s name before Houston sold his patents.

“Houston named the invention [his first camera] Kodak, after the state of North Dakota, in 1880, then patented the device,” Hammer wrote. Hammer was witness to Houston’s mental anguish toward the end of his life, according to U.S. Patent Office records. “But because it is not permissible to patent the name of an invention, it was agreed that Eastman, after he took over Houston’s patent output, should register Kodak as a trademark – making him heir to the name.”

“Mr. Houston, of course, during the 1880s, realized that he was engulfed by forces beyond his control,” Hammer wrote. “He was not a fighter in such a sense. It was apparent to him that two courses lay open. He must fall in line, appease, or cease inventing.”

Invention was his life. He could not choose the latter, and eventually his patents were swallowed by Eastman’s ambitions to combine the portable camera and the flexible film concepts.

By the winter of 1906, Houston had already decided to end his camera inventions.

“Houston was so disillusioned over his treatment by Eastman that he ordered all his photographic inventions and cameras destroyed,” museum records report.

Houston died in his bed in the room open to tourists inside the Houston House at Bonanzaville. He left behind a modest estate, which was quickly divided up according to his wishes. The Houston House was split in two, passing through different owners until it eventually arrived in West Fargo’s Bonanzaville Village.

Eastman went on to create a company worth $200 million, according to the Minneapolis Tribune. He committed suicide by shooting himself in the heart on March 14, 1932.

Houston the ghost

As of April 26, 2016, a pillow inside the southeast room had a perfect human head’s indentation, as if someone taken a nap on it. Could it be Houston’s, or his son’s spirit, who died young while at sea? Or could it have been Annie Houston, the beautiful woman who unlike her talking parrots proved difficult to cage?

“If I had to choose anyone it would be Mr. Houston,” Missy said. “I feel he was ripped off to a certain extent. All the accusations came out and said he didn’t invent these things, but there is no solid proof that he didn’t invent.” Some newspaper and magazine articles attribute Houston’s inventions to a brother in Wisconsin, claiming that David Houston was only the patent lawyer.

The Eastman Kodak Company did not respond to requests for a response, but according to recent press releases, the company’s official position had not changed. Houston was not recognized officially for his inventions or for creating the name Kodak. Patent paperwork dating from the 19th century disagrees with the Eastman Kodak Company’s position.

“They were kind and giving people,” Missy said of the Houston family. Once, when a fire broke out in Hunter, North Dakota, Houston rushed to help, and being a landowner assisted anyone whose assets were harmed during the conflagration, museum records report.

“If David and Annie are still there,” Missy said, “so be it.”

May 12th 2025

May 12th 2025

July 15th 2025

July 3rd 2025

May 19th 2025

__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)