Culture | September 20th, 2017

When I travel I prefer to hit the backroads, exploring sleepy highways, scenic byways and hoping I don’t end up lost.

I found myself on Highway 21 heading west to Mott the spot and stumbled across The Stern Homestead. Its earthy construction grabbed my eye and upon closer inspection I saw informational placards provided by the National Register of Historic Places noting points of interest on the grounds. I turned around at the most convenient spot and stumbled upon a unique piece of history that offers valuable insight into the lives of a turn of the century German Russian farm family.

The Stern farm is an excellent example of a German Russian homestead.

Construction of the homestead started in 1905 and was finished in 1907. It's constructed with perfectly placed pieces of sandstone of various sizes.The stones came from south of the Stern property and were transported in a horse-drawn ‘stone boat,’ much like a sled but used to haul heavy objects like large stones or bales.

The Germans from Russia were notoriously resourceful and no strangers to earthen construction techniques. The mortar used during construction was more than likely made from a combination of clay, manure, straw and water.

Lumber for the inner walls of the house and the hayloft came from Glen Ullin which is 50 miles north of the homestead. The lumber hauled in by horse and wagon.

A 10x18’ kitchen was added in 1918. Fredricka Stern had a beautiful modern sink installed in that kitchen but ironically enough never had running water.

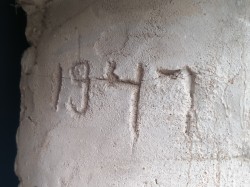

Their power was generated by a windmill built by John Stern. A layer of stucco was added to the exterior of the house in 1947. If you look closely on the inside of one of the barn windows you can see where someone wrote the date in the wet stucco 70 years ago. The roof was replaced in the 1950s. Though years of unapologetic prairie winds are taking their toll on that rooftop, the stone remains unmoved.

According to the Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, “Even though German-Russian architecture was a unique sight on the Dakota prairie, its overall simplicity of design and modest size reflected the lack of importance of the house as a status symbol in the German-Russian community. This extension of the treeless prairie required little imported material or outside labor to build. It was utilitarian in space and design and reflected the German-Russian attitude towards economy and utility.”

Aside from the building materials, they were known for connecting a livery stable to the house. Hay and grain were stored above the barn through a small door in the gabled roof and were forked into the trough below--which still has the bite marks of a destructive horse, years after the fact. Steel pails and wash basins stood undisturbed as I explored the cool damp building. Connecting the barn to the house wasn’t just practical during the harsh North Dakota winters. It was also energy efficient.

Fredricka lived on the farm until 1965 and many of her things are still there. Faded silk flowers decorated much of the living quarters; some original furniture; beautiful turn of the century wallpaper that looks as if it were hand printed--which is more than likely the case.

The wallboards and ceiling were painted a cheery robin’s egg blue. The German Russians were known for their colorful interiors. The WPA Guide to North Dakota which was published in 1938 cites brightly colored German Russian dwellings dotting certain parts of the state.

The farm had an artesian well on the property and was one of the factors that sold John Stern on the property during the Homestead act of 1862. After paying a $18 fee the 320 acre claim had to be farmed for five years and made livable. Before the present day house was built a small earthen sod house was built by the well, but prior to that John Stern found shelter under an overturned wagon while proving his claim. He and Fredricka were married the same year they started construction on their home.

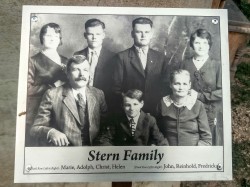

In the early years Fredricka lost a set of twins and a son before the cemeteries in Mott and Hettinger were established. The three children are buried in the Stern farmyard, the graves visible from the kitchen window. They went on to have five children: Marie, Adolph, Christ, Helen and Reinhold.

From 1910 to 1978, a line on the Northern Pacific Railroad ran from Mandan to Mott and would make daily stops at the Stern farm. There was a large water tank on the property that was used for the trains to cool their engines. Now all that is left is a railroad berm and a small metal sign with a “W” on it.

In the 1930s, when times were tough, it wasn’t uncommon for hobos to stow away on those trains. They had a complex language of signs and symbols that they would use to mark certain farmsteads as “friendly” or “unfriendly.” It was well known in hobo circles that they could get a hot meal at the Stern farm. Some would stay the night and help with farm chores in return.

Needless to say, it wasn’t the first time a curious traveller saw the sign and was drawn toward the Stern Homestead. The Mott Gallery of History & Art led its last tour through the house interior on August 27. Time is taking its toll on the aging structure and liability is becoming an issue. Though the grounds will  to be open for walking tours.

to be open for walking tours.

February 16th 2026

February 13th 2026

January 15th 2026

January 15th 2026

December 18th 2025

__293px-wide.png)

__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)