Culture | October 29th, 2014

By Aaron Barth

A couple days ago HPR’s J Earl Miller called to chat. In that conversation, we spoke about the Nov. 4 election, and also about what a person might do to motivate others to vote. We agreed that there was little we could do to motivate people to vote.

Our conversation turned toward history. I said to J that since history is a continuous sequence of causes and effects, it means that history, or research and knowledge of it, informs a voter today. This includes knowing the history behind a piece of legislation, and the history of a legislator who proposed the legislation.

The idea that history informs a voter was the driving theme of our conversation. To bring more insight to this I spoke with Tracy Potter, both a professional historian and a legislative candidate. In 2007, when Potter was a state senator (District 35 in Bismarck), he brought about the end of a co-habitation law in North Dakota. The origin of the law meant something to those who created it, as the co-habitation law came into existence with North Dakota's statehood in 1889.

Before North Dakota and South Dakota became states, the area was informally organized as Dakota Territory from 1861 until statehood in 1889. In the Territory, Anglo-American laws and institutions had yet to grab hold. Settler colonists came in one wave after another, and brought everything one might expect into a territory. This included the violent relocation of indigenous populations through military conquest and attempted genocide. During this process, federally-funded railroads also laid track to settle the landscape and bring it into agricultural production.

Military columns, railroad construction, bonanza farming and cattle ranching brought with it a large male workforce; and with this, prostitution followed. If we use our historical imagination, we can understand how the first state legislators might have wanted to clean up (in the moral sense) North Dakota. A way to do this, so they thought, was to create an anti-cohabitation law: make it illegal for a man and woman to live with one another unless they were married.

It is important to remember that, at that time, prohibition was the law of North Dakota, and women did not yet have the right to vote in the state, or the nation as a whole. "In 1889, the anti-cohabitation law," says Potter, "was originally aimed at the members of society who were thought of as despicable." We can speculate that the legislators who created the law did not intend for that law to apply to them, and this kind of speculation is not unfounded.

Historians are learning more and more that some of the most famous Anglo-American moralists of the second half of the 19th century were unable to adhere to their own standards. Or, if they had standards, they did not care or bother to apply them to themselves.

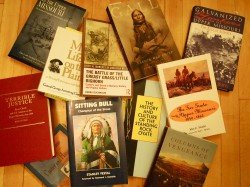

General Alfred Sully, a commanding officer in the US-Dakota Wars of 1863-64, took a Dakota woman as his wife during his military campaign, and children came of it. Vine Deloria, Jr., the Native author of “God is Red” (1972) and “Custer Died for Your Sins”(1969), is one descendant of that union. Vine's son, Philip Deloria, another historian and author of monographs such as “Playing Indian”(1998)and “Indians in Unexpected Places”(2004), is also a descendant.

In an Oct. 6, 2014 article in “Indian Country Today,” Native reporter and historian Adrian Jawort referenced Tim Lehman's 2010 work, “Bloodshed At Little Bighorn: Sitting Bull, Custer, and the Destinies of Nations.” Lehman built a case that George Armstrong Custer, then married to Libby, fathered a son with a Cheyenne woman. This is a contentious assertion, of course, since Custer was thought to have been sterile (one line of speculation is that his sterility was from spending all of those years in the cavalry saddle during the Civil War and in the American West).

When Theodore Roosevelt spent time in the Badlands of western North Dakota in the 1880s, he is known to have taken Native wives as well. Lakota Historian Dakota Goodhouse, enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, uncovered a Nov. 6, 1934 interview between an Arikara named Sand Hill Crane (a former scout for the U.S. Army too).

Sand Hill Crane gave an interview to U.S. Army Colonel Alfred Welch about Theodore Roosevelt and his two Native wives. Teddy's first wife was named Brown Head, and the second was See-the-Woman. According to Sand Hill Crane, after Roosevelt left western North Dakota, "he became a big man." He continued, "We never said anything about these women to anyone," and that's "the way the white men did then in the country."

There are predatory implications of how Anglo-American males behaved with the above examples, and this article doesn't even begin to scratch the social Darwinian thought processes intrinsic to the 19th century (for that, start with Richard Hofstadter's foundational work, “Social Darwinism in American Thought” [1944]). While these three cases -- Sully, Custer and Roosevelt -- deal with the real and possible, the campaign against cohabitation continued in the urban settlements.

Historians with North Dakota State University's "Fargo History Project" (http://fargohistory.com/) have unraveled the early tension between the laws on the books, and how and why those laws were not enforced in Fargo between 1889 to 1911. This too, no doubt, is a reflection of the early legislative desire to criminalize cohabitation.

Digital historian Chris Hummel noted that "eliminating prostitution was not as easy as changing a few laws," also citing the attempts at prohibition as another case in point. Within Fargo, Malvina Massey operated a brothel known as the "Crystal Palace," and this, according to historian and professor Caroll Engelhardt, was often visited by traveling salesmen and migrant laborers who tended to railroad construction and bonanza farming operations (perhaps the original "man camps") during planting and harvest seasons.

A tension developed between the business owners and city leaders, who often looked the other way, and the church leaders and moral reformers who sought to legislate and enforce morality. City leaders often tolerated prostitution, at least in certain amounts, and even developed an informal "tax" toward the established brothels. The "tax" was collected when law enforcement was told at particular times of the year to go and enforce the laws.

This -- having laws and having laws that are enforceable -- returns to a central theme as to how and why a cohabitation law came about in the 19th century, and how and why it was removed from North Dakota law in the early 21st century. Another point in removing the law, at least as Potter saw it, was to make sure that senior members of North Dakota would not be breaking a law if they decided to live with family or friends in the latter years of their life.

The history of this particular law is a sample of how proposed measures, and laws, have deeper implications than what is on the ballots during election day. It is up to each voter, too, to research and consider the implications of individual measures and each legislator they are considering voting for.

It takes time, of course, and to a degree it reminds me of a Winston Churchill quote: "It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried." Churchill, using wry British wit, was speaking of the inefficiency of the democratic process, and at the same time complimenting that process.

In a nod to that inefficiency, I will be doing what I can to read up on the voting history of legislators, the measures proposed, and the historical processes that brought those measures about. It's on us to keep this democratic-republic moving forward. Happy voting day.

February 23rd 2026

February 16th 2026

February 13th 2026

January 15th 2026

January 15th 2026

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)