News | July 10th, 2019

WEST FARGO – March 2018 was an unusually cold and violent month for Fargo. Two standoffs – one of which ended in the death of Justin Dietrich – came days before police responded to Lance Belgarde’s former Horace home, a house he built with his own hands during his approximate 20-year marriage to Kimberly Belgarde.

February had fared little better across the valley. Across the frozen Red River a Minnesota State Patrol trooper shot Melody Gray after she attacked. A Clay County sheriff’s deputy wounded Brady Adrian after he stole a Taser from a deputy who used the shocking device on the deputy who then shot him. All of the incidents could be called precursors for the March 21 shooting of Orlanda Estrada, who threatened police with a knife in a South Fargo apartment before holding them at bay for approximately six hours, posting a live feed of his gunshot wound on Facebook.

In Belgarde’s case, the state aimed to prove an armed standoff ensued after he kicked down the door and made threats. Belgarde’s family and a former attorney say he wanted closure to a messy divorce and fell asleep, waking hours later to 27 police cars, a SWAT team, a Bearcat, and someone yelling in a megaphone saying they could see him through the window.

Kimberly Belgarde and another man in the house, Mark Olson, were not hurt during the “standoff.” Nobody shot at sheriff’s deputies during the alleged five-hour ordeal, according to police. His bail was set at $250,000, cash only. Defended by attorney David Dusek, but facing up to 10 years behind bars if he took his case to court and lost, Belgarde maintained his innocence until July 3, and then changed his plea. Family reports the plea arrangement includes up to five years imprisonment.

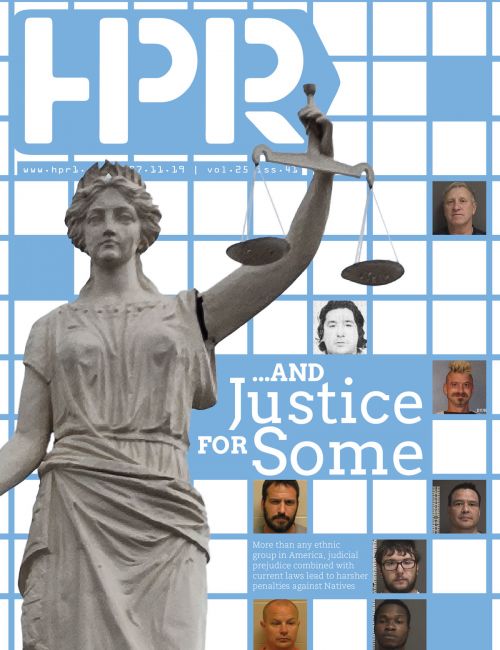

Whether or not the police response was adequate or too much or not enough, isn’t the question some people are looking to answer. Belgarde’s family and friends want to know why Belgarde was treated more harshly than his white counterparts. Why was his bail set at a quarter of a million dollars in March 2018? And why was the state seeking to put him behind bars for up to ten years if he went to trial when nearly a dozen others in recent years have seen little to no jail time for similar offenses?

Belgarde is Native American, from the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa. His criminal record is short, includes disorderly conduct and driving under the influence charges. At approximately 53 years old, Belgarde stands at six feet eight inches, and is quiet spoken; he could shame a bear with his handshake.

“He has no real criminal record, I know at the time I represented him they weren’t willing to make any reasonable deals,” William Kirschner, Belgarde’s former attorney, said. “The problem is the look of it and not what happened. I don’t know if he had a loaded gun or not. He got into treatment as far as I know, as far as I know he’s staying sober. If all of those things are true, he’s already suffered from representing himself during his divorce.”

His former wife, Kimberly Belgarde, appears to be well connected to the community and has been a grade school teacher with Fargo Public School for more than 20 years. She is listed as the camp director of YMCA of Cass and Clay Counties’ Camp Cormorant, and in 2012 and 2013 as the president of the Fargo Education Association.

According to Been Verified, a legitimate background check website, and confirmed by the Cass County State’s Attorney’s Office, Kimberly Belgarde of Horace, had two misdemeanor class A charges against her that were dismissed in the late 1990s. On June 20, 1998 a charge of assault was filed and later dismissed. On February 3, 1999 she was also charged with giving false report to a law enforcement officer, which was also dismissed.

Guilty or innocent, Belgarde’s chances in court suffered under systematic prejudice, Grand Forks attorney David Thompson said. Federal statistics validate Thompson’s claim.

“The prejudice is real,” Thompson said. “Native Americans characteristically in pre-trial, release, and sentencing situations often are unable to marshal the resources, and are less able to convince trial judges to treat them with forbearance and leniency.”

Prosecuting attorney Leah Viste said Belgarde’s case was unique in that the incident could have had a more terrifying ending.

“I’ll speak theoretically when I look at a case, the lethality of a case will play a role in how I look at it and what could have happened in that case had it not been for police intervention or something of that nature,” Viste said. “This one was a really – in my mind – a terrifying case. I felt like we would’ve very likely – had there not been police there – had a murder/suicide on our hands, that’s how it really felt to me.”

Marcy’s Law plays a role in how the state prosecutes a case, Viste said. Although she wasn’t bound to abide by what the victim, Belgarde’s former wife, wanted in this case, her office had to take her concerns under consideration.

“The only thing I have ever heard was that he has no memory of events, and voluntary intoxication isn’t a defense,” Viste said. “He wasn’t charged with attempted murder, which is an intentional crime, then that part would have been contemplated. The fact of the matter is all forms of people commit crimes. They can be the greatest people in the world and have one bad night. That doesn’t change that fact. It’s one of the more tragic cases because they’re a family and there are kids and that’s always awful.

“My job is to weigh this and look at it, and there are so many different ways to look at these types of cases. What do you need to do to get their attention? Do they recognize the seriousness of their crimes and how significantly it impacted the person? There are a number of things to look at and I’ve looked at all of those things. Would he commit another crime again? I don’t know, maybe he never would. One of the theories is that if you do something that’s bad enough you have to go to jail regardless of whether or not you ever commit a crime again.”

“He was intoxicated, but I don’t know if they ever run a blood alcohol on the guy,” Kirschner said. “Why didn’t they run a blood alcohol on this guy? My understanding is he woke up, and alcoholics have blackouts, but from what I can tell he never took any shots at anybody, he never stopped anybody from getting away, and he came out with his hands up.”

Doing time in prison should not be part of Belgarde’s plea arrangement, Kirschner said. He practiced law for nearly 40 years in the area before retiring.

“What you have here is a guy with a clean record, never threatened anybody before, never harmed anybody before, and he got treatment,” Kirschner said. “I don’t know how putting him in prison would serve anybody.

“I think the use of prison is overused in many places, and that’s why the North Dakota prisons have become increasingly overcrowded because we’re putting people in prison who don’t need to be there. That’s the issue. Why are all these people going to prison when that’s not what they need?”

Historically, the state’s treatment of Natives speaks for itself, contrasting starkly with sentences handed down to white residents.

Skipping centuries of broken treaties and hostility toward the Indigenous, Leonard Peltier, of Lakota and Dakota descent and an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, has been behind bars since 1977 after he was convicted of murder. A Fargo court sentenced Peltier to two consecutive life terms for his involvement with American Indian Movement’s resistance against the FBI on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation where two agents were killed.

Numerous appeals have been filed on Peltier’s behalf claiming his innocence. International personalities such as Nelson Mandela, the Reverend Jesse Jackson, the 14th Dalai Lama, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and others support him, saying he is a political prisoner. Until now, all petitions for clemency have been denied.

In one of the biggest criminal trials in state history, 11 Natives were found guilty of the hit-and-run murder of Police Officer Eddie Peltier in 1985 on the Devils Lake Sioux Reservation. Part Mexican, part Sioux, Richard LaFuente was arrested along with ten others for the crime, but they always maintained their innocence. Without physical evidence and even though all but one of the suspects had alibis, they were found guilty by the U.S. District Court in Fargo.

LaFuente received a life sentence, but was released in 2014 after 28 years behind bars. He consistently refused to acknowledge his guilt even when given the opportunity for release on multiple occasions. The real killers have never been found.

During the 2016 - 2017 Indigenous-led No DAPL controversy, 836 Natives and others were arrested with only 26 people convicted at trial during the fight against Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access Pipeline. At that time the state refused to listen to Native concerns as the pipeline crossed the Missouri River less than one mile away from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, and helped push the private project through. After pipeline completion, Dallas-based Energy Transfer Partners and subsidiaries paid in excess of $15 million to the state, $5 million to the University of Mary, and another $3 million to the City of Mandan.

Other cases in the past decade involving crimes similar to what Belgarde faces today were pleaded, and in most instances the suspects received no additional jail time. The cases appear to be primarily white men with varied criminal histories.

In 2017, Steven Gerald Sorenson from Harwood, was charged with three felonies that involved a standoff with police: felony terrorizing, reckless endangerment, and felonious restraint. According to police reports Sorenson fired six to seven shots during the standoff, but no one was hurt.

Sorenson’s bond was a promise to appear in court. He eventually pleaded guilty and was sentenced by Judge Susan Bailey to a fine of $525, time served and electronic home monitoring in lieu of jail time, and two years probation.

On October 29, 2017, Ryan Kitch, 21 and Oscar Kayee, 26 attempted to rob a man during a drug deal at West Acres. The burglary went wrong; a chase ensued. Shots were fired, but nobody was hurt. Kitch, the driver, was released on $10,000 bond, and later sentenced by Judge Frank Racek to 44 days in jail – time served – and Kayee was sentenced to six years, primarily due to an unrelated felony charge of sexual assault involving a 16-year-old, according to court records.

The Smith and Wesson used to pistol whip a victim was turned over to law enforcement.

In August 2017, Michael Skroch held Richland County police at bay for six hours after threatening someone with a sword. Police were finally able to arrest Skroch after using tear gas to enter the premises. Skroch pled guilty to reckless endangerment and was sentenced by Judge Bradley Cruff to two years supervised probation, credit for time served, and a fine of $535.

In February 2015, David Matthew Berg was found guilty of aggravated assault, burglary, and two counts of terrorizing and was released on $10,000 cash bond. Judge Herman Douglas sentenced him to two years jail time, two years probation, and a small fine.

Berg’s criminal record is filled with driving under the influence, issuing checks without funds, assaults, and a month after his release on bail, he was charged with criminal mischief, burglary, and aggravated assault, according to court records.

In November 2014, Dustin Hagman violated a protection order and threatened a woman with a handgun before surrendering after a standoff with police and SWAT. He later pleaded guilty under the Alford plea, which means he understood there was enough evidence to convict him, but did not admit guilt and was sentenced by Judge Steven Marquart to time served. Fines were waived.

In October 2014, Todd Romann Sandberg was involved in a standoff with Cass County sheriff’s deputies after shots were fired, resulting in felony charges of terrorizing. Judge Frank Racek sentenced him to work release, 120 days in jail, 18 months of probation, a fine of $525, and forfeiture of his weapon.

In June 2009, Scott Allen Moen pleaded guilty to felony burglary, terrorizing, interference with a telephone during an emergency, and simple domestic assault. Moen’s criminal record is long and primarily drug related. He served 87 days and was sentenced by Judge Georgia Dawson to six years with three years suspended sentence and five years probation, along with an $800 fine. Six years later, Moen was found guilty in the beating death of Joey Gaarsland, and was sentenced to 20 years in prison by Judge Susan Bailey.

In July 2009, Leonard Ritter was involved in a nine-hour standoff with Fargo police and fired live rounds at a SWAT robot that breached his apartment. He was charged with terrorizing, reckless endangerment, preventing arrest among other charges, and because of a mental condition, Ritter was sentenced by Judge Frank Racek to five years imprisonment with four years and 185 days suspended plus five years probation.

Statistics speak for themselves

Data on how Natives are treated in the judicial system show that on a federal level they receive harsher penalties for committing the same crimes that white people do. The same data, however, is missing from state courts. Race is not recorded or analyzed.

“I never had a judge indicate that they sentence people worse because of their race, but there is that bias in the community,” William Kirschner said. “Unfortunately that exists.”

The United States Sentencing Commission is a bipartisan and independent agency created by Congress in 1984 to reduce sentencing disparities while promoting transparency in sentencing. One of the agency’s jobs is to track sentencing statistics and reveal disparities when caught at the federal level.

Federal courts keep track of racial statistics in their data, allotting Natives to the “other” category.

Since the 1930s, racial disparities in the federal courts on sentencing have leveled between whites and blacks, but Hispanics represent 54.3 percent of those incarcerated with Native Americans 3.8 percent, according to statistics released by the US Sentencing Commission.

According to the United States Census Bureau, however, African Americans represent 13.4 percent of the population of America, with whites representing 76.5 percent. Native Americans represent 0.2 percent and Asians 5.9 percent of the total population.

In 2017, Native American offenders accounted for 2.4 percent of all federal offenders, with North Dakota reporting nearly one third of district caseloads were related to Native offenders. There are approximately 30,000 Natives representing five percent of the population in North Dakota.

Nationally, cases involving Natives represents approximately five percent of the overall federal caseload, but more than 80 percent of manslaughter cases and 60 percent of sexual abuse cases arise from Indigenous jurisdiction, according to a 2003 report investigated by the Native American Ad Hoc Advisory Group, which filed reports to Congress and to the United Nations Commission on Civil Rights.

“While Indian offenses amount to less than five percent of the overall federal caseload, they constitute a significant portion of the violent crime in federal court,” the advisory group reported.

A total of 89.5 percent of Native offenders across the country were sentenced to “within range” imprisonment with an average sentence of 45 months, which was 15 months less than the average sentence for all United States citizens. Despite the decrease, above range sentences for Native Americans – which are sentences that surpass standard ranges – have steadily increased from 5.8 percent since 2013 to 7.2 percent in 2017, according to the US Sentencing Commission.

More than a century after the implementation of the Major Crimes Act – which federalized six felony offenses involving Natives and fragmented Indigenous tribal government jurisdiction – an advisory group on Native American sentencing determined in 2003 that Natives were treated more harshly by the federal sentencing system than if they were prosecuted by their respective states.

Because of jurisdictional issues related to Indigenous reservations, cases involving Natives committing felonies on tribal lands are sent to federal courts rather than state courts. All felonies committed on tribal lands are the responsibility of the federal government; tribal courts try misdemeanors.

“Federal sentences for aggravated assault are indeed longer than state sentences,” the Native American Ad Hoc Advisory Group reported. “Because Native Americans are prosecuted federally for assaults, they receive longer sentences than their non-Native counterparts in court.

“Indians are more likely than any other ethnic group to be incarcerated federally for assault. While Indians represent less than two percent of the U.S. population, they represent about 34 percent of individuals in federal custody for assault.”

The problem stems from history and geography, and not necessarily racial animus, the advisory group reported. Regardless, disparity exists.

Testimonies heard during the Native American Ad Hoc Advisory Group also reflected that a perception exists that federal courts sentence Natives more harshly, especially when related to involuntary manslaughter and sexual abuse offenses.

“It is the jurisdictional framework that places more Native American offenders in federal court, and when coupled with the longer federal sentences, it results in a disparate impact on Native Americans,” the advisory group reported. “The perception among some Native Americans that they as a group receive harsher penalties for sexual abuse offenses than non-Native Americans is accurate.”

The group’s findings came out at the same time the PROTECT Act was enacted, which increased the disparate impact of federal sentences on Natives. The new law enacted the “two strikes you’re out” provision imposing mandatory life sentences on anyone convicted in federal court of a second sex crime in which a minor is a victim.

“Also troubling is the fact that Congress neither consulted with nor seems to have anticipated the consequences of the PROTECT Act on Native Americans,” the advisory group reported. “This silence suggests Congress has enacted legislation that will have a demonstrable impact on Native American offenders, already subject to greater sentences in federal courts, without having heard from those impacted nor giving any thought to that impact.”

Alcoholism plays a significant role in all violent crime coming from Native reservations, according to the advisory group. Addiction to alcohol contributed to “major changes in Indian life with erosion of traditional family networks, a change in parental roles and a growing sense of isolation and disconnection from the past.”

The effects of alcohol – historically introduced roughly two centuries ago – has caused severe and permanent family disintegration and chaos among Natives, according to the advisory group. The problems with alcoholism are compounded by the lack of resources to treat addictions.

Lack of proper resources trickle down to all areas of Natives living in urban areas, according to a study performed by Dr. Donna Grandbois and Dr. Ramona Danielson, public health program evaluator and research specialist for the Department of Public Health at NDSU. Without access to proper healthcare, financial stability, even transportation and language services, Natives feel targeted and are typically excluded from communities.

“American Indians in North Dakota have urgent unmet health needs, resulting in stark health disparities,” Danielson said in the 2012 study. “On average American Indians in North Dakota die 20 years younger than the white population (57.4 years compared to 77.4 years from 2007 to 2012). Nationally, American Indian health disparities cross a spectrum of issues including infant mortality, injuries, alcohol/tobacco use, chronic disease, addiction, and mental illness.”

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)