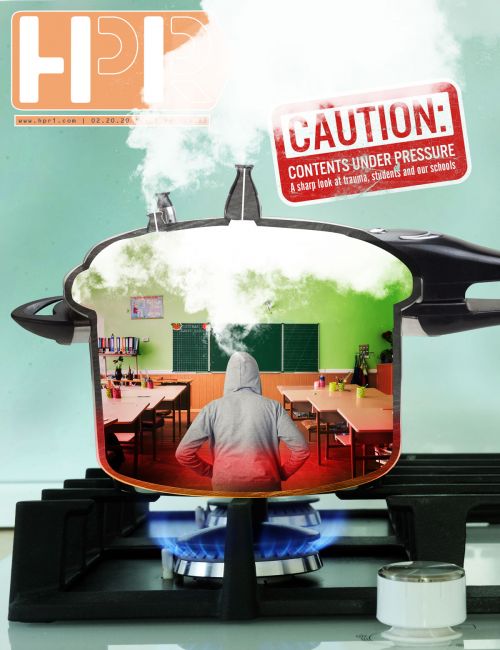

News | February 19th, 2020

by Meg Luther Lindholm

mlutherlindholm@gmail.com

Who was it that said that the health of a city can be measured by the health and well-being of its children? If no one else has made that claim – then I’m making it now. And to judge by the recent report on the state of Fargo’s public schools there are children whose emotional health is so poor that their behavior is undermining other students, teachers, staff and the social atmosphere in their schools.

I had no sense of this when I, as the parent of a Middle School student, joined the almost full-to-capacity crowd at Fargo South to listen to Superintendent Dr. Rupak Gandhi deliver his State of the Schools address on January 7th. Not having read the documents outlining the school district’s strategic priorities that were sent out beforehand I was simply looking forward to a feel-good dose of boosterism. After all aren’t speeches about the State of the Union, the State, the City or in this case the Schools an opportunity for the leader in charge to gloat over past achievements and future goals? Weren’t we there to be serenaded with talk of strategic initiatives and operational plans?

Certainly, Governor Burgum in his recent State of the State address spoke glowingly of North Dakota’s great potential using words like “strong, and boundless opportunity.” But If he had sat in the darkened auditorium listening to Dr. Gandhi, he would have heard a very different message – one focused on the need to collectively address the traumas children are experiencing at home that can result in behavioral problems at school. And like a virus that infects the air we breathe, these problems can affect everyone around them including teachers, staff and other students. What is needed according to Dr Gandhi and the people I interviewed after his address is the training and resources to equip schools to become trauma sensitive - where teachers and staff understand the reasons for students’ acting out behavior and can respond in positive rather than punitive ways.

Role of trauma in children’s lives

Laura Sokolofsky grew up in Fargo and has been a counselor at Jefferson Elementary for sixteen years. While she has always helped students with behavior problems, she’s witnessed a marked increase in negative behavior over the last few years. “In the last 5 to 6 years we’ve seen an uptick in very disruptive, explosive, hurting behavior. There’s no single reason why. It’s very complex. There is more addiction, much more technology/screen use and therefore less involved parenting of children. The rising cost of things also makes it harder for people to meet the basic needs of children. You can’t make it on a minimum wage job.”

And while Dr. Gandhi says that children’s behavior problems cut across the boundaries of race and class it’s clear that economic pressures weigh heavily on many families. Thirty percent of the school district’s eleven thousand children qualify for free or reduced lunches. In fact, two elementary schools have such high numbers of low-income children that lunch is now provided free of charge to every student. A Regional Workforce Study prepared for several area agencies concluded that the fastest growing sector of the area’s economy was and would continue to be low wage jobs.

Last April Neel Kashkari, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis whose oversight includes both North Dakota and Minnesota spoke to business leaders and students at NDSU about the many job openings in the area. He said that Fargo’s employers will have no problem attracting workers if they raise their wages. “All these businesses say, ‘we can’t find workers,’ and I say are you raising wages? And they say ‘no.’ And I say well, then you’re just whining.”

The viral effect of trauma

Jenifer Mastrud is a teacher at Carl Ben Eielson Middle School and the President of the Fargo Education Association, the union that represents Fargo’s teachers and staff. She says that the kids experiencing trauma can have a strong influence on other kids. “There are kids who have never seen violence, never heard swearing and now they’re exposed to it in our buildings.” And like a virus, the behavior can spread. “there’s a gantlet of kids you have to pass in the hallways, with pockets of negative kids you have to get through to make it through the day. We find that some kids start to build a culture of negativity around them.”

Mastrud says her son, who was a junior at Fargo North High last year, was very concerned about the social atmosphere at his school. “He would talk about the violence, disrespect and harassment that would take place at the school during the day. He was part of the student leadership group and they were struggling to figure out ways to engage that group in positive behavior. Most of the kids become desensitized, they put blinders on, and they just try to make it through their day without getting involved. But these disruptive kids take away from content, curriculum and learning – they hog the teachers time. The other kids have to figure out coping and survival skills.”

Alexis Mathias who works with children who struggle emotionally as a Positive Behavior Technician at Clara Barton says “some have it (the ability to cope) and some don’t. I have kids that wear noise cancelling headphones to cancel out the noise of the environment they’re in to try to survive due to the peers who are acting out in their room.”

Trauma in the classroom

Teachers are also affected by students who act out in their classes. “When a teacher has to stop teaching in order to focus on a student’s behavior and management of that behavior, that causes other kids to lag behind,” Mastrud says.

“Teachers were seeing kids who were being physical like pushing other children, pushing the teacher, biting and scratching the teacher. We’ve had minor incidents to major incidents where there were concussions and hospitalizations. We had a teacher at Jefferson elementary who actually had a heart attack due to physical violence from a student,” Mastrud says.

Last year almost 800 Fargo Public School teachers and staff filled out a survey on safety in the schools. Almost 70 percent reported that they had felt intimidated by or fearful of a student(s) in the last three years. Almost 50 percent said that they had been hurt physically or mentally by a student(s).” And the large majority of respondents said they did not feel their schools had consistent policies for handling student abuse.

Upon starting his job as School Superintendent in the spring of 2018 Dr. Gandhi began hosting listening sessions with teachers and staff to learn about their concerns. After hearing many stories about aggressive student behavior, he and leaders of the Fargo Education Association established a safety committee “where we’re working together to identify what approaches we can do to make sure staff feel supported and to meet the needs of students,” Gandhi says. The safety committee started developing a five-year plan to address all aspects of trauma-induced behavior problems and ways to improve the school experience for everyone.

Creating trauma sensitive schools

The good news is that there’s a lot of information about childhood trauma, trauma’s impact on the developing brain, and what works to help children. The Department of Public Instruction (DPI) has published a Trauma Sensitive School manual created by Heather Simonich, MA, LPC, that Schools Counselor Laura Sokolofsky uses to train teachers and other school staff. She says there are lots of ways to help kids who are emotionally struggling right in the classroom. For example, “taking deep breaths, and learning how to turn negative talk into more positive ways of thinking and self-talk. Mindfulness, stillness and visualizations can also help calm the mind.”

The district is also emphasizing restorative justice practices. Traditionally used in the criminal justice system, perpetrators and crime victims speak to each other and with a team of trained professionals about the repercussions of crimes and about restitution.

Superintendent Gandhi says restorative justice has a much broader definition in the schools. “Restorative practices happen well before an infraction even happens. It’s based on the premise that you’re building a community of trust in your classroom and in your school,” which loosely defined means helping children build their empathy skills.

“Why would you care about others’ feelings if no one cares about yours?” Sokolofsky says. She says building empathy within classrooms can be done in many ways like reading books, building feelings vocabulary, recognizing feelings on others’ faces and bringing students together in a circle to speak and listen to each other non-judgmentally or to problem-solve. “There’s a lot of proactive work so that when there’s an infraction you assess the level of hurt and what you need to do to repair damage that’s been done,” Gandhi says, rather than resorting to punitive measures like suspending kids from school. And empathy-building skills, once taught, can be woven throughout the school day.

Helping the hardest to reach children

Anyone who doubts the schools’ ability to help kids suffering from severe trauma need look no further than Kristie Mahar Ortiz’ classroom at Washington Elementary. Her class is called a self-contained classroom because it holds and helps kids who are suffering so much that they cannot function in regular classrooms. “We’re not addressing the trauma, we’re addressing the reactionary behavior that happens as a result. If they’re going to have a meltdown or blow-up they can be safe,” Ortiz says.

Being safe can mean physically venting their anger by hitting a pillow or screaming into it. Or running laps around the hallways with staff on hand to make sure no one gets injured. “Their bodies feel better when they get it out,” Ortiz says.

Once the energy is released children can better learn how to manage their emotions. “For example,” Ortiz says, “if the child is feeling out of control they learn to stop and think. I tell them to take a breath. I say think about what you’re going to do.” In other words, “If I do something hurtful or aggressive or threatening, how will others feel? We sit as a group and talk about coping skills.” Each child also has a card with a list of their own chosen coping skills taped to their desk. “Building trauma sensitive schools also means teaching kids how to choose people they can trust.”

And when one child hurts another they learn how to be accountable. "For example,” Ortiz says, “if they have trashed a room, they have to clean it. If they’ve broken something, they fix it. If they hurt a person they apologize and myself, my paras and the principal will work with them. If another student has been hurt, we talk to that student and then we bring them together. The student who has hurt someone will write an apology and practice with a teacher and then present it to the other child in the whole group.”

“So many times, they (the students) have come to us having burned so many bridges, they have hurt so many, but this practice allows them to feel that they can still make friends, they can mess up and come back, like a family. They learn that they’re not throw-away kids, they have value.”

“Does it happen in three months? No. Six months? A little. After nine months it’s getting better. It’s a process. Not all tools work. They have to find the tools that work for them,” Ortiz says. The end goal is to help students regulate their emotions enough that they can move back into mainstream classes.

Ortiz says helping kids learn to be accountable for their behavior comes as a reflex – something that was part of her upbringing. “Coming from the Midwest, if you broke it you fixed it and that was the approach that I’ve always used. It didn’t have a name restorative justice at that time. I didn’t know what it was called. It was just being accountable.”

But, Ortiz cautions, the chances of success are much greater when families are involved.

“I text my parents every day to tell them what I’m discussing with the kids. I might tell a parent that their child needs to write an apology, so the child knows we’re a team – they won’t play a parent against the school.” And it also helps make the parents more accountable. “It gives the family ownership in the child’s behavior rather than them putting the blame on the school. In a trauma sensitive school, you can’t teach just the child, the family has to be part of the process.”

Not everyone in the school system connects with the idea of creating trauma sensitive schools. Some teachers feel overwhelmed with their already demanding jobs. Fitting in trauma sensitivity training and learning techniques to help kids with their emotions feels like an additional burden. But Sokolofsky says once everyone in a school receives training on how to help kids manage their emotions there will be more avenues of support available for all.

Jenifer Mastrud agrees. “I think the direction this is going in is what the teachers have been asking for for four or five years. We’re excited to see it come to fruition. We use the word ‘care’ and what that means to me is listening. When we hear the superintendent say ‘we care’ it means that he’s listening and taking action. We’re elated to have a cabinet that wants to take this on and work with teachers to create the best environment for all students.”

Alexis Mathias also agrees. “I think we’re finally going in the right direction with people who want to listen and help in our district office.”

When asked her opinion about the district’s focus on turning every school into a trauma sensitive school Laura Sokolofsky summed up her reaction in one word. “Finally!”

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)