News | August 22nd, 2018

by Elyssa McCulloch

elyssa.McCulloch@uj.edu

If you have looked at a newspaper or talked to a group of farmers lately you may have heard the news about pollinators, honeybees especially. With the increase of agricultural land and the consequent loss of native plant life, pollinators have been having a hard time. Annual loss of honeybee colonies is now greater than 30 percent, and many native bee species are in decline. However with the awareness of the issue being raised, actions have been taken to save the bees before it is too late.

Farmers have been agreeing to set aside small plots of unproductive farmland to grow a special concoction of wildflowers in order to help the bees attain all the nutrients they need to have healthy, happy hives – along with other measures to help sustain the environment. In the wake of all of this honeybee business there has been another pollinator struggling recently, the monarch.

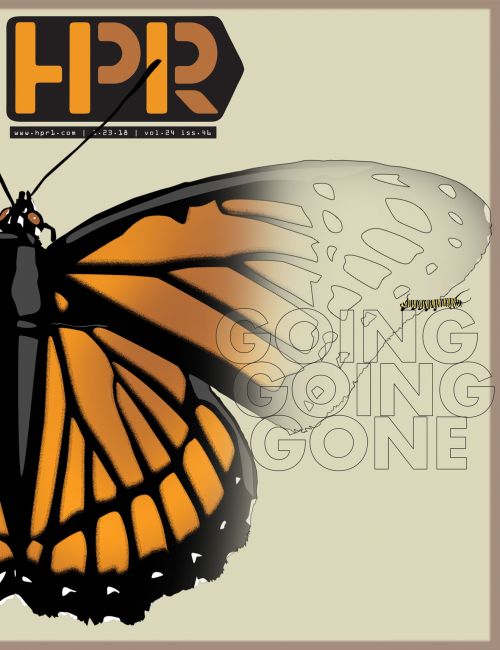

This iconic butterfly species suffered a decline of its own and has been under scrutiny by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Since 2014, the monarch has been proposed for listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and conservation efforts have been put into action to prevent this, pending an official decision that will be made in the summer of 2019.

The biggest threat to monarchs is the same as the threat to most pollinators – habitat loss. Deforestation and forest thinning in overwintering areas, and loss of milkweed host plants and pesticide use in summer breeding areas is taking its toll. The size of the Eastern North American population can be estimated by the size of the population that collects at overwintering sites in central Mexico. Monarchs migrate south each fall and roost on oyamel fir trees at 12 different sites in Mexico. Scientists do a population count by measuring the area of trees that are covered in orange clusters.

There has been a steady decline in these numbers since the 1990’s when the population was estimated at nearly one-billion. Now the population is estimated at about 93 million, but in order for the monarchs to have a sustainable population through their long migration, scientists suggest that these numbers need to be at least 225 million.

Other efforts have been made to monitor monarch populations during other stages of their annual life cycle. The Monarch Larva Monitoring Project, (MLMP), is a citizen science project that relies on volunteers who gather data on monarch larva abundance throughout the summer breeding range. They search for monarch eggs and caterpillars on their only source of food, the milkweed plant, and collect data that is pooled in an online database and analyzed by researchers from the University of Minnesota.

Training information and results are available on their website (monarchlab.org), which allows citizen contributions from all over North America. This is particularly helpful in understanding the percentage of monarchs that are coming from each area of their habitat.

With the pending decision of the monarch’s official status on the endangered species list comes a few complications. As mentioned, the monarch depends on one plant for its breeding season – the milkweed. This plant provides habitat and food for the caterpillar throughout its entire larval stage, and is a defense mechanism for it as well.

The caterpillar ingests toxins from the milkweed that do not harm it, but will make it toxic to potential predators, and this trait passes on to the monarch butterfly (hence its bright orange warning coloration!). Thus, the fate of monarch butterflies is intimately linked with milkweed. In order to help, some people have been planting a few milkweeds of their own right in their backyards! If the monarch is listed under the ESA, it is unclear whether additional regulations or protections may also be placed on milkweed.

Destruction or removal of a protected plant could result in expensive fines and that is a risk that many people may not be willing to take. Also, milkweed thrives in roadside ditches and on the edge of farmer’s fields, and if the farmers are not allowed to control milkweed then this could cause issues during harvest season as the milkweed could spread into their crops.

Harvesting milkweed along with their crops causes contamination of their product and can reduce their yield. These are just a few reasons why it has become critical to help monarch populations return to safe numbers and keep them off the endangered species list. This is where the MLMP data provides critical information - understanding exactly where the milkweed plant needs to be distributed can reduce encroaching on crop land where it is not needed, and help the monarchs where the populations are most abundant.

Some people have asked me, why is the monarch so important? The fact is that it isn’t about this species alone. The monarch is considered an umbrella species-meaning conservation actions designed to protect it also protects many other species that require similar habitats. This is one of the only butterflies that is able to be identified down to species by most people, and so it is easier to draw attention to the loss of this organism.

If we can improve monarch populations and maintain their environment then we will consequently be protecting anything else that resides in that habitat which just so happens to cover almost all of the Continental United States, ranging through Central America and down into the northern part of South America. Along with this, we can’t forget that monarchs provide a pollination service to farmers as well.

In an effort to encourage the integration of milkweed into new habitat plantings, I have also been participating in a study monitoring the abundance of milkweed in different seed mixtures made for pollinators.

The research is being done mainly at controlled plots at the Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center outside of Jamestown, North Dakota, with additional milkweed counts from participating farmer’s fields in other areas of North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota. This is being done in conjunction with native bee and honeybee research in order to determine the best seed mixtures for monarchs, native bees, and honeybees, allowing us the most efficient use of our conservation land for pollinators.

With the rise in awareness and conservation efforts, monarch populations has been recovering in the past few years, but it is still nowhere close to where it used to be. Continued conservation efforts by citizens could be the answer to this problem, but with the official decision on the monarch listing status coming out in the summer of 2019, only time will tell where this road is headed.

YOU SHOULD KNOW:

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)