News | March 28th, 2018

FARGO – Justin Lee Dietrich was an addict. A long rap sheet haunted him, barring him from joining a society that rejected him at every turn. Court documents show he had issues with sobriety, was ordered by Cass County District Court to attend sobriety programs, chemical dependency evaluations, and given two years supervised probation, after he pled guilty to terrorizing charges in 2016.

FARGO – Justin Lee Dietrich was an addict. A long rap sheet haunted him, barring him from joining a society that rejected him at every turn. Court documents show he had issues with sobriety, was ordered by Cass County District Court to attend sobriety programs, chemical dependency evaluations, and given two years supervised probation, after he pled guilty to terrorizing charges in 2016.

Before four Fargo Police SWAT shooters took the 32-year-old man’s life on March 12 for posing an “imminent deadly threat,” in West Fargo, he asked to live in F5 Project housing, but the nonprofit organization that coordinates services and living spaces for released felons had no beds available, a Facebook post by the organization’s founder, Adam Martin, stated.

His family tried to get Dietrich committed but he was turned down every time, as he didn’t meet the “danger to himself or others” standard.

“I think about all the times police were called, how the officers with Fargo PD were patient with him when it would have been far easier to do otherwise, but also how hiring the right defense attorney can repeatedly help a person avoid any real consequences,” Matthew Bring, Dietrich’s brother-in-law, wrote in a Facebook post.

“I think about how he’s been on probation with little or no actual supervision or oversight, and about the arrest warrant that was issued more than three months ago but never served. It’s frustrating, thinking about this broken system in which his family try so hard to get help from the very institutions set up to do so, and are repeatedly told there’s nothing more that can be done.”

Dietrich’s sister, Alyson Jean Bring, emphasized that she and her family tried repeatedly to seek help for her brother.

“My family filed numerous civil commitments in an effort to get Justin help and every time we were told by Southeast Human Services that he didn’t meet the legal standard of being a danger to himself or others,” Bring said in an email. “At one point I was literally told that we wouldn’t be able to commit him unless he was found with a gun in his hand and threatening to take his own life.”

Southeast Human Services personnel took 15 minutes to interview her brother, but would not consider her family’s extensive knowledge of his usage history, she said.

Bring, a former attorney with the Cass County State’s Attorney’s Office, said her brother was supposed to be supervised, but found little oversight. When the courts ordered Dietrich to go through treatment, the stays were too short. Counselors continuously had to justify treatment procedures to insurance companies, Bring said.

“In sum, the very institutions that are set up to help people are not working.”

Dietrich loved motorcycles and his pet, a Rottweiler named Harley. He had a beautiful singing voice, once sang at the North Dakota Adult and Teen Challenge approximately a decade ago. Friends and family said he was humorous, had an infectious smile, someone who went out of his way to make people feel important.

Once, he saved a neighbor from hanging himself. He cut down the rope, took the person to get food and groceries, and saved the person from suicide.

“It’s no secret that Justin was an addict and struggled with this disease for many years,” Bring wrote in her brother’s eulogy. “But I think it’s important to stress that each one of us has issues and our issues don’t define us. Addiction was merely part of his life.”

Bring also works as an attorney handling DUI cases, never before realizing how widespread addiction and alcoholism in the area are, affecting people from all walks of life.

“I don’t think the public at large realizes how big of an issue this is and that most of the people who enter the criminal justice system are either chemically dependent, mentally ill, or both,” Bring said.

Her brother was someone who helped whenever and however he could, Bring said, and she hopes to honor his memory by testifying at the next legislative session to try and implement positive changes for those struggling with addiction.

"I think the frustrating part for me is that, while everyone has issues, for some reason addiction is so incredibly stigmatized, and I think a big part of that is because, while it’s easy for people to hide most issues, typically addiction eventually can’t be hidden and becomes public,” Bring said in an email. “I think our society has made some strides in viewing addiction as a disease just like other mental health or physical problems, but I think we still have a long ways to go.”

Adam Martin

The name, F5 Project, is a double entendre. It stands for the reset function key, but also because Adam Martin has five felonies on his record.

“I’m not a mental health professional, I’m just a guy who has a bunch of felonies who is an addict, that found a solution that works,” Martin, founder of the F5 Project, said from his office. Feet propped up on his desk, he’s the picture of calm in a turbulent world. His office is behind the only white frame among a dozen hard oak antique doors on the eighth floor of the Black Building.

Although the F5 Project is barely two years young, he’s grown the organization from nothing to seven houses that help put roofs over felons’ heads. His organization’s goal is to lower recidivism and homelessness rates through education. Martin calls his organization the “anti-disenfranchised movement” because he breaks all the social rules: answers the cell phone at 2am, is active with those under his care on social media, and goes to inmates before they’re released to find out what they want.

Martin knew Dietrich, called him a “super awesome dude.” Dietrich was someone that Martin enjoyed, and not the person the media has painted. Current Fargo city codes was one of the reasons why Dietrich was turned away shortly before he was gunned down after failing to comply with police demands.

In Fargo, a house or unit is allowed to hold three non-related people, no matter how many rooms are in the house.

“It’s an archaic code that robs many of opportunity,” Martin said. Because of a previous infraction of the city codes, city leaders and others have called him a slumlord. He’s facing potential fines. Some ask him why college students are able to get away with breaking the same city code, while he, housing felons, cannot.

“My argument for that or my belief on that is I’m not mad that the college students are getting away with it, I think they should,” Martin said. “I think there is a big problem with housing in this community and it affects people with backgrounds and it affects college students. What does that tell me? It affects people below the poverty line.”

A legislative incentive passed in 2017 offering landlords the chance to collect double security deposits for felons looking for a place to live, is about the only help the state has given. The law, introduced as House Bill 1220 by the House Political Subdivision Committee, overlooks a crucial factor.

“They totally missed the boat on what the real problem is,” Martin said. “It’s not just the felony background, the majority of people coming out of jails or prisons don’t have money. Again, we’re creating opportunity for people with money.”

Money is the largest contributing factor in attracting the help people really need, Martin said. Proper funding is also the dividing factor between nonprofits such as the F5 Project and others as they’re all chasing the same donations and grants.

Money – billions, if not trillions of taxpayer dollars – is also being wasted every year keeping felons in a rut from which they cannot climb out.

Frank Hunkler

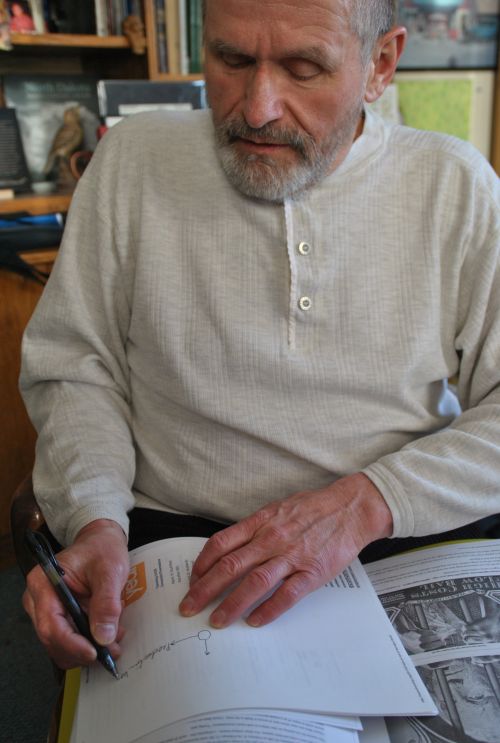

Dressed in corduroys, armed with a Pilot G-2 fine-point pen and a thick notebook of data, Frank Hunkler paused before speaking about the day he decided to commit suicide.

He’s a decorated Vietnam War veteran, a felon, an addict, has had PTSD since childhood, suffers from Asperger’s Syndrome, and has been a full-time volunteer peer mentor in the Fargo-Moorhead area for 37 years. He includes himself as one of the 256,934 reported civilian non-institutional people in America who were told they cannot work if they wanted access to health care including mental health. At a minimum of $10 an hour, that’s more than $5 billion in lost wages, and approximately $900 million in lost federal taxes every year.

He knows about addiction, started using drugs in high school and went to prison in 1979, back in the day when felons paid their dues, but were welcomed back to society after finishing their sentences.

“It’s harder to get clean and stay clean today than it was in 1980 or 1990, much more difficult,” Hunkler said.

Why?

“Access and prejudice,” Hunkler said. “In 1980 we did our crimes we did our time, we did our crimes and did our time. In 1980, very few people went to jail for drugs, almost unheard of.”

The war on drugs and the war on terror are pieces to the puzzle behind mass incarceration, Hunkler believes. America has five percent of the world’s population with 25 percent of the world’s prison population, and the hours of lost work, lost taxpayer dollars, and lost productivity, add up.

Nationally, the number of people enrolled in drug treatment programs has halved in recent years, although the demand for mental health treatment continues to rise, according to the Bureau of Prisons. Budget cuts to support the war on drugs and the war on terror, coupled with widespread disregard and an automation of human services have left addicts, felons, and the needy, forgotten.

Among comparable countries, America has the highest rate of death from mental health and substance abuse disorders. The number is almost off the charts, according to the Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker, with America double the rest of the world in death rates per 100,0000 people in 2015.

America’s death rates due to accidental poisonings or drug overdoses per 100,000 people is also twice as high as the worldwide average, numbering 12 people per 100,000 in 2013, compared to 4.9 per 100,000 in comparable countries.

Stress is the common denominator linking addiction, the current criminal justice system, recidivism, or the habitual relapse into crime or antisocial behavior patterns, Hunkler said.

“The process of seeking help, in preventive ways, is not in vogue,” Hunkler said. “The inhumane and failure-inducing requirements of seeking help in an emergency take a simple medical emergency to a personal catastrophe in which stress levels are exponentially raised.”

Although Hunkler has been clean for 37 years, his PTSD could bring him to suicide. Returning to drug use is not an option, he said. Suicide would be the only choice.

“With PTSD it could happen easily, not today, but over a period of months,” Hunkler said. “Right at that edge where life-or-death decisions are made every day by persons with use, abuse, mental health, addiction issues. I believe anyone who has even short-term struggles with mental health, use, abuse, and addiction issues has symptoms of PTSD. Often less from the struggles than from the lack of 24/7 access to emergency facilities and safety from themselves and others, forcing them to return to the situations that are killing them. Each refusal of care is another traumatizing event.”

His PTSD stems from childhood abuse, he said. He remembers little of his war experience, but has the medals to prove he fought with valor. As a gay man who lost 52 of his friends during the AIDS epidemic, his battle has been even more difficult than others, but he draws and writes almost every day to remind himself that people are basically good, and he must help them.

On social media, he begins all his posts with three simple words: “I love you.”

Remembering the day in 2003 when he decided to commit suicide didn’t come easily. While walking home, and passing in front of the offices of Minnesota Legal Services, after the Fargo VA refused help one last time, the director came running toward him. Hunkler said the director must have noticed that all was not well with him at the time. He was trying to get help, but insurance premiums and deductibles were out of reach. Medical bills, lawyer bills, were eating up his income.

“I was not depressed, I was freaked out by the world,” Hunkler said. “Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome is progressive and fatal. I had been clean from drug use since 1980. Using was not an option. Suicide held the only dignity I knew.”

The director of Minnesota Legal Services pulled him into the entry of the building and asked him why he was not on disability, Hunkler said.

“No one had ever asked me that. I said because I could not afford the expensive tests needed to find out if I had any real problems. I could not afford insurance and the VA had just told me they would not serve me under any circumstances. I had too many confrontations with staff over being refused help. I was a security risk to myself and the facility.

“She told me they would help me get help. I had to promise to quit work and promise to not work again ever, get completely destitute by a certain date to qualify for services, and 300 hours of their help later I was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome, PTSD, learning disabilities, and was given Social Security disability and a permanent VA disability pension.

$1.015 trillion: a drop in the judicial bucket

“Since I got on disability I have 29,000 and some hours that are lost,” Hunkler said. “Taxpayers have paid me over $500,000 in 14 years in monthly checks. I get a check every month, but that doesn’t mean I got medical health. I was under this crazy notion that if you’re on social security disability you get medical help. I was given a disability pension and then told to go away. I assumed that meant I got psychiatric help, but there is no such connection.

“How do you describe this to people that not only are they paying me to leave the work force, just to get medical help, I don’t know if you know this but when veterans get a disability check – it was not created to give us medical help. It’s basically a lawsuit, where each veteran is expected to get a million bucks. Congress did not mean this to be like Social Security disability to keep us alive, it was meant to replace the money we would likely lose in our lifetime.”

Hunkler is a part of the aggregate economic burden of incarceration to taxpayers, which exceeds $1 trillion every year, according to Advancing Justice, a Los Angeles based nonprofit and civil rights organization, and the Institute for Advancing Justice Research and Innovation, at Washington University in St. Louis.

Costs to corrections are approximately $91 billion, and lost wages – calculated at minimum wage – add up to more than $70 billion every year.

Reduced life earnings of those behind bars total more than $230 billion, while costs of non-fatal injuries to the incarcerated total $28 billion.

The aggregate cost to society swells from there, which including other aspects already adds up to more than $490 billion. Felons have adverse health effects from incarceration and poor health care. Infant mortality rates increase. There are divorce complications. Children’s educational level decreases, thereby lowering wages when they become adults. Child welfare costs go up; homelessness increases. There are increased criminality issues with children of incarcerated parents. Property values in troublesome areas decrease. Divorce rates rise, and the interest on judicial debt inflates.

In total, the cost per year for the current criminal justice system backing the war on drugs, the war on terror, and the current judicial system is $1,015,000,000,000, most of which is taxpayer dollars, according to statistics released by Advancing Justice.

“Expenditures are not adding value to the economy and are not, for the most part, improving the productivity of the incarcerated person and their families or adding value to the quality of life in the community for generations to come,” Hunkler said.

The costs do not end there. In 2018, the federal and state budgets for incarceration, probation, and parole is $80.7 billion. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, declared more than $50 billion. The Department of Health and Human Services, or HSS, announced $80.03 billion, and the Department of Education needs $59 billion.

Although numbers have decreased slightly in recent years, an average of 2.2 million people are behind bars on any given day, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics. If 2.2 million people had minimum wage jobs at 40 hours per week, 52 weeks per year, at an hourly rate of $10, the federal government loses more than $4.2 billion in taxes every year.

Wages earned by America’s total population of approximately 138 million taxpayers every year to pay for incarcerating 2.2 million people totals at $9.03 trillion, of which a total of $1.2 trillion is used to pay for the current incarceration system, according to Advancing Justice.

Additional unintended costs extend to more than half a million prison guards, who suffer from PTSD at more than double the rate of soldiers, and with suicide rates twice as high as the general public, according to analysts.

Simple numbers show the fiscal burden of incarceration is far more expensive than offering help to the millions of addicts sent into jails across America. The national average for treating one person in detox is $1,500, with an inpatient cost of $20,000 a month, according to the Center for Disease Control. For a fraction of the annual price to taxpayers, more than 11 million addicts – which is also the approximate number of people who enter jails in the United States every year, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation – could be treated for $375 billion.

Few jails offer addiction treatment services. At Cass County Jail, Captain Andrew Frobig is working toward alternatives to incarceration for low-bail offenders, but doesn’t have treatment services, yet, he said. Most help comes from the outside, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, the Sex Offender Program, the F5 Project, the group Hunkler works with, Narcotics Anonymous, or other nonprofit groups.

“It is very difficult to find anyone who claims, in 2018, that prisons and jails are for rehabilitation,” Hunkler said. “The inmates are not getting mental health help, are not being financially productive, are not learning skills, and the prison guards are losing out too.”

[Editor’s note: For more information pertaining to the criminal justice system in Fargo and North Dakota, a February 21 story pertaining to the “High costs of low bail” can be found here:link.]

Center for heroes and excellence

Frank Hunkler has a dream. His dream is to create a brick and mortar building, a one-stop 24/7 emergency center where anyone with a use, abuse, addiction, or mental health issue can go, keep safe from themselves and others, have all their emergency needs met, food to eat, a place to rest if needed, and given an advocate to get them connected to all the services they need.

“The community would guarantee to leave no one behind, get them the services they need, and find a way to pay for them,” Hunkler said. “Just like with heart disease, lung disease, type II Diabetes and other mostly preventable diseases. The commitment of the metropolitan area community would be to leave no one behind and provide the seamless services needed to return the person to maximum productivity as quickly as possible, no questions asked. To walk through the door and ask for help would make each person a community hero.

“By diverting funds, diverting facilities, ending the war on drugs, there is money enough, and the idea of this center in this town, number one, we need to have a campaign that encourages people to ask for help,” Hunkler said. “That’s the first problem, that’s probably 80 percent of the problem. Asking for help when they need it. That’s the heroism part.

“There’s no reason that anyone should have to use in this town, if we had access. There are enough treatment centers, homeless shelters, mutual aid agencies, if they had a central place where anyone could come to 24/7, I actually believe, right now as I know this community, there are days of the year where if we have that one center, existing facilities could serve every person who walks through that door without adding a bed.”

Fargo’s metropolitan area is smart enough and wealthy enough, Hunkler said, to become the first city in the world to help all our kids, felons, and addicts, and turn no one away.

Such a center would bring together all the agencies and services, voluntary and professional, Hunkler said.

“As each person is served, seamlessly and as a whole person, all agencies and services will benefit and maximize their potential,” Hunkler said. “At one time or another in our lives, we will likely all need those services unless we are wealthy enough or connected enough to get services we need when and where we want them. For now, only members of Congress and the very wealthiest have such access. A Medal of Honor winner cannot walk into a VA facility and demand services. A member of Congress can and does not have to demand them or stand in line for services.”

Adam Martin, of the F5 Project, compares the judicial system to the educational system, and finds that many of today’s issues start in schools.

“We have a whole social structure built on helping those who are convenient, and I think about that all the time,” Martin said. “We have this idea of what is not normal, and when something is not normal, we involve the police. Police have become more about arresting to create a culture than arresting to create public safety.”

Martin said he was in learning disability classes when he was in school in Fargo. The system is based on automation, and doing what is convenient.

“Let’s be open and honest about it,” Martin said. “Are you doing the same thing the educational system has done, and you’re sending people to learning disability classes because they’re inconvenient, they’re not normal, they’re not like other kids? Are you identifying them with learning disabilities because you suck as a teacher and you’re not actual teachers you’re reading out of a book? Or are you actually trying to create an environment to learn for all people. I think that kind of mentality has gone into the justice system, it’s gotten into even the technology world.

“All the systems in America are based on low hanging fruit. Nobody really wants to work.”

Rules on top of laws is not the answer to solving the current criminal justice system, Martin said.

“We’ve turned into a very legalistic nation,” Martin said. “If you’re familiar with the Bible and Pharisees and legalism, they were putting rules on top of laws and then holding people accountable as if it were a law, so that they wouldn’t actually break the law.”

Criminal justice reform is not ‘hug a thug’

While preparing for her nomination at the North Dakota Democratic-NPL Convention, Senator Heidi Heitkamp, who is up for reelection this year, said she would support criminal justice reform.

“On one condition,” Heitkamp said. “That we have re-entry services. And I will tell you why. I think that if you take someone out and you say ‘Okay, you’re serving time for a drug offense that didn’t jeopardize anyone’s life, you weren’t caught with guns,’ whatever the line is, I would say that’s fine, but you need to make sure they stay in treatment and that they have opportunities that help them transition their life back.

“If we don’t do it with that, we will have re-offenses, in fact I know that’s already happening in North Dakota, and that will frustrate law enforcement, it will frustrate the public, and it’s the wrong way to do it.”

Heitkamp stated she wants to know what reentry plans would include.

“When they come out of prison, how do they come back? They come back to the exact same conditions, and friends and associates that basically led to their incarceration. We need a reentry program for federal prisoners. This is one of the things that I’ve been pushing and doing a lot of work on.”

Former North Dakota Attorney General Tim Purdon said the criminal justice system is a three-legged stool: one leg is enforcement – some people are dangerous and need to be kept from society – a definition both Martin and Hunkler also agree with.

The second leg is crime prevention, and the third is reentry, Purdon said.

“Criminal justice reform is an issue that over the last three or four years – setting aside the current Attorney General – is something that has had large bipartisan support,” Purdon said. “There’s been a recognition in this country that we cannot afford to continue our criminal justice system on the road we’re on because the cost of running prisons, federal and locally, is exceeding our ability as a society to pay for it.”

He is a part of the Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration, and currently a partner with Robins Kaplan LLP, and said money can be redirected toward crime prevention and better delivery of mental health and addiction services.

“If you take the dollars that are being spent to warehouse people who have addiction and mental health problems, you take those dollars and redirect them at crime prevention programs that those people can get the chemical dependency treatment they need, they can get the mental health services they need,” Purdon said. “We are woefully behind a minimal constitutional standard for mental health care in the state of North Dakota.

“Look at the people coming out of prison and look at their recidivism rate. If you reduce that recidivism rate, give them a chance and integrate them back into society, you’ve reduced your crime rate.

“Reducing the recidivism rate isn’t hug a thug, this is making the community safer by making sure the folks coming back don’t reoffend.”

Concentrate on all three legs and incarceration rates will drop, he said.

Mandatory minimum sentences are one aspect of the current criminal justice system that needs change, Purdon said.

“Mandatory minimum sentences are a sledgehammer for every case, whether the case is an elephant or a gnat. We’ve got to get away from mandatory minimum sentences, particularly for people with addiction problems.”

The issue has become a hot topic today because the opioid crisis affects all levels of society, he said.

“The opioid crisis, unlike past drug crisis, hits populations in this country that have political power,” Purdon said. “Why are we talking about the opioid addiction as a national crisis as opposed to the crack epidemic? Why are we looking at it as a public safety issue instead of purely a criminal justice issue? It’s because its impacting communities that have some political power.

“It’s sad that that’s the case, but that is the case. There is a possibility that when you start to look at opioid addiction as a medical issue -- and all addiction should be viewed as a medical issue, in my opinion -- not necessarily a criminal justice issue but a health care medical issue, those folks need treatment, and hopefully that can support some of this recent bipartisan support for comprehensive criminal justice reform.”

Other states have begun taking dollars away from locking people up and putting funds toward treatment, and have reduced crime rates while reducing prison populations, Purdon said.

While mental health issues continue to be put on the political back burners, organizations like the F5 Project and volunteers like Frank Hunkler plan to continue struggling to find beds for the addicted, jobs for felons, words for the hurting.

“All that is lacking is people of goodwill putting partisan opinions and feelings aside and sitting as equals around a round table, with all stakeholders, and win this war on stigma and fear,” Hunkler said. “This fear of addiction and mental illness is based only in itself – fear.”

“It’s going to have to be a lot of awareness of the similarities between felons and non-felons, the similarities between the education system and the justice system, and how they’re treated, and the similarities between mom and dad approaches when it comes to people with felony backgrounds,” Adam Martin said. “When people see that and break the matrix in their minds, that’s when the help is really going to come.”

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)