News | June 13th, 2018

FARGO – He paced back and forth, arms crossed, fists clenched, at times stopping to peer out a 19th century window to the construction site below. An electric fan sucked warm, outside air providing short respite, if within arm’s reach.

Four steps right. Four steps left. His apartment is slightly larger than the federal prison barracks Nathan William Evenson was released from in February 2018, but at least the North Fargo place is his, and he is out from behind bars. The apartment is sparsely decorated. Two 35-pound dumbbells, a rowing machine, an old cavalry sword hangs from the wall, and a cabinet, painted in Norwegian Rosemaling, point to a reclusive, admittedly paranoid life.

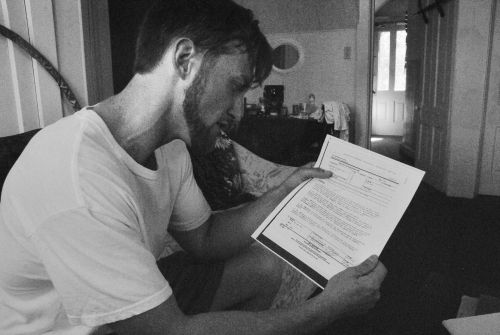

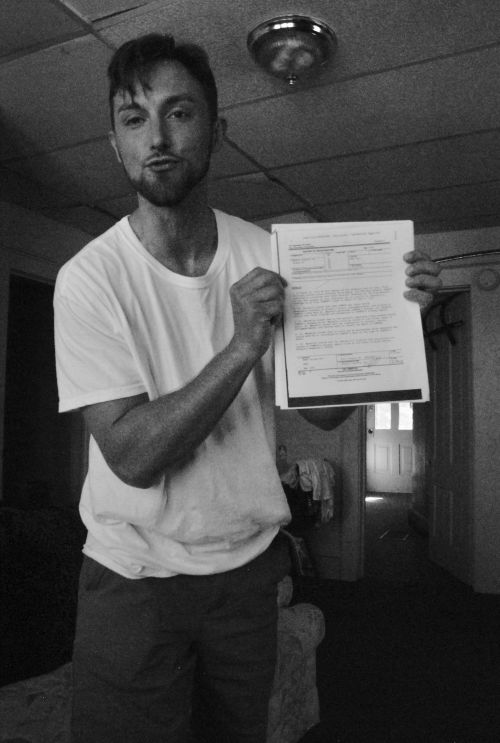

He stopped pacing, returned to a couch, shuffled through court documents until he found what he was looking for: a two-page report from the Department of Justice that he believes proves his innocence in the death of former Fargo blues guitarist Cody Dean Conner. It is a report that he, and the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Ralph R. Erickson, say he was never shown before he pleaded guilty to conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute and distribute a controlled substance in 2012.

“I don’t know why they did it,” Evenson, now 33, said. “But they ruined my life. They ruined my name in Fargo by saying I killed one of my friends. The record now reflects they withheld evidence.”

The record he never saw before pleading guilty was issued by the State Forensic Medical Examiner William Massello, which stated heroin was not the cause of Conner’s death.

“Dr. Massello stated that no one specific substance found present during Connor’s [Conner’s] autopsy by Dr. Massello could be stated as the factual cause of death,” the Department of Justice report stated. “Dr. Massello stated that the combination of alcohol, heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine more so caused the death of Conner.”

Faced with fighting the charge, which included a lifetime in prison and a $2 million fine if he lost, he eventually succumbed to prosecutorial demands. Written in the notes on the ensuing order granting motion to appoint counsel by Judge Ralph R. Erickson, Evenson wrote: “Signed plea agreement same day Gregor received email.”

Gregor, or Shannon M. Gregor of Nilles Law Firm, was the court-appointed attorney defending Evenson, who failed in her job to defend him properly by not alerting him to what became known as the Massello Report, Evenson said.

The two-page document took Evenson more than two years to find, and he found out about the report by accident.

“The reality of the situation was that it was a bunch of drug addicts shooting drugs,” Evenson said. “I feel really ashamed, like a social pariah, that people may think I killed this guy. Cody was a loved person and I loved him too. I don’t want a pity party, but it was terrible situation and I just want to be exonerated a little bit.”

He is contemplating a civil lawsuit, he said, because the US Attorney’s Office was wrong, and he can prove it. In the meantime he’s practicing guitar and working at painting houses. He wants to dispel the rumors that Conner was left for dead in a yard, or in a downtown back alley. He stayed with him, attempting CPR, until paramedics arrived. The incident police report confirms Evenson's account that he and Lund were trying to revive Conner when law enforcement arrived. Police discovered Conner's body by a tree in Evenson's front yard.

“He [Christopher Myers] circumvented a Supreme Court ruling to process innocent people and further his career,” Evenson said. “They viewed me as a disposable person at the time because I was a drug addict, but they basically took my life away. I was a bad person at the time, but I didn’t deserve to have my life taken away.”

‘Dancing with the devil’

Evenson is a self-described addict, and in 2012 he was a junkie, shooting heroin, smoking weed, meth, and popping pills before the price of prescription opioids skyrocketed. He even tried fentanyl before the synthetic drug became one of the nation’s most potent killers.

“It’s like dancing with the devil,” Evenson said. “You have to constantly do it [fentanyl]. It has no wheels on it, it doesn’t last.”

“It’s like dancing with the devil,” Evenson said. “You have to constantly do it [fentanyl]. It has no wheels on it, it doesn’t last.”

In 2012, he was with his friends and co-defendants, Nicole Wadsworth, and Seth Lund, when Conner, 30, came to Evenson’s apartment at 1437 16 1/2 Street South, asking for a fix, the incident police report stated. Wadsworth had found a gram of heroin, and they all shot it, Evenson said. His friend, Lund, shot the heroin into Conner’s arm, court documents reported.

“Cody came back and he was pleading, saying he was terminally ill with cancer,” Evenson said. “But Cody was scared of needles. Nicole gave him the drugs, and Seth shot him up with the heroin. I wasn’t a drug dealer; I was a drug addict.”

Evenson and Wadsworth then left, and came back an hour later to find Conner curled up on the floor hugging an oversized bottle of Everclear, he said.

Evenson and Wadsworth then left, and came back an hour later to find Conner curled up on the floor hugging an oversized bottle of Everclear, he said.

“He wouldn’t wake up, we moved him around for 20 minutes, trying to wake him up in the shower, and I feel ashamed to admit this now, we didn’t call an ambulance for 20 minutes.”No paramedics were called because most drug users are afraid of alerting the law, and because sometimes, when high, a person will pass out, or fall asleep and then suddenly wake up. Many of Evenson’s friends have died after overdosing, he said. To name a few a cousin died while inside a Fargo country bar, and Lund, Evenson’s co-defendant in Conner’s death, died in 2017 after he was released from prison, Evenson said.

Prosecution

The federal prosecution, led by then Assistant United States Attorney Christopher Myers, initially planned on October 10, 2012, to sentence Evenson to an enhancement, life imprisonment and a fine of $2 million, because he had a prior drug conviction involving cocaine.

In 2009, Evenson, 24 at the time, was sentenced to 18 months of hard labor under the Department of Corrections at Tompkins Rehabilitation and Corrections Center in Jamestown, but the sentence was suspended and he was placed under supervised probation for two years, according to court records.

Shannon M. Gregor, Evenson’s court-appointed attorney, repeatedly petitioned Evenson to change his initial not guilty plea to guilty, according to internal correspondence between Gregor and Evenson. The prosecution was determined to throw its full weight behind sentencing if the case went to court, and he faced a lifetime behind bars.

Originally charged with conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute and distribute a controlled substance resulting in death, the charge was reduced down to resulting in serious bodily injury, which requires much less verification for the prosecution to prove. He was indicted like a Mafioso, he said, by the federal government, when all he and his friends wanted to do was to get high. They took trips to Minneapolis to buy drugs, and sold them to each other, never making money off their deals.

He waited two years in county jails, postponing sentencing until judgment from a U.S. Supreme Court case in Marcus Andrew Burrage vs. United States.

The decision in the Supreme Court’s directly applied to his case, he said, which found Burrage not fully responsible for the overdose death of a person who had ingested multiple types of drugs, not the drug Burrage specifically supplied.

An autopsy report from the North Dakota Department of Health State Forensic Examiner showed Conner had multiple drugs and alcohol in his system.

Long after his co-defendants took plea agreements, Evenson accepted the government’s deal, and was sentenced to 12 years in a federal prison. He left county jail for Federal Prison Camp in Duluth, Minnesota, becoming prisoner No. 11836-059.

“I gave up hope,” Evenson said. “I didn’t want to die in prison. It was obvious that she [Gregor] didn’t want to go to trial, and I didn’t want to go to prison for life.”

Before pleading guilty, Evenson’s father, Brad, claims he was harassed by the US Attorney’s Office.

“He just called me up, and said that your son is going to go to jail for many, many years,” Brad Evenson said. “He said that I should still keep in touch with him, don’t disregard him, throw him by the wayside type deal. It was kind of like a harassment deal; it was uncalled for.”

In federal prison, Evenson spent the next few years avoiding fights, or facing fights head on, learning how to survive, and researching how to defend himself in legalese with the help of other prisoners. He didn’t file a motion to vacate or correct sentence until May 2016, after his recently-deceased friend Seth Lund was released from prison.

“I became my own lawyer,” Evenson said.

He found the medical examiner’s evaluation report by accident within his friend’s paperwork, after repeated attempts at discovery because his case was sealed by court order.

“Here Evenson was never provided the contents of the Massello Report, or even notified of its existence prior to his plea and sentencing hearing, despite the potential of the report to cast doubt on FAUSA Myer’s threat to take him to trial on charges that could result in mandatory life,” Judge Ralph R. Erickson said in his decision granting motion to appoint counsel for Evenson.

“There is no indication that anyone ever mentioned the report or its contents to Evenson after the hearing despite his many efforts to obtain information similar to that which was contained within the report.”

The Massello Report was missing from Evenson’s case file, Erickson said.

“Many of Evenson’s difficulties were related to the court’s protective order. When his counsel told him that he needed to seek permission of the court in order to acquire other items in his files, she did so because of the court’s order. This stringent protective order made Evenson’s ability to obtain or discover the Massello Report difficult, if not impossible. Evenson was an unrepresented prisoner with little legal knowledge, and even if he had made a request to the court at that time, the process may have extended past the deadline.”

Evenson’s 25-page motion to appeal was granted in October 2017. Erickson dismissed the indictment on February 9, 2018, despite a motion by the US Attorney’s Office to dismiss, and after Evenson spent five-and-a-half years in jails and prison.

When he was handed his release papers, he thought about staying in prison to fight, but life inside is a “nightmare,” he said. He’s free now, on probation, and clean, although he did test positive for alcohol on February 14, and on March 9, according to court records.

His release papers state his sentence was reduced from 144 months down to 51 months, but he served 65 months, and the basis for the change in status came from the Armed Career Criminal Act, a 1984 federal law that provides sentence enhancements for felons who commit crimes with firearms if they are convicted three or more times, and targets the special dangers created when an offender like a violent criminal or drug trafficker possesses a gun.

Evenson has never owned a gun, he said, nor did his charge reflect gun ownership.

On February 9, the day Evenson was released, Judge Erickson filed an amended judgment in a criminal case stating the indictment was dismissed. The same day the US Attorney’s Office stated, “in order to conserve scarce prosecutorial resources, promote judicial economy, and resolve all pending litigation in the case, the court should vacate the original sentence.”

In addition to three years supervised probation, Evenson is also being held responsible for paying $4,367.5 in restitution to Conner’s family.

Nicole Wadsworth, his co defendant, is still in prison, but she is scheduled for release this year.

‘Big Bad World’

Conner was the lead guitarist for the Moody River Band, a group still together after the tragedy and who recently released an album dedicated to Conner’s memory called “Big Bad World.”

Band manager and drummer, Corey Krueger, said Conner’s addiction shocked the band after his death.

“He did a really good job at keeping that part of his life away from us,” Krueger said.

Toward the end of his life, Conner was frequently withdrawn, and then suddenly would return to his old self, humorous and full of life.

“It was getting to be a tough thing by the time that he died,” Krueger said. “I know that he was never anything but great, and honest, and very self aware with me. If you say could I trust him, yeah I could. I never saw anything, even in the court of law, nope, never. Not one time. It took me a long time to believe it. It was like wow, unbelievable.

“Toward the end, the last few months, he was becoming undependable,” Krueger said.

Before he died, Conner had constant stomach pain, and Krueger also heard that his friend was battling cancer.

“Apparently that got him on pain killers to start with, and being an alcoholic, the doctors thought he was an alcoholic, and they couldn’t give him pain medications anymore, and that is when he went to other means.”

His death came before the opioid epidemic took regional headlines and became a national public health emergency claiming more than 64,000 lives in 2016. Approximately 175 Americans die every day from drug overdoses, and some predict opioid abuse will claim more than a million young people’s lives by 2020.

“It’s so sad, so many young people are dying,” Krueger said.

While in federal prison, Evenson said nearly every person he met had addiction issues. According to a June report made public by the Prison Policy Initiative, 698 people for every 100,000 residents are incarcerated in America. The United States leads the world for locking people up, and North Dakota – when compared to NATO nations – has taken the number one spot in the world for placing women behind bars with 155 people per 100,000.

Being addicted didn’t represent who Conner was as a person. He had addiction issues that most likely stemmed from prescribed medications, which forced him toward a heroin roller coaster.

“The best way to sum it up, if he had one dollar to his name, and if he saw a poor person here on the streets in Fargo, he would give that dollar away to someone less fortunate,” Krueger said.

Shannon Gregor and Christopher Myers were both contacted for comment, but neither replied.

[Information was added to this story after receiving the incident police report from the Fargo Police].

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)