News | January 26th, 2018

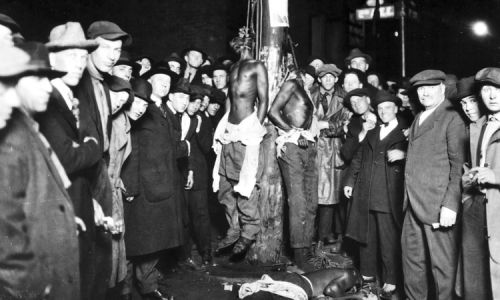

Editor's note: warning, this article includes graphic images some readers may find disturbing.

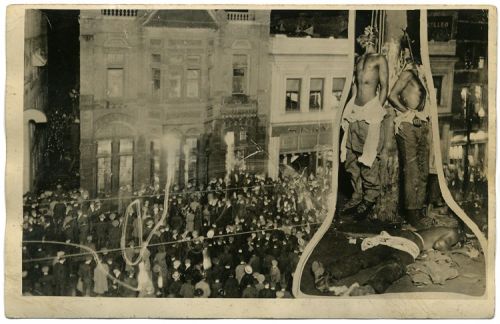

MOORHEAD, MINNESOTA – During the dark days after three African Americans were lynched by an angry mob in Duluth, Minnesota, a sepia-toned postcard was sold depicting the event. Two bodies against a lamppost, necks twisted away from the camera, ropes taught against their skin, dangled over a third body on the ground. In the postcard, the lynched men are cut out, pasted across a massive crowd attacking the Duluth Police Department.

MOORHEAD, MINNESOTA – During the dark days after three African Americans were lynched by an angry mob in Duluth, Minnesota, a sepia-toned postcard was sold depicting the event. Two bodies against a lamppost, necks twisted away from the camera, ropes taught against their skin, dangled over a third body on the ground. In the postcard, the lynched men are cut out, pasted across a massive crowd attacking the Duluth Police Department.

Faces aren’t clear in the postcard, but they’re smiling and wide-eyed in the original photograph. One ghostly-white face after another – overexposed by a flash lamp – dressed in fashionable suits, homburgs and newsboy hats, stand proudly moments after their victims – cotton shirts pulled down as handcuffs – have been brutally killed without a trial.

Despite 26 exposed faces, plainly visible, only three would stand trial on riot charges. The story and the photographs are difficult to palate. In the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan was on the rise across the United States, with chapters in Fargo, Valley City, Grand Forks, Duluth, and elsewhere in the two states. Anti-Semitism and hatred against Catholics were brewing; politicians needed someone to blame for economic downturns that would soon become known as the Great Depression.

During a warm spring night on June 14, 1920, the John Robinson Circus pitched its tents in Duluth. It was free, and attracted Irene Tusken, a white 19-year-old girl, a stenographer from West Duluth, and her date, James Sullivan, 18, a senior at Denfield High in West Duluth who worked as a boat spotter on the ore docks where his father was also night superintendent.

Reflecting limited facts discovered later in the trial, events that occurred after Tusken and Sullivan entered the rear of a tent at the circus are unknown, but later that night Sullivan reported to his father that six black circus workers held them at gunpoint and raped Tusken.

Despite the lack of evidence, only vague physical descriptions of the assailants, and a doctor’s examination report by Dr. David Graham, the family physician, declaring she had not been assaulted or raped, Tusken’s story incited a vengeful mob. Rumors that Tusken was dead or dying fueled the mobs’ hatred.

Despite the lack of evidence, only vague physical descriptions of the assailants, and a doctor’s examination report by Dr. David Graham, the family physician, declaring she had not been assaulted or raped, Tusken’s story incited a vengeful mob. Rumors that Tusken was dead or dying fueled the mobs’ hatred.

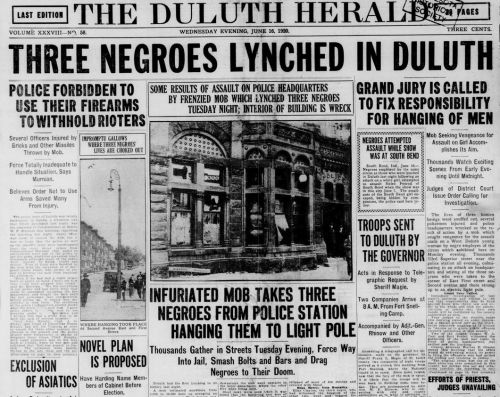

Duluth Police immediately arrested three circus workers: Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, all in their early 20s. Newspapers reported the incident, and word spread quickly as a Great Plains winter wind, inciting a mob of approximately 10,000 people to gather on Superior Street outside the Duluth City Jail.

Ordered not to use their guns by Duluth’s Commissioner of Public Safety, William F. Murnian, police offered little resistance. The mob threw bricks, and used rails, and heavy clubs to force a way into the jail. Police Sergeant Oscar Olson and Lieutenant Edward H. Barber were left in charge; their superiors, Chief John Murphy and Captain Anthony G. Fiskett, were chasing the circus 64 miles away to Virginia, Minnesota to arrest more suspects.

Ordered not to use their guns by Duluth’s Commissioner of Public Safety, William F. Murnian, police offered little resistance. The mob threw bricks, and used rails, and heavy clubs to force a way into the jail. Police Sergeant Oscar Olson and Lieutenant Edward H. Barber were left in charge; their superiors, Chief John Murphy and Captain Anthony G. Fiskett, were chasing the circus 64 miles away to Virginia, Minnesota to arrest more suspects.

With only a dozen officers left behind, they positioned themselves at the front and rear. Some police officers used clubs. Olson used a fire hose to blast the mob with water, and is reportedly the last officer to give up. Barber attempted to organize officers and retake the jail by force, but failed.

Heavily outnumbered, the police defense crumbled.

Inside, the mob tore doors off hinges, smashed windows, and took the three African American circus workers. A mock trial ensued, and all three men were declared guilty. They were taken one block away to a light pole on the corner of First Street and Second Avenue East where they were beaten, then lynched, first McGhie, then Jackson, and lastly Clayton.

Murphy, the police chief, arrested 10 more African Americans and returned to downtown Duluth after the first victim had been lynched.

The next morning the Minnesota National Guard arrived to protect three surviving African American prisoners, who were moved under heavy guard to the St. Louis County Jail. Resembling the racial cleansing of Forsyth County Georgia, black residents across the area stayed inside, locked their doors, afraid of progressive violence.

The next morning the Minnesota National Guard arrived to protect three surviving African American prisoners, who were moved under heavy guard to the St. Louis County Jail. Resembling the racial cleansing of Forsyth County Georgia, black residents across the area stayed inside, locked their doors, afraid of progressive violence.

Headlines across the United States expressed shock. The Chicago Evening Post wrote: “This is a crime of a Northern state, as black and ugly as any that has brought the South in disrepute. The Duluth authorities stand condemned in the eyes of the nation.”

The Minneapolis Journal accused the mob of “an effaceable stain on the name of Minnesota,” stating: “The sudden flaming up of racial passion, which is the reproach of the South, may also occur, as we now learn the bitterness of humiliation in Minnesota.”

Other newspapers, such as the Ely Miner defended the mob, saying: “While the thing was wrong in principle, it was most effective and those who were put out of their criminal existence by the mob will not assault any more young girls.” The Mankato Daily Free Press referred to the three men who were lynched as “beasts in human shape… Mad dogs are shot without ceremony. Beasts in human shape are entitled to but scant consideration. The law gives them by far too much of an advantage.”

Across the bay in Superior, Wisconsin, the acting police chief declared: “We are going to run all idle Negroes out of Superior and they’re going to stay out.”

All African Americans employed by the carnival in Superior were fired and told to leave the city.

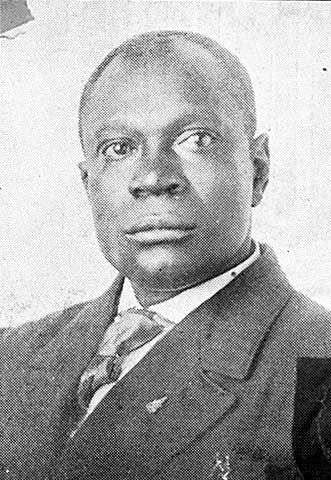

A total of thirteen African Americans were arrested in relation to the alleged rape, seven men were indicted, and two were tried, according to the Minnesota Historical Society. The St. Louis County Attorney, Warren E. Greene, prosecuted Max Mason and William Miller, and he persuaded the jury to find Mason guilty of rape. Mason, 21, a native of Decatur, Alabama, was sentenced from seven to 30 years. He appealed his case to the Minnesota Supreme Court, but the guilty verdict was sustained. In 1925, the Minnesota Parole Board discharged Mason from prison and banished him.

A total of thirteen African Americans were arrested in relation to the alleged rape, seven men were indicted, and two were tried, according to the Minnesota Historical Society. The St. Louis County Attorney, Warren E. Greene, prosecuted Max Mason and William Miller, and he persuaded the jury to find Mason guilty of rape. Mason, 21, a native of Decatur, Alabama, was sentenced from seven to 30 years. He appealed his case to the Minnesota Supreme Court, but the guilty verdict was sustained. In 1925, the Minnesota Parole Board discharged Mason from prison and banished him.

Attorney Charles Scrutchin convinced the jury to acquit Miller.

Adjutant General W.F. Rhinoq of the Minnesota National Guard was ordered by Governor Joseph A.A. Burnquist to conduct an investigation of the Duluth Police Department. His investigation concluded that the police and Commissioner of Public Safety, William F. Murnian, displayed a “woeful lack of courage, decision, and competency.”

Despite the allegations of cowardice, Murnian was re-elected to the same position in 1921.

Some locals were involved in defending the three African Americans who were lynched, and seeing the murderers prosecuted. Reverend William M. Majors of St. Mark’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, Dr. Milton W. Judy, a dentist, were both active in trying to bring mob members to justice. Judy helped ban sales of postcards printed with a photo of the three lynched men. Even Tusken’s father, William Tusken, said to media at the time that he considered going down to the mob to request they reconsider.

Some locals were involved in defending the three African Americans who were lynched, and seeing the murderers prosecuted. Reverend William M. Majors of St. Mark’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, Dr. Milton W. Judy, a dentist, were both active in trying to bring mob members to justice. Judy helped ban sales of postcards printed with a photo of the three lynched men. Even Tusken’s father, William Tusken, said to media at the time that he considered going down to the mob to request they reconsider.

Two days after the lynching, Judge William Cant and a grand jury issued 37 indictments for the lynch mob, 25 for rioting, and 12 for murder in the first degree. In the end, however, only three people from Duluth were convicted on riot charges.

Carl John Alfred Hammerberg, 18 at the time and born in Sweden, was one of the men convicted of instigating a riot. He served approximately 17 months of a five-year sentence at the Minnesota State Reformatory in St. Cloud.

Louis Dondino, 38 years old at the time, drove his truck around town gathering support for the mob and was also convicted of riot. He served a year at the Minnesota State Prison in Stillwater, paroled in March 1922.

Gilbert Henry Stephenson, 34 at the time, was a carpentry assistant, who testified he helped the mob take lynching victims from their cells. He also served approximately one year at the Minnesota State Prison in Stillwater.

Eighty-three years after the event, on October 10, 2003, a memorial with seven-foot-tall bronze statues to the African American men who were killed was erected across the street from where the lynching occurred. The Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial is the largest lynching monument in the United States.

Tusken, later known as Irene Rosemond Tusken Anderson after her marriage to Elmer Anderson, died in 1996 at the age of 94. Family members described her as being a loving grandmother, and that they were unaware of her involvement in the 1920 lynching, according to media reports.

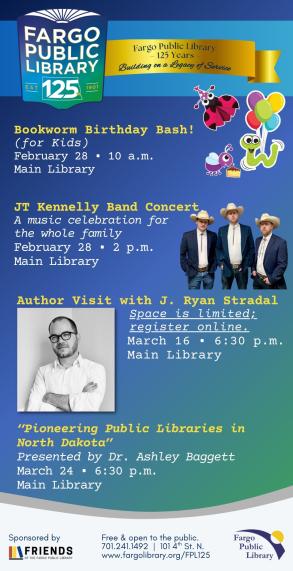

On Thursday, January 25, starting at 6:30pm NDSU Public History researcher Kirbie Sondreal will discuss the legacy of the lynching and the memorial erected in Duluth at the Comstock House. The Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County and the Minnesota Historical Society are hosting the presentation, which has an admission fee of $5, and includes refreshments from Rustica Eatery and Tavern. Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County and the Minnesota Historical Society members admissions are free.

IF YOU GO:

Student Histories: Duluth Lynching MemorialComstock House,

506 8th St S, Moorhead

On Thursday, January 25, 6:30pm

Davin Wait at (218) 299-5511 #6733 or davin.wait@hcsmuseum.org

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)