News | August 1st, 2018

In late June, as thousands clamored to see President Donald J. Trump at Fargo’s Scheels Arena, more than politics were at play. Less than 20 feet from the President’s podium sat current Congressman Kevin Cramer, all smiles, offering awkward man hugs. Doug Burgum, voted Forbes best entrepreneurial governor in the nation and yet cited twice for financial misuse in office, sat next to him. Heir to oil, centralist Kelly Armstrong, brought with him his family’s uncorrupted loathing for anyone anti-Big Oil.

Far away in the upper benches, twice-squeezed by the GOP, yet seemingly content with his lot in life, Tom Campbell, North Dakota spud farmer made good, took a distant, stick-figure-like picture of Trump on stage.

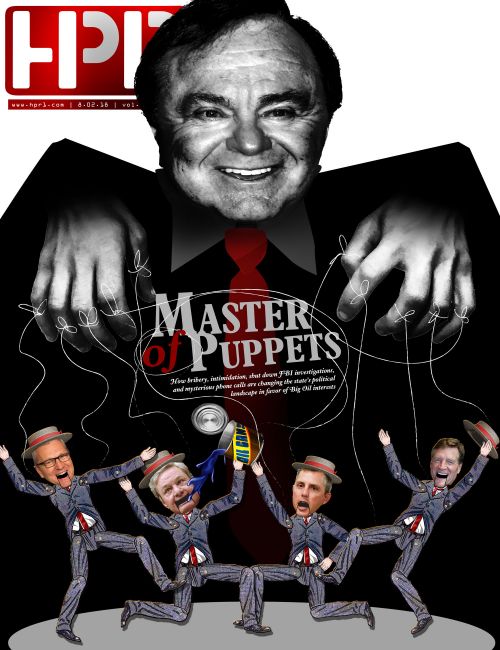

Behind them all, thinning hair combed neatly back, dressed in a crisp dark suit, sat a man Trump mentioned half a dozen times during Fargo’s “Make America Great Again Rally.” The man who turned Bakken straw into gold. The man who invested in North Dakota oil when everyone said it shouldn’t be done. The man who has Trump’s ears, both of them. The man who has pumped millions into the state, collecting politicians and buying university plaques: Harold Hamm, CEO of Continental Resources Inc., the largest leaseholder of oil-drilling rights in the state, and a verifiable master of puppets.

With Hamm at the helm, North Dakota is no longer a flyover state. Hamm’s influence has brought the current U.S. President to North Dakota twice in less than a year, which is no trivial number as only 14 other Presidents have visited since the state’s inception 129 years ago.

Hamm has bought, or invested in, nearly half of the politicians in the North Dakota House. Universities and museums now bear his mark after donating millions. Some say, he’s now influencing politicians with a telephone call or two, and twisting the state’s arm for better oil deals.

In a midterm election year as vital to partisan politics as the race between Cramer and Senator Heidi Heitkamp, a Democrat, also supported by Hamm, rarely has the desperation for dominance in Congress or in the Senate been more tangible. The nation’s eyes are riveted, for if Heitkamp wins, the Republicans lose their majority; if Cramer wins, Democrats could be routed for the foreseeable future.

In desperation, candidates deemed unfit for crucial races were cast aside in attempts to secure the Republican majority. Although Campbell – using a Chinese idiom was “first to eat a crab” – announced his bid for Heitkamp’s Senate seat in August 2017, he succumbed to Cramer after the Congressman finally made up his mind in April. Shortly after the GOP Convention, Campbell threw in the towel a second time for the state’s only seat in Congress, opening the way for Hamm-backed Kelly Armstrong, Republican endorsed.

North Dakotans are beginning to wake up, though, and complaints are trickling in to those who will listen. There is no central office to file grievances when elected or appointed officials are involved in alleged crime; the state has yet to create an ethics commission. Some believe many across the state have had enough of Big Oil strong-arm tactics and once-hungry politicians desperate for a handout.

A mysterious telephone call

Excluding bustling tankers, a controversial pipeline, protests, man camps, cartels, indiscriminately-dug waste pits and radioactive filter socks, drugs, human trafficking, and missing Native women, corruption in the oil fields remained quiet until recently.

Reports from two different sources say that a conversation occurred between Harold Hamm and state Senator Tom Campbell, which made the difference in his recent decision to drop from the Congressional race.

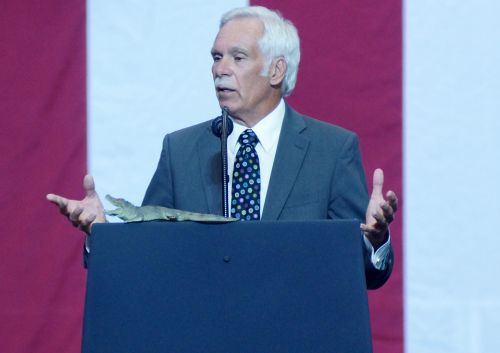

“Well, put it this way,” Campbell said. “I’m a guy of the people, I love people. I put on 45,000 miles in nine months, so I feel I got a little bit shortchanged in the way circumstances turned out, but I will be back.”

Did Hamm make him an offer he couldn’t refuse?

“I was communicated with by some other people that kind of persuaded me not to run, I’ll just leave it at that,” Campbell said. “There’s a whole other side of the story that maybe someday I’ll discuss, for now I’ll probably just remain mum about it. But definitely there are reasons I did what I did, not saying it was right or wrong, it’s just what I chose.”

“I was communicated with by some other people that kind of persuaded me not to run, I’ll just leave it at that,” Campbell said. “There’s a whole other side of the story that maybe someday I’ll discuss, for now I’ll probably just remain mum about it. But definitely there are reasons I did what I did, not saying it was right or wrong, it’s just what I chose.”

Campbell wouldn’t admit if Hamm was the deciding factor for him dropping out, even if Hamm and his net worth of $19.5 billion became the decision maker for Cramer accepting Hamm as his national finance chairman.

“I know Harold, I’m always kind of discussing everything with him, so he was definitely… umm… and I’m always talking to him, and I’m still talking to him of some possible opportunities as well,” Campbell said. “There’s nothing for sure, there’s just some opportunities that I possibly would be open to.”

One report alleged that it was suggested Campbell could possibly be in line for a future ambassadorship. The United States currently has 39 vacant ambassadorial spots around the world.

When asked if he received an offer about an ambassadorship, he said, “If anything like that would come up, I would be open to listening to those options, but no, nothing like that has come up. Who knows? I really don’t know what could happen, but I know people are possibly looking for things for me, so we’ll see what happens, maybe nothing, but... at the end of the day I was overwhelmingly received by the common person.”

In the meantime, Campbell is back to what he knows best, growing potatoes. Campbell is a “spud man,” learned how to operate a potato harvester with his brother Bill in 1978 after buying $11,000 worth of equipment from a neighbor’s farm. He started with 120 acres of red potatoes in the Red River Valley and turned his farm into a part of the national potato industry with Tri-Campbell Enterprises.

Campbell, who raised $1.19 million for his U.S. Senate race, $745,000 of which came from his own pocket, withdrew from the ballot for the June primary yet still received more than 20,000 votes, he said. He is also currently helping his former competitor run for the U.S. Senate, he said.

“I’d like to get back to serving the people,” Campbell said. “Right now, I’ll just sit on the sidelines and I’m ready for the opportunity when it comes.”

On April 11, the same day Campbell decided to withdraw from the race for the U.S. Congress, Governor Doug Burgum congratulated him, saying, “We are deeply grateful to Tom for his selfless decision, which allows the party to focus its time, attention and resources squarely on the critically important races in November.”

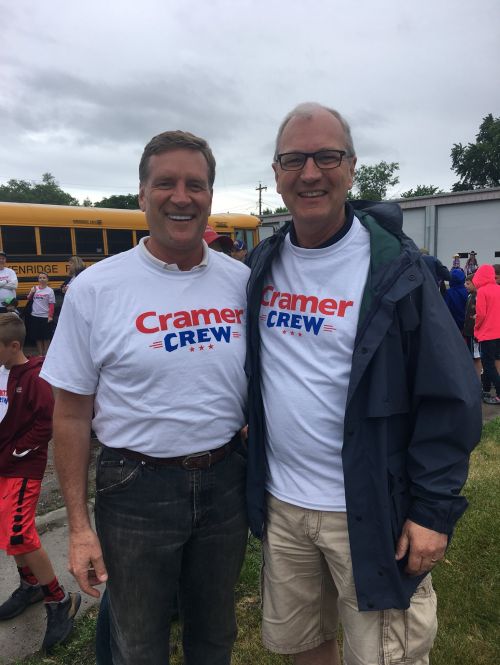

With an unwanted competitor out of the race for U.S. Congress, Cramer also expressed his appreciation.

“There are very few acts I have seen in politics recently that are as selfless as Tom Campbell’s decision to suspend his campaign for the U.S. House of Representatives in the upcoming primary,” Cramer said. “Clearly this was a sacrifice on his part.”

‘For Sale’

The state first planted its “For Sale” sign in the oil-rich Bakken as early as 2011, and big oil began preparing, already for fracking, but more importantly against legislation and tax rates they didn’t like.

Corruption was unveiled in a little-known report filed by Grand Forks attorney David Thompson in 2012, who this year is running against incumbent Wayne Stenehjem for North Dakota Attorney General. Thompson’s report, co-written with attorney Erik A. Escarraman, alleged then Governor Jack Dalrymple accepted bribes from Hamm in exchange for political favors.

“He [Dalrymple] committed Class C bribery at the time,” Thompson said.

The alleged bribery began on January 1, 2011 with a $5,000 gift by Continental Resources Mike Cantrell to former Governor Jack Dalrymple’s campaign, then another gift by Mike Armstrong, a local oil baron and president of the Dickinson-based Armstrong Corporation, on July 21, 2011. Other campaign gifts during 2011 and the first half of 2012 came from ConocoPhillips, Exxon Mobil, Marathon Oil, Hamm’s lawyer Lawrence Bender, and John Hess, among others, totaling $81,600.

The alleged bribery began on January 1, 2011 with a $5,000 gift by Continental Resources Mike Cantrell to former Governor Jack Dalrymple’s campaign, then another gift by Mike Armstrong, a local oil baron and president of the Dickinson-based Armstrong Corporation, on July 21, 2011. Other campaign gifts during 2011 and the first half of 2012 came from ConocoPhillips, Exxon Mobil, Marathon Oil, Hamm’s lawyer Lawrence Bender, and John Hess, among others, totaling $81,600.

Hamm’s gift of $20,000 on December 12, 2011, was the largest. Nicely wrapped in time for Christmas, the donation heralded possible reciprocation – first continuances while oil lobbyists worked their dark magic, according to Thompson’s report. The donations were spaced out in timing to petitions and hearings for continuances on a massive unitization of a Bakken area known as “Corral Creek-Bakken Unit.”

“A mere eight days after Harold Hamm gave his $20,000 contribution to Governor Dalrymple’s election campaign, Dalrymple sat down as the chairman of the three-member Industrial Commission and approved a massive oil and natural gas exploration and production ‘mega unit’ possibly unprecedented in terms of its size in North Dakota history, covering a portion of the Bakken Oil Patch in which Hamm’s company, Continental Resources, Inc. held oil and gas exploration and development leases,” Thompson wrote in his report entitled “Political Campaign Money from ‘Big Oil,’ Governor Jack Dalrymple, and North Dakota’s Class C Felony Bribery Statute.”

Governors and politicians in every U.S. state routinely accept contributions from oil producers, or leaders of industry, but Dalrymple’s case was unique as he was also the chairman of the Industrial Commission, an “omnipotent” power regulating the industry.

“He [Hamm] is as dirty as they get,” Thompson said. He’s never forgotten the bribery case that almost was, and if elected as North Dakota Attorney General this November, vows to clean the state of oil’s corrupting influence. Like most people, he agrees that oil is a vital part of the state’s economy, but the industry needs real regulation from parties not bought and paid for by people like Hamm, he said.

“The dollars don’t seem that big, but the truth of the matter is they are for North Dakota contributions, you got cause and effect here, and you have Harold Hamm’s personal lawyer showing up with 5,000 bucks. He’s the worst of the worst as far as corrupting our politics. Just as we allege Dalrymple broke the bribery statute, he [Hamm] was the giver; Dalrymple was the receiver.”

_former_gov._jack_dalrymple,_sen._john_hoeven,_sen._heidi_heitkamp,_rep._kevin_cramer_and_maj._gen._alan_dohrmann,_north_dakota_adjutant_general_-_u.s._national_guard_photo_by_bill_prokopyk__250-wide.jpg)

Prima facie

Knowing that proving quid pro quo in a bribery case is an almost impossible task, Thompson initially felt confident in his case because state bribery laws are based on prima facie, meaning any superficial evidence is enough to prove a suspect guilty.

All criminal offenses need to be proven without a shadow of doubt, Thompson said, but under a Watergate-era bribery statute, superficial evidence proves conviction if the assumption is not adequately rebutted.

“It clearly states that the case is established by circumstantial evidence, all you have to do is offer or accept a thing of pecuniary value from somebody involved in an interest or in an imminent proceeding, and that action could affect performance or non-performance,” Thompson said.

He, along with others including Minot resident running for the U.S. House this year, Charles Tuttle, and Paul Sorum, a business owner who has run twice for governor, rallied enough signatures for a grand jury, but the state smashed the attempt by pulling the rug out from under their feet.

Thompson couldn’t file the complaint with the North Dakota Attorney General as Stenehjem was complicit, Thompson said. As the legal advisor of the Industrial Commission, the presiding three-person panel that determines the oil industry’s fate in the state, Stenehjem presided over all proceedings.

With few avenues left, Thompson turned to grand jury proceedings, which required the signatures of 10 percent of the residents who voted in the general election of Dunn County, or a minimum of 167 signatures.

Time was running out, however, Big Oil’s fingers were digging deep. Officials may have broken laws nobody would investigate, and then 12 well owners in the ‘mega unit’ lost all but a fraction of their royalty payments. Thompson then discovered Governor Dalrymple owned stock in Exxon Mobil, a company involved in the same ‘mega unit.’ The North Dakota Attorney General was speaking to the Dunn County judge, who was appointed in part by Dalrymple.

The petition came back with 173 signatures, which surpassed 10 percent of the voters who participated in the last general election, as per law then. The complaint was then filed with a Dunn County District Judge William Herauf , who turned to the North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem for help.

“We were focused on Dalrymple at the time,” Thompson said. “But it was a conflict of interest, he [Stenehjem] basically interfered.”

Herauf threw out the petition to investigate Dalrymple on felony bribery charges because too many signatures had postal boxes listed as addresses. He also ruled that Dunn County was not the appropriate jurisdiction to bring the charges, as the Governor’s office was in Burleigh County.

In rural areas, many residents only have post office box addresses.

“That was a cheap shot,” Thompson said. He didn’t carry the petition, Tuttle did, Thompson said.

“We felt that was very wrong,” Sorum said. “The judge didn’t have authority to throw that out or throw people arbitrarily off the petition. We had enough, but if the judge didn’t think that some people lived in that county then he had to prove that they didn’t live there for 30 days. This was in the time of the oil boom, and all you had to do was live there in a trailer for 30 days.

“My eyes were really opened to what was going in the state,” Sorum said. Repeated scandals including Thompson’s lost case led Sorum to believe change was needed.

“Wayne Stenehjem is North Dakota’s Hillary Clinton,” Sorum said. “It’s just one scandal after another.”

Citizen power stripped

After losing an appeal to the North Dakota Supreme Court, the state eviscerated citizen power in grand jury proceedings – regulations nearly as old as the state itself – by increasing the amount of signatures needed from 10 percent of residents who voted in the general election to 25 percent under House Bill 1451.

“Concerned citizens will have no recourse,” Thompson wrote in a petition not to pass House Bill 1451. “I ask you to kill HB1451.”

The legislation spearheaded by Republican representatives Jim Kasper and Al Carlson, passed, with Kelly Armstrong’s signature, in 2013.

Instead of facing the allegations and working with a grand jury, lawmakers – in part supported by Hamm – made sequestering a grand jury too difficult, according to those involved in obtaining petitions. The legislation was a simple tactic to stifle felony bribery charges against Dalrymple, and an effort to protect the status quo, both Thompson and Sorum said.

Even former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who served for 30 years, affirmed a citizen grand jury is separate from the courts and is vital to a nation’s freedom.

“In fact, the whole theory of its function is that it belongs to no branch of the institutional Government, serving as a kind of buffer or referee between the Government and the people,” Scalia said.

“Nobody ever came to us and said your knowledge of the facts are wrong,” Thompson said. “Now they’ve made it much harder to get a citizens’ grand jury.”

“We don’t have law and order right now,” Sorum said. “Now they’ve infringed on our right to have a grand jury. The aristocracy we’ve had running this state is not working. The Industrial Commission has omnipotent power to regulate the industry, but the Industrial Commission doesn’t enforce the law with these producers.”

The Industrial Commission’s charter states that it has the power to investigate all claims or complaints, and hold investigatory hearings in any matter under its jurisdiction. The Industrial Commission also holds the power to bar any person it deems exhibits improper conduct.

The Commission also has a convoluted five-page guideline amended on October 1, 2017, on how to protect its information from disclosure, but it has done little to enforce regulations on the oil industry, Sorum said.

“The Industrial Commission is not enforcing anything,” Sorum said. “Why are you impoverishing the citizens of this state in favor of a handful of producers who have violated their contracts with the state?”

Footnote 9

When concerned citizens broached their concerns over losing mineral rights in 2011 during the unitization process of the ‘mega unit,’ the government replied by saying the issue was already settled: Big Oil would get what they wanted which ultimately led to the largest unitization of the Bakken oil field and a 95 percent decrease in private mineral owner royalties.

Unitization is usually reserved for small areas where oil companies are scraping the bottom of a patch. Law stipulates that public interest must reach 60 percent in order to unitize a dying oil field.

Footnote 9 of Thompson’s report points to the government pushing oil interests through, despite repeated protests and questions by concerned citizens.

“Before we get all up in arms about it, we have a few questions of what the proposal is and if it is going to benefit us or not,” Drew A. Combs wrote on October 20, 2011 to Bruce E. Hicks, assistant director of the Industrial Commission’s Oil & Gas Division. Combs was the director of Minerals Management Division of the North Dakota Department of Trust Lands at the time.

“One of the things that has got us so upset is that they are playing this off as a ‘done deal,’ when we are discussing pad locations and the like,” Combs wrote. “We are just trying to figure out if we should support or protest at the next hearing and if we do decide to protest, we want our concerns to be valid, other than saying, ‘we don’t like it.’”

Several hours later Hicks replied in an email saying, “The record of this case is now closed… another hearing is not being held and the Commission plans to bring an order to the IC [Industrial Commission] meeting on Nov. 21 to dispose of this case.”

The unitization voided all existing royalty contract in the ‘mega unit.’ All contacts became moot.

“You could just see the fear, the intimidation by one governmental agency to another, you can see it in Footnote 9,” Thompson said. “It’s an amazing situation. He can’t disown his email. It’s ugly and it’s gangster like.”

Katie Haarsager, the public information specialist for the North Dakota Industrial Commision Department of Mineral Resources Oil & Gas Division, said any reduction of royalties was temporary.

“If a significant reduction in an individual mineral owners royalty payments occurred it would have been short lived since the unit production double within one year, increased tenfold within two years of unitization and is currently almost 30 times the production rate than at the time of unitization,” Haarsager said.

‘Fix the Tax’ scam

Around the same time, a movement funded by Hamm and led by former Governor Ed Schafer was launched to decrease the amount of oil extraction taxes from 6.5 percent to 5. Schafer traversed the state in a painted bus under the guise of “Fix the Tax,” first declaring his work as a nonprofit group was focused on lowering oil extraction tax rates, but later admitted that the group was funded solely by Hamm. Schafer was later given nearly a million dollars worth of shares in Hamm’s company, Continental Resources Inc. on November 2, 2011, and took a seat on Continental’s board of directors. Schafer lost his seat on the board in 2015.

“Here’s the guy who was involved in Ed Shafer’s “Fix the Tax” deal, that was presented as a grassroots thing, here he was in small town North Dakota asking for contributions,” Thompson said.

Despite the scam, on January 22, 2016, the oil extraction tax rate was lowered from 32-year-old original level of 6.5 percent to 5 percent of the gross value at the well of oil produced, according to the North Dakota Office of State Tax Commissioner, Ryan Rauschenberger.

Lynn Helms, an alternate member of the Department of Interior’s Royalty Policy Committee, is also the director of the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources. His mission is twofold: to promote the oil industry and to regulate. His office was contacted for comment, but none was received. Questions were directed to Katie Haarsager, the public information officer.

Stripper wells

A third Big Oil attack came with the addition of stripper wells, defined as oil wells that are scraping the bottom of a patch. State policy stipulates that a lowered tax rate of 2 percent are to be levied against such wells outside of the Bakken, and no taxes against qualifying stripper wells inside the Bakken, but where one stripper well exists, many others follow in order to escape taxes.

“The presence of one stripper well could immunize the entire 30,883.94-acre ‘mega unit’ from contributing to oil extraction tax revenue to the State of North Dakota,” Thompson wrote in his report. “Governor Jack Dalrymple, immediately caused a potential loss of dozens of millions of dollars in oil extraction tax revenue for the State of North Dakota, as well as the nullification of contingent lease term provisions in the many oil and gas lease contracts between mineral interest owners – both private individuals and state-owned whose property lies within the contours of this ‘mega unit.’

“Furthermore, evidence exists that the establishment of this ‘Corral Creek-Bakken Unit,’ which was directly created by Governor Dalrymple’s official adjudicative action as chair of the three-member of the North Industrial Commission – has severely reduced royalty payments for private mineral interest owners of tracts…”

Despite the addition of stripper wells in 2011, oil in the ‘mega unit,’ today is abundant.

Katie Haarsager said today, the Corral Creek-Bakken Unit has 151 wells that produce around 130 barrels of oil a day. One well qualified for stripper status in 2013.

In 2018, Hamm reassured investors that North Dakota’s oil is far from empty. In 2011, approximately 12 wells existed in a portion of the ‘mega unit’ that today has more than 280.

“We’re a long ways from the bottom of the barrel that we saw early last year so the prices today are what we consider good,” Hamm said on CNBC. “The Bakken is back stronger than ever, the technologies work better there than anywhere else. We’re still in the third inning of the Bakken development.”

FBI

Two years after the state shut down grand jury procedures, Thompson found himself sitting in a federal office room with agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The agency, he said,was looking into corruption allegations against the Oil & Gas Division of the Industrial Commission.

“I know there was an FBI investigation because I sat down in a room with FBI agents,” Thompson said. “It was shut down after Trump came into office in 2017.”

By the summer of 2014, the FBI reported they had no federal case, but the investigation remained open.

Corruption in the state even caught the humorous banter of HBO’s John Oliver in 2015, who purchased a sign along a Minot highway saying “Be Angry. (Please).”

For 20 minutes Oliver spoke about the over-friendly, “pretend everything is okay” attitude the state exhibits toward oil companies, describing the state as a “magical utopia like Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, which, come to think of it, had about the same safety record as North Dakota’s oil fields.”

The majority party’s money trail

“The corrupting influence is a massive infusion of oil and gas money into our political system, and that is the central corrupting influence.”

– David Thompson

“Before fracking North Dakota was always this state starving for more money, more tax revenue, and with the fracking it tempts people in office to have their hand out.To be taken to lunch. To go to New York for nice dinners, whatever, who knows what else.”

– Paul Sorum

After decades of trial and error in the oil fields, pockets of grassroots resistance are developing, and corruption reports are stacking up, a person who wished to remain unnamed but has been affected by the oil boom said.

“We need to change how things are structured in Bismarck, in our capitol,” Sorum said. “We need to structure things in our state government to handle the newfound revenue, to handle the regulation, to handle the court cases, we just need to restructure a little bit, and we will be fine. We need to do it sooner than later, to make these things work again for the benefit of people who live here in the state.”

The money trail can be followed to approximately half of the elected officials in the North Dakota House. Since 2010, Hamm’s company, Continental Resources, has donated $833,475 to politicians, 44 of whom are from North Dakota, and all but six are Republicans.

The money trail can be followed to approximately half of the elected officials in the North Dakota House. Since 2010, Hamm’s company, Continental Resources, has donated $833,475 to politicians, 44 of whom are from North Dakota, and all but six are Republicans.

During the past seven years, Hamm has personally invested a total of $1,606,355 in politicians, 41 of whom are from North Dakota, according to Follow the Money. Most of his choices are Republican; he’s personally given to only four Democrats, including Heitkamp, a United States Senator. His direct picks under his name include the state’s highest office with a small personal donation to Governor Doug Burgum, to Senators, and legislators.

The North Dakota House has 94 elected members, 81 of whom are Republicans; the state Senate has 47 elected members, 38 of whom are Republicans.

From 1976 until 2010, the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Illinois Integrity Initiative has compiled federal data to evaluate levels of corruption in every state and the District of Columbia. North Dakota, with the third lowest population rate of approximately 755,393 in America, ranks the sixth most corrupt state in the nation, with a total of 118 corruption convictions among public officials.

Hamm, 72, is the 13th child of Oklahoma sharecroppers, and was listed as the 164th richest person in America in 2009, with a net worth of $42 billion. Today, the CEO of Continental Resources no longer made Forbes richest-of-the-rich list after losing billions during the recent oil bust. He has a net worth is $19.5 billion, according to Forbes. He throws money around to get his way, paying his ex wife $975 million in cash when they divorced in 2014.

As national eyes are on North Dakota during this year’s election, so are funds pouring in to sway the vote with out-of-state dollars. So far, Cramer has raised $3.2 million, with more than 62 percent coming from out of state. In comparison, Heitkamp has raised $5.4 million, of which approximately 92 percent has come from out of state.

Hamm, with his billions in North Dakota oil profits, became Cramer’s national finance chairman in February, which was a deciding factor in Cramer’s flip-flopping stance on whether to run against Heitkamp, or not.

Hamm’s company, Continental Resources, is based in Oklahoma, and has also contributed $1,204,950 in campaign funds in 2018, according to Open Secrets, Center for Responsive Politics.

For years, Hamm’s money trails to Cramer branches like tributaries of the Missouri River. Sometimes donations are direct deposits to Cramer, at other times the funds are processed through PACs and committees. More than 50 percent of Cramer’s funds for his U.S. Senate run have come from large and primarily out-of-state contributors such as Energy Transfer Partners, the parent company of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

In 2018, Continental Resources has given $7,400 directly to Cramer, and Hamm has personally signed over $8,100 to Cramer in two different installments.

The oil magnate also donated $50,000 to the Cramer Victory Fund, a joint fundraising committee, which then shoveled $155,282 to Cramer this year. Another $5,000 of Hamm’s money went to the Badlands PAC, also a committee for Cramer, which so far has sent $72,440 on to Cramer.

Hamm gave $33,900 to the National Republican Senatorial Committee, a Republican campaign group for the Senate, which donated $80,376 directly to the Cramer Victory Fund.

The joint fundraising committee supplied a total of $155,000 to Cramer’s campaign, more than $72,000 to the Badlands PAC, and $65,000 to the National Republican Senatorial Committee, according to the Open Secrets, Center for Responsive Politics.

The National Republican Senatorial Committee has raised a total of $75,012,050 in 2018, and already spent all but approximately $18 million. Koch Industries takes the number one spot with total donations to the National Republican Senatorial Committee of $955,800.

Kevin Cramer is tied for the top recipient after receiving $47,000 from the National Republican Senatorial Committee.

Top recipients of the Badland PAC include Kelly Armstrong, one-upping President Trump, with a donation of $14,100. Cramer has received a total $7,400 from the Badland PAC, according to Open Secrets, Center for Responsive Politics.

In 2012, Hamm, dubbed by Trump as the “king of energy,” was recognized as one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world, and is an unofficial energy advisor for President Donald J. Trump.

Public filings in the same year, however, showed that Hamm’s political donations exceeded legal limits of $117,000 for individual donations to political parties and political action committees or PACs during the 2011 to 2012 election period.

Many of Hamm’s contributions during the 2012 election period totaling $367,050 targeted “North Dakota’s finest,” including at least $10,000 to Cramer. Hamm, and his hunting buddy Michael J. Armstrong were both on Cramer’s finance team and were charged to help raise monies for Cramer’s 2012 U.S. House of Representatives race.

Cramer won that race. With Hamm’s help and donations from the coal industry, which he regulated at the time as a Public Service Commissioner, Cramer beat Democrat candidate Pam Gulleson.

Michael Armstrong, a North Dakota oil tycoon is also worth billions, is Kelly Armstrong’s father. In addition to being president of the Dickinson-based Armstrong Corp., an oil company, Michael, or Mike Armstrong is a co-owner of Heart River Ranch, and was sued for negligence in 2004 after a prairie fire.

Not surprisingly, Armstrong beat the plaintiffs, with help from Mitchell Armstrong, a Bismarck attorney for Smith Porsborg Schweigert Armstrong Moldenhauer & Smith, according to court documents.

Mike Armstrong is also listed on the executive board for the North Dakota Petroleum Council.

Six years ago, oil money began pouring into the state, and was focused primarily around the 36th Legislative District and Kelly Armstrong. He raised a total of $20,750 in 2012 to run for a seat on the state Senate, with $17,500 coming from oil company PACs or drilling companies. Of that amount, $4,000 came from Michael Armstrong, and $10,000 came from Thomas and John Jordan, a California father and son combination who partnered with the Armstrong Corporation.

In 2016, Armstrong raised another substantial amount of $12,825.66, according to the North Dakota Campaign Finance Office, with a large chunk coming directly from Continental Resources, Coal PACs, and oil PACs.

More than $375,000 from oil interests went to former Governor Jack Dalrymple, who fought tooth and nail to stymie the protests during the Dakota Access Pipeline controversy. Kelly Armstrong was also an advocate for oil company rights during the same time, and prominently featured in his first U.S. Senate campaign for the U.S. House his hatred toward anyone that would disrupt Big Oil’s profit margins.

“I worked hard to increase the penalties for rioting, and to make sure that illegal protesters can’t hide behind masks to conceal their identity,” Armstrong said in his campaign advertisement.

Wayne Stenehjem is also supported by Big Oil, with a total of $84,351 in donations from the oil and gas lobby, according to Follow the Money. The North Dakota Petroleum Council donated $13,951. Hamm directly gave $6,500 and Continental Resources donated another $2,000. Other donations came from Mike Armstrong, Marathon Petroleum Corporation, Exxon Mobil, the ND Oil Pac, Valero Energy, ConocoPhillips, and the American Gas Association, among many others.

Former Governor Dalrymple ran in five races for public office raising a total of $9,518,598, according to Follow the Money, with a total of $554,652 coming from the oil and gas lobby. Drew Wrigley, Dalrymple’s lieutenant governor, who ran successfully in one race, raised $3,593,179, solicited $378,155 from the oil and gas sector. Most of what both Dalrymple and Wrigley raised is listed as “uncoded” donations.

Information obtained from Continental Resources stated that the company donates heavily to research and education, including the State Historical Society of North Dakota for the North Dakota Heritage Center’s Inspiration Gallery, University of North Dakota Hamm School of Geology and Geologic Engineering.

Senior Vice President of Public Relations for Continental Resources Kristin Thomas said the premise of corruption is “a little daunting.”

“I can say broad brush, Harold Hamm is one of those who has integrity like rarely someone I’ve ever known in business,” Thomas said. “We’ve been in North Dakota for 25 years, so we are not people who just jump in and out. We’re committed and it’s as much home as Oklahoma.”

“We take words like corruption very seriously, if there is something that we need to know about and ferret it out, in terms of payments or anything like that, our ethics and compliance program will get involved, and we will be on it, ” Brooks Richardson, the assistant general counsel for Continental Resources, said.

Dalrymple could not be contacted for comment. Calls and emails were directed to Wayne Stenehjem and Kelly Armstrong, but they also did not reply.

‘It’s just how it is’

If you’re not for Big Oil, you’re against it; there’s no grey area in much of North Dakota. Citizens who speak out against state management in the oil regions are ostracized, ignored, and sometimes threatened. Protesters, both in state and out, are shot with bean bags, hosed with water cannons, sprayed with pepper spray, then arrested, by the hundreds. Politicians who speak their minds in favor of the common man, lose favor, and slip quietly into the background.

Paul Sorum, owner and president of Sorum Design-Build, and a founder of North Dakota’s Tea Party, ran an independent campaign against former Governor Dalrymple, and as a Republican in 2016, but lost.

“That’s the number one political weapon to marginalize people in this state,” Sorum said. “They do it to everybody, absolutely, big time for me. There are a lot of people in the state who are intimidated by Big Oil and some of that influence goes all the way to Washington. There’s no question about that. I think there are elected officials, statewide officials, and legislators, even judges, who are intimidated by these people. They have a lot of money, and a lot of power, and that’s just the facts.

“It’s just how it is.”

Today, private citizens have a difficult time addressing their grievances over oil issues in court, Sorum said.

“There’s a lot of deference, they pay deference to the Industrial Commission, they just do,” Sorum said. “It’s their tradition in the state. That’s why the idea of a special master could help the judges defray the time and complexities of these cases. I think that really needs to happen.”

“There’s a lot of deference, they pay deference to the Industrial Commission, they just do,” Sorum said. “It’s their tradition in the state. That’s why the idea of a special master could help the judges defray the time and complexities of these cases. I think that really needs to happen.”

Thompson, wispy white hair and black-rimmed glasses, presents an imposing figure behind any podium. He’s a graduate of the University of North Dakota School of Law, and cut his teeth in the North Dakota Legislative Assembly’s legal staff. In his private practice, he primarily focused on workers and families suffering from diseases caused by asbestos and chemical exposures. He knows how deep the corruption and intimidation tactics go in North Dakota.

“I’m not aware of being threatened directly, but they probably know if anyone did I would proceed against them any way possible,” Thompson said.

Katie Haarsager encouraged anyone who feels threatened or who is knowledgeable of regulatory missteps to come forward.

“We do ask if the public is aware of any operators in violation of state law that they contact the proper authorities,” Haarsager said. “If the violation is under the purview of the Oil & Gas Division we ask that you also reach out to our staff to investigate the violation as well.”

The Industrial Commission meets on a monthly basis, and considers recommendations from the Oil & Gas Division, who are considered experts in their fields, Haarsager said.

“The Oil and Gas Division always conducts public hearings in a very professional manner, never threatening, intimidating, or cowing individuals into silence,” Haarsager said. “The public hearings are live streamed world-wide over the internet so any such behavior would immediately become public knowledge and dealt with appropriately. The Oil and Gas Division, under the control of the Industrial Commission, provides regulatory oversight and in many cases authority over oil and gas development in the state. The Oil and Gas Division staff and leadership fully enforce all rules and regulations that govern oil and gas activity as outlined in the North Dakota Century Code and Administrative Code.”

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)