News | April 13th, 2017

_lissa_yellow_bird-chase_on_hunt_in_badlands_-_photo_by_c.s._hagen__250-wide.jpg)

Missing persons posters are everywhere, stapled to telephone poles, taped to post office doors, fed through Facebook feeds and chats. They pop up every few days as desperate cries from the families of loved ones who suddenly disappear.

The posters are usually ignored until the tragedy hits home, victims say. Sometimes, the missing are found, but most of the time their trails grow cold.

Police either don’t file reports or have no more leads, and that’s when Lissa Yellow Bird-Chase picks up the hunt.

A body hunter’s untiring enemy is spring, with all its melting snow. While the days lengthen and the sun thaws the prairie grasses, Lissa Yellow Bird-Chase enters what she calls panic mode.

Ponds flood, potentially covering evidence. Prairie grasses can grow up to seven feet tall. There are cadaver dogs to arrange, volunteers to enlist. Preparations take money, which comes in the form of donations and from her own pocket book. On the Dakota plains, snakes stir, looking for warmth. Coyotes grow brave from lean winter months and begin to scavenge.

“I got tracked by a mountain lion once, and chased by a few buffalo,” Yellow Bird-Chase said. Most summer weekends she spends searching for corpses on the North Dakota plains. “Almost got the snot slapped out of me by a badger. Adds character, my son told me.”

Formerly a bounty hunter, she’s now a body hunter, an independent “seeker for the missing,” who like the badger, never gives up the hunt. The dead leave clues, sometimes hidden within juniper bushes or a few feet under disturbed topsoil in the Bakken oil patch. Clues point to trails - linked piece by seemingly inconsequential piece, sometimes hundreds of miles long.

Many missing persons’ cases delve deep into North Dakota’s underworld of drugs, human trafficking, and cash-hungry oil workers. Yellow Bird-Chase has worked cases where men have been buried alive, where women have been shot execution style, and cases fit for a television miniseries season of “Fargo,” such as the double homicide-for-hire case stretching from North Dakota to Washington.

“I’ve always been good at scouting people out,” Yellow Bird-Chase said. She is a Fargoan, and the founder of the nonprofit group Sahnish Scouts of North Dakota, a citizen-led organization dedicated since 2014 to finding missing people for their families. Sahnish means “the people” in Arikara.

“If we knew there were dead somewhere, we would go and try and recover them,” Yellow Bird-Chase said. Her group started as a recovery team in the Bakken oil fields, and over time built a reputation.

Her work attracted the attention of the New York Times and Associated Press. Soon, the cries for help began pouring in. She has worked on dozens of missing persons’ cases over the years, and is currently focused on the case of Ron Johnson, who at 74 years of age went missing near Spirit Lake in 2011.

She is also working the cases of: Kristopher “KC” Clarke, 29, Damon Boyd, 29, Edward Ashton Stubbs, 15, and Joseph Lee, 44, and her investigations take her to primarily four states: North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Montana.

Yellow Bird-Chase, 49, is part Arikara, part Mandan, part Hidatsa, and a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. She’s patient as a bullsnake, nimble as a Bighorn Sheep leaping over “quick mud” and gullies. Deer, pheasants, and mountain bluebirds stop to watch. She calls to them.

“Hey you, have you seen K.C.?”

She’s been searching for Kristopher “K.C.” Clarke for nearly five years. The 29-year-old’s murderers are behind bars, but his body has never been found.

Cl arke was killed by a murderer-for-hire on February 22, 2012 after he left the overworked employment of his one-time Texas friend, James Terry Henrikson, “the boss,” an owner of the trucking company Blackstone, LLC. She began combing a part of the Badlands near Theodore Roosevelt National Park nearly two years before police caught the killers and obtained confessions.

arke was killed by a murderer-for-hire on February 22, 2012 after he left the overworked employment of his one-time Texas friend, James Terry Henrikson, “the boss,” an owner of the trucking company Blackstone, LLC. She began combing a part of the Badlands near Theodore Roosevelt National Park nearly two years before police caught the killers and obtained confessions.

She’s not psychic, she said; she simply has indescribable feelings, instincts, at times even forewarnings. Before police solved the case, she said she was threatened and her car wheel fell off on the interstate near Valley City. Not long after, the same thing happened to her daughter’s car, she said, which proved foul play. The murderers were trying to get rid of her, another on their growing hit list, she said.

The searches intensified, and after five years she believes she is close to finding Clarke’s final resting place. She’s waiting on cadaver dogs, and even if the next massive search toward the end of April doesn’t succeed, she’s not giving up.

“I’ll find him,” she said. Stratigraphic columns filled with layers of black coal, red fossil soils, and yellow paleosol fill her hunting ground behind her like a natural canvas, more precise and rugged than any Georgia O’Keeffe painting.

Yellow Bird-Chase’s fingers are blackened from her day job as a welder, she works her “true calling” every summer weekend and most every other winter weekend. During the weekdays she works from her Fargo apartment, papers piled from dining room to office, an organized mess, she says, but still knows where everything is.

During the years of searches, she experiments with the earth, sometimes filling holes with watermelons and then filling them in to see what happens to topography a year later; other times studying a corpse’s bone scatter by wild animals.

Yellow Bird-Chase has three rules for everyone who helps on her searches: don’t fall behind, come prepared, and never lie.

The oil murders

Yellow Bird-Chase’s mission to find the missing and the dead began shortly after her release from prison on drug-related charges.

“About five years ago one of my aunt’s daughters called me and said, ‘Hey, there’s this white kid whose name is K.C. Clarke working in the oil fields and he went missing.’” Yellow Bird-Chase said. “He was white, and went missing on the rez.”

She slipped into the gray area -- the no man’s land between sovereign tribal law and U.S. and state governments, she said. Native American communities fall under a combination of tribal, state, and federal laws. The Federal Bureau of Investigation is primarily responsible for investigating and prosecuting federal crimes such as murder and rape; misdemeanor cases are mostly prosecuted by tribal law enforcement, or the Bureau of Indian Affairs, who are typically first on any crime scene.

The law also differentiates Native American from the non-native, meaning BIA cannot investigate a crime committed by someone not belonging to the reservation, and federal or state police typically have legal troubles investigating a crime committed by a native who is on the reservation. Poor communication between tribal law enforcement, state, and federal authorities, inadequate resources, and an increase in crime lead to a “maze of injustice” and loopholes those who know how to work the system can exacerbate.

As a Native American and private citizen, Yellow Bird-Chase could help investigate both worlds, she said.

“It was a jurisdictional conundrum, a big circle of jurisdictional denial,” she said. “At first, I was like, yeah, okay, whatever, but that started the big K.C. adventure.”

Clarke’s murder led in part to the downfall of Fort Berthold Indian Reservation Chairman Tex Hall’s tight-fisted rule, and also to the arrests and later convictions of five men involved in two murders over Bakken oil money.

According to court documents of the United States District Court Eastern District of Washington, Henrikson hired Tim Suckow, 53, aka “Donald Duck,” to kill his former friend for $20,000.

Clarke was a personable guy, according to Scott Travis Jones of the United States Attorney’s Office, who liked motorcycles. Yellow Bird-Chase agreed, but said the young man also had problems, like everyone else. Clarke became a salesman for Blackstone as he was constantly at customers’ job sites. He worked 24-hour-shifts, showered, and went out on another 24-hour shift repeatedly. He lived out of his pickup truck and was not happy about it, Jones said.

Clarke was a personable guy, according to Scott Travis Jones of the United States Attorney’s Office, who liked motorcycles. Yellow Bird-Chase agreed, but said the young man also had problems, like everyone else. Clarke became a salesman for Blackstone as he was constantly at customers’ job sites. He worked 24-hour-shifts, showered, and went out on another 24-hour shift repeatedly. He lived out of his pickup truck and was not happy about it, Jones said.

Clarke decided to jump the fence for Running Horse Trucking, a competitor of Blackstone, due to the mistreatment.

The decision “enraged” Henrikson, according to Jones, who said “He was going to kick K.C.’s ass, kill K.C., and that K.C. was stealing contracts from him.” His thoughts turned to murder, and he ordered Clarke to go on a mandatory vacation for two weeks.

Hardly halfway through the vacation, Henrikson, through his wife at the time, Sarah Creveling, called Clarke back to “the shop,” a building the company worked out of, which was situated on Hall’s property. After Clarke put a new handgun back into his pickup truck, Henrikson distracted Clarke with a new motorcycle while Suckow snuck up behind him and smashed him in the head with a floor jack, a tire-changing tool used for semi trucks. Four blows, and Clarke’s skull “went soft,” Suckow said.

Clarke’s truck was first dumped outside of Watford City, and later moved to Williston, where the vehicle sat for four months along the side of a road, according to court documents. Clarke was put into a toilet box and buried in the Theodore Roosevelt National Park. His handgun, a .45, was shredded by a Sawzall, and the barrel crushed.

For

Yellow Bird-Chase said she learned about ill intentions toward Carlile and warned him twice. Both times, Carlile was more worried about his investments and didn’t take the threat seriously.

Once again, Henrikson turned to Suckow, who, along with accomplices Robby Wharer and Lazaro Pesina, later confessed to both murders, saying they were following Henrikson’s orders.

Other Blackstone investors and a former business partner were targeted by Henrikson, according to court documents. One man on Henrikson’s hit list, Jed McClure, escaped unscathed after Todd Bates, hired Chicago hitman Martin Marvin “The Wiz” to kill McClure. McClure was also an original investor in Blackstone who claimed early on that Henrikson and his former wife were fraudsters, and were complicit in Clarke’s disappearance.

Jay Wright, a former employee, and Tim Scott, to whom Henrikson owed money, were also on Henrikson’s hit list, according to court documents.

The entire ordeal began with rights to work on Native American lands. Henrikson obtained three Tier 1 “TERO” cards, which helped him obtain special preference for bidding on contracts, according to court documents. After being fired from two companies, Henrikson’s vehicle “conveniently broke down in front of Chairman Tex Hall’s home.” He asked for help, and over time Henrikson and the chairman struck up a business partnership, according to court documents. Although Hall denied they had a relationship outside of business, Henrikson took Hall’s adopted daughter, Peyton Martin, as his mistress, and both men were photographed together while on vacation in Hawaii.

Henrikson is currently serving two life sentences plus thirty years in a high-security penitentiary in Florence, Colorado, according to the Bureau of Prisons. His right-hand hitman, Suckow has found religion and is serving a total of 30 years for both murders. Wharer is serving 10-year sentence for driving the getaway car, and Pesina a 12-year sentence for breaking into Carlile’s home. Others involved are also serving time behind bars.

The hunt goes on

Before Clarke’s murder was solved, Yellow Bird-Chase posted more than 50,000 fliers, she said. She met with Homeland Security, sheriff’s deputies and court officials regularly, trying to learn news of Clarke’s body. Clarke’s family and information off the Internet helped direct her searches, but she still searches.

Not long after her release from prison, Yellow Bird-Chase said her initial involvement in hunting the missing and the dead changed her life.

“I

She missed the first years of North Dakota’s oil boom, and when she returned to the area to search for Clarke’s body, she experienced a type of culture shock, she said.

“Buzzing traffic, oil workers, oil drills pumping up and down. I had to acclimate myself to this whole situation. There were a million people all over the place where before there wasn't anybody.”

Her search for Clarke’s body so far has been comparable to “looking for teal-covered sand at the bottom of the ocean.” Clarke’s body was identified by both men who assisted in his death and ensuing coverup, but both men pinpointed the burial site with a difference of a quarter of a mile, according to court documents.

In those days, law enforcement rarely helped her, she said. “I’m kinda known as the fire under people’s asses,” she said. “I will call them out, I will go to jail for it, I don’t care. If someone has a missing family member, I will find them. I know what to do. If the police have a problem with that, how are you going to deny a family their loved one? It’s either you don’t care or you’re just lazy. Or maybe you’re not educated and you don’t know what you’re supposed to do.”

She has distracted police while her volunteers fan out to search, once finding a body that had evaded police for hours within thirty minutes, she said.

“Before I was met with, ‘You can’t be here, or you’re impeding an investigation,’” she said. “They used to see me as a threat, now they see me as a threat that won’t go away. Now we have the full cooperation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and we’ve even been offered assistance on any reservation in the United States from that department.

the full cooperation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and we’ve even been offered assistance on any reservation in the United States from that department.

“It’s been a long time coming, but it made a complete turnaround.” She’s even had “anonymous tips” from law enforcement leading her in directions the police didn’t go, she said.

Morton County Sheriff’s Department declined to comment on one case Yellow Bird-Chase is working on in their jurisdiction, according to Morton County Public Information Officer Maxine Herr.

Official statistics aren’t accurate, she said. Rarely do families report missing people immediately, and police sometimes fail to file a report, which is crucial for discovering information on national databases on any potential victim. Many of the missing are victims of crime, but many more fall prey to human trafficking.

NamUs, the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, reports North Dakota currently has 31 open cases of missing people.

Reports of human trafficking in North Dakota have been on the rise since 2012, according to the Human Trafficking Hotline Center. In 2016, a total of 66 calls were made, resulting in 19 active cases, compared to a total of six human trafficking cases in 2012.

Director of the state’s human trafficking coalition FUSE (Force to End Human Sexual Exploitation), Christina Sambor, reported that the North Dakota Human Trafficking Task Force assisted with 79 cases of human trafficking in 2016. A total of 66 victims were involved in sex trafficking, while 26 victims were children.

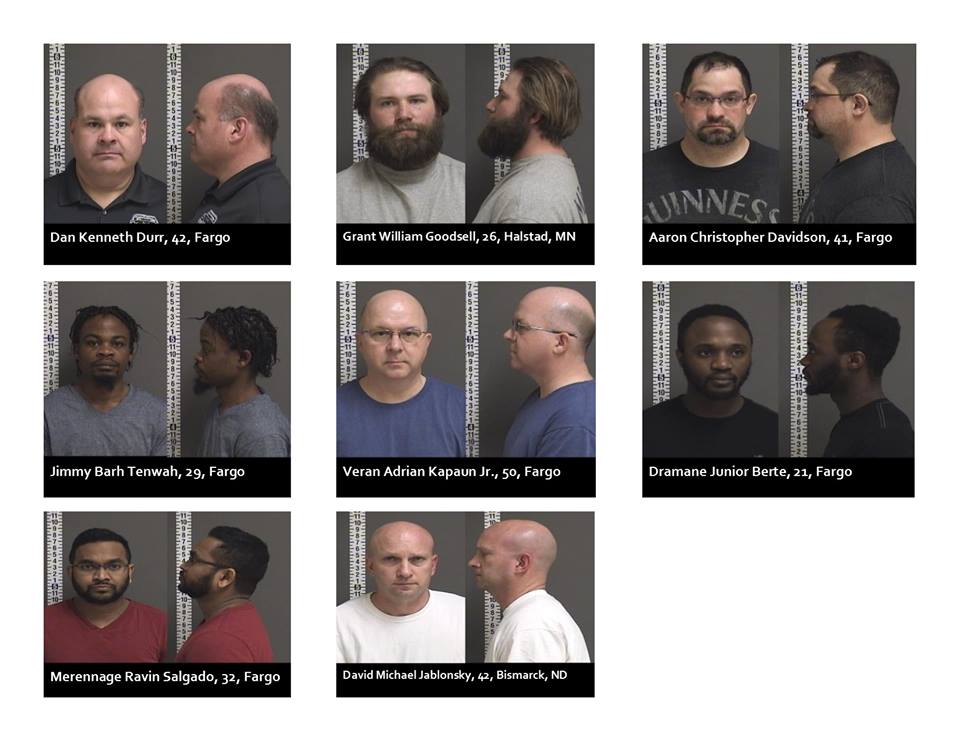

Fargo’s most recent trafficking case ended on March 10, when nine people were arrested in a joint undercover operation, according to the Fargo Police Department. Among those arrested, five were from Fargo, one was from Bismarck, one from Grand Forks, and another from Halstad, Minnesota. All face felony arrests for Patronizing a Minor for Commercial Sexual Activity, a Class A felony punishable by up to 20 years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

One of the men arrested was Dan Kenneth Durr, 42, president and CEO of Don’s Car Washes, Inc. Don’s Car Wash began in 1958, and Durr took over the company as president after Duane Durr retired, he said in an interview on Fargo/Moorhead/West Fargo Chamber of Commerce.

Although Native Americans in North Dakota comprise only five percent of the population, they are the hardest hit ethnic group from human trafficking, according to North Dakota Council on Abused Women’s Services or CAWS North Dakota.

“The rate of violent crime estimated against Native Americans is well above that of other U.S. racial or ethnic groups and more than two times the national average,” CAWS North Dakota reported.

Senator Heidi Heitkamp D-N.D., is an avid fighter against human trafficking, and released a podcast earlier this year called “The Hotdish,” a platform for discussing issues to combat the traffic of abducted humans.

“Human trafficking is a serious problem worldwide, and unfortunately North Dakota is no exception,” Heitkamp announced on her U.S. Senate website. “North Dakota is no stranger to this horrible crime. Places like Minot, where we rescued a 12-year-old and a 14-year-old when their mothers discovered them on Backpages,” Heitkamp stated in her podcast. “How in the world can we allow that to happen in our country?”

She highlighted a website called Backpage, reportedly a major facilitator of human trafficking. A report released to the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs’ Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in early January cited Backpage on its role in trafficking, particularly with minors.

Although Backpage CEO Carl Ferrer refused to comment during the hearing, the website shut down the adult section of its website, according to the U.S. Senate.

Yellow Bird-Chase said statistics don’t reflect reality. “For North Dakota, as big of denial as they’re in, it’s not so much that it has increased, for population, it’s probably the same. We have a new culture of sex workers here, and they’re not afraid or are inhibited by letting people know what they’re up to. It’s always been here.”

Because of Yellow Bird-Chase’s past, she can’t become a private detective, she said. She loves her job as a welder, but her true calling always beckons. She is searching for a grant writer, and volunteers help with raising funds.

“I would like to do this full time, but I’m not going to have an agency telling me what is a priority case.”

Dozens of missing persons are listed on the Sahnish Scouts of North Dakota Facebook page. Most are young and female; some are children.

“When you don’t have any closure it’s hard to know how to grieve,” Yellow Bird-Chase said. “Some people just write it off and don’t talk about it ever again. And there’s some people who talk about it nonstop night and day, and they die of a broken heart because they never find out what happened to their loved one.”

All missing people should be reported immediately, and family or friends should obtain a report number, she said.

“If that person is missing for five seconds, you can call it in and they have to take a report. Get that officer’s name and the report number. Once you get that report number, call me.”

To support Yellow Bird-Chase and the Sahnish Scouts of North Dakota, donations can be made to: https://www.youcaring.com/sahnishscoutsofnorthdako...

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

January 16th 2026

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)