News | April 6th, 2017

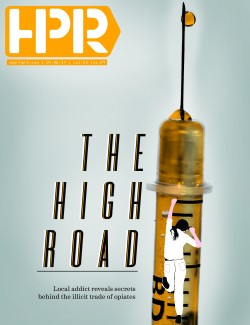

“Jackie” isn’t ready to come out with her real name yet. She’s a heroin addict, a Fargoan clean for nearly a year. In her 20s she overdosed three times, then carried an overdose reversal drug in her wallet, which saved her life. She shot “downs” or heroin, free-based “ups” or methamphetamine.

One of the main questions she used to ask was, “Does it have legs?” Pure heroin, sometimes laced with fentanyl and known in the Upper Midwest as “China White,” has “legs” about as long as a spring day, less than 12 hours. It comes as a white or silver grey powder known as “gunpowder,” as patches imported from China, or as a black tar mostly from Mexico, and it claimed 13 lives in Fargo in 2016.

“It’s instant euphoria, like a warm blanket,” Jackie said. “Nothing else matters, the world just dissolves. At the same time music sounds better, colors look sharper and brighter, gives you a false sense of swagger. I’m usually kind and gentle, but what I regret most is doing things that were against my values: stealing from stores, from friends and family, to sell -- dining and dashing, lying, pawning my guitars, amplifiers, and television for drug money.”

Her plunge into the underworld began as a teenager, started with a little marijuana and a prescription. She never meant to become addicted to opioids, but the prescriptions for Xanax and Klonopin, an anti-epileptic medication also used to treat panic disorders, helped ease her into street drugs.

“Klonopin lowered my inhibitions, made me apathetic and ambivalent,” Jackie said. “It begins to kill a lot of your passions for things. I don’t blame it on that, but it made me care less, and I put myself in risky situations.”

At first she dabbled, shot heroin only on the weekends, but availability became easier from friends who called themselves bums, sitting outside grocery stores waiting to sell or trade. Smart dealers and buyers hide in plain sight, she said, making drug transactions in daylight.

She turned to heroin, snorted it, and eventually began shooting it into her arm. “For most people they say they will never use the needle, but the further you go down the ladder you use it because you need less of the drug to get you by.” Heroin’s effects are purer when shot into the vein.

She spent more than $100 a day, sometimes traded her prescription pills for street drugs, which led to fentanyl, she said. The synthetic opioid pain killer can be 100 times more powerful than heroin, and is used in hospitals to treat extreme pain.

Fentanyl was found once digging through trash bins at a retirement home. She heard it was sometimes stolen from family or off delivery trucks, and her friend ordered the drug from China off the dark web. Heroin costs $400 a gram in Fargo, fentanyl a lot more than that.

Unlike licensed pharmaceuticals, street drugs aren’t regulated. “It’s like walking into a bar and not knowing if you’re getting 100 proof or a beer,” she said. Trust, in an untrusting world, is hard to come by, and drug dealers in Fargo mix opiates with brown sugar, baking soda, baking powder. “Tons of different baby products, which is really dark.”

She never got caught; her former boyfriend did. “I miss it, I miss the chaos,” she said. “It’s boring sometimes, as hard as it is -- when you don’t have a steady hookup, someone getting raided, someone getting jacked, there’s so many factors, and the thrill of finding it.

“You make so many damn rationalizations. We would do as much as we could handle, which is eyeballing it. And now that I’m talking about it, I’m like ‘Oh my god, I was crazy.’ And it is crazy. You really just come up with excuses.”

Dealers and users order products such as “pinky” U-47700, another synthetic opioid, and fentanyl, over the dark web, and later send them through the mail -- as was the case with “Operation Denial” and “Operation Deadly Merchant.” These were 2015 drug busts led by the Organized Crime and Drug Enforcement Task Force, involving the overdose deaths of five people in North Dakota and North Carolina. Five people were arrested and indicted from North Dakota alone during the operations.

Tens of thousands of people in the U.S. die from opioid overdoses every year, a fact Jackie says is not a deterrent for users, but rather an incentive. Nationally, overdose deaths have surpassed traffic incidents and firearm-related accidents to become the leading cause of accidental deaths, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“That whole scene of the underground, that artistic, dark allure -- that influenced me.” Idols like Kurt Cobain, lead singer of the band Nirvana, who shot himself in the head with a shotgun in 1994, were users. “I was influenced by musicians and artists who I looked up to that did heroin.”

The Opium Wars

Synthetic opioids have also sparked American government and drug enforcement pleas to China for stricter regulations. China has heard the cries for help, but some question if the recent crisis in Fargo and other cities in the USA are not reprisals for the 19th century Opium Wars.

Under the imperial auspices of free trade, Western powers instigated the Opium Wars in China more than a century ago. Today, while trade disputes foment once again, Chinese opium -- though altered -- has reached across the seas to haunt America’s small town streets.

For generations, opium in China was the historical bankroller behind Britain’s power, and the dirty secret behind some of America’s most affluent families. Opium money was the fortune from which Boston’s Cabot family endowed Harvard, and the Russell family promoted Yale’s Skull and Bones Society. It was also the tight-lipped secret behind why U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt did not work a regular job in his life, for his grandfather, Warren Delano, was one of America’s most buccaneer opium dealers in South China.

Now Fargo, incorporated a decade after the Second Opium War, is fighting desperately to stay one step ahead of the dealers. Nationally in 2015 opioid overdoses have taken the number one spot in accidental deaths with a total of 52,404 lethal drug overdoses in 2015, according to the American Society of Addiction Medicine. The epidemic has been driven by opioid addiction through the prescription of pain relievers, and the importation of the synthetic opioids from abroad.

The Center for Disease Control said not only are the deaths alarming, but the financial cost due to loss of productivity reached $20.4 billion in 2013.

“The United States is in the midst of an alarming opioid overdose epidemic and U.S. employers are challenged by the epidemic’s toll on their workers,” the Center for Disease Control reported. In 2015, more than 33,000 Americans died from opiate overdoses, which is nearly quadruple the year 2000.

In other places the powdery killer is known as “TNT,” “Murder 8,” and “Dance Fever,” according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. It is a schedule II drug, and while meticulously weighed by pharmacists when prescribed by physicians, a tiny mistake by street dealers can mean death.

Picture a raisin cut into 500 pieces. One microscopic sliver is the maximum dose of China White a person can ingest without overdosing, Fargo Police Lt. Shannon Ruziska said. He is the unit leader for the Metro Area Street Crimes Division.

A dose is smaller than a pen’s tip, First Step Recovery Agency Director Michael Kaspari said.

The opiate phenomenon in Fargo is now a crisis, Lt. Ruziska said, and the drug comes primarily from China and Mexico.

The drug has torn apart families, friends, and lives, according to local statistics. Out of the 69 overdose calls Fargo Police responded to in 2016, 15 died. Only two overdose deaths were not related to China White, according to Ruziska.

“It surprises me that it’s not higher,” Kaspari, a registered nurse, said. “It’s such a powerful drug. You sit down to veg out on the couch, and you’re going to die. And yet that’s still not a deterrent.”

Fargo is at the “tip of the spear,” as two major highways intersect the city, Kaspari said.

“It’s an easy death, you go to sleep and never wake up. And being dead is not the worst thing that can happen.” An overdose on fentanyl typically slows the circulatory system to one breath per minute, which naturally leads to death, or if saved, to a variety of permanent muscular or mental damage.

“Thirteen deaths, in their mind that’s what the crisis is, it’s 13 deaths, which is tragic, unacceptable, 13 deaths. But I was in a meeting the other day with the state’s attorney… and he said ‘With respect, you guys have no idea what’s going on in the streets,’ and I’m thinking, ‘Geez, we’re up to our ass in alligators here and he’s telling me it’s worse out there?’”

On Christmas Day 2016 alone, one police officer responded to five overdoses, Kaspari said.

Better to keep your mouth shut

Although Fargo Police responded to 69 overdose calls in 2016, many more addicts, fearing criminal charges, were never called in, Lt. Ruziska said.

“I know there are a lot of overdoses that we don’t know about,” Ruziska said. Such as one instance where people administered Narcan -- twice -- before calling 911. Narcan is a nasal spray used for emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdoses. F-M Ambulance and Fargo Fire Department carry Narcan on calls; police officers do not carry the nasal spray with them, but it is available in the evidence processing area, according to Fargo Police Crime Prevention Officer Jessica Schindeldecker.

The user who took Narcan twice survived, but the stigma relating to criminal charges for reporting dangerous drug abuse is something the police department wants the public to know has changed. In many cases, reporting an overdose will not lead to an arrest.

Protected under the Overdose Prevention Immunity Law are those who report and cooperate with officials when an overdose occurs, according to the North Dakota Century Code. Up to three people are eligible for immunity for any one occurrence. In order to be immune, however, the reporting person must remain on scene, must cooperate with emergency medical services and law enforcement, and the overdosed individual must be in need of emergency medical services.

“Some individuals think we are not trying to save lives by doing these investigations and showing up on scene,” Schindeldecker said, “but we can’t save lives without getting these drug dealers out of our community.”

From among 2016’s 69 incidents of drug overdose calls, police obtained eight search warrants to recover evidence, “so we can find out what happened,” according to Sgt. Matt Christianson, head of the narcotics division for the Fargo Police Department. Other investigations occurred in a public place or police received permission to search premises.

“Several” federal indictments of people who sold or delivered drugs to victims, were issued and ten search warrants were obtained, leaving 45 cases where a few were arrested on open warrants, and one person was brought to jail for overdosing three times in four days, Christianson said.

“This is exactly why people don't call the police,” Jackie said.

“Of the remaining incidents, we didn’t arrest anybody or bring charges against anybody on scene, because it either fell under the immunity law or there wasn’t enough evidence to charge them with a crime,” Christianson said.

Jackie said the fear of getting arrested in an overdose situation has not been alleviated in Fargo.

“Why are we just arresting people?” she said. “It is true, the law and the books are there, it’s called the Good Samaritan Law, or the Good Sam Law. It’s been around in other states for many years. People have said that within the last few months that people have called for help from an overdose, but days later they were raided.”

It’s a trick, she said. “It’s failed, the war on drugs has failed. Incarceration costs society more than rehabilitation. Why are we arresting people when they call for 911 because of an overdose? The Fargo Police Department can’t be trusted because they have shown that they care more about arresting people than saving lives They’re not violating the immunity law, they’re searching people days after they called 911.”

Who and where are the dealers?

The Fargo Police Department wants to save lives, and arrest drug dealers, Christianson said. “To me, getting drug dealers off the street does save lives. In today’s culture it is very easy to criticize law enforcement, however… none of us want to see anybody else die before their time from a drug overdose or anything else for that matter. It is very important for us to get in there and get these dealers off the streets.”

Most people don’t deal, they’re middlemen, said Jackie. In Fargo, it’s who you know, which is different from larger cities like Minneapolis where a white girl in a known neighborhood will draw attention, including ready-to-sell dealers. “In Fargo, you have to know a direct person, and even so people are really scared, where in a big city people would just walk up to my window and say ‘Hey, you look like a junkie, do you want some?’ It was faster than McDonalds.”

Dealers primarily come in from outside North Dakota, Christianson said. “They bring it in here, and honestly they don’t care what happens to the people they give the drugs to, all they care about is getting their money.”

Dealers are also hard to pin down. They move from place to place and sell to every layer of society, the poor and the rich. “It really covers all the demographics, it really doesn’t discriminate,” Ruziska said.

While the epidemic is ongoing, and police see little light at end of this “fentanyl tunnel,” Ruziska hopes anyone suspected of overdosing is reported immediately. “Call us right away, you won’t get in trouble. You really are immune, except for those delivering the drug.”

The China connection

The Free Asian Radio Mandarin, a government media outlet, reports Beijing has known of the fentanyl problem, and began restrictions on the sale of fentanyl and the even more potent carfentanil in drugstores and websites nationwide, less than a year ago. In 2016, the China National Narcotics Control Commission announced new regulations pertaining to fentanyl and 18 ingredients involved in manufacturing the drug, called fen tai ni in Chinese, but added that nine months were needed to see any effects coming from stricter policies.

Many companies in China manufacture the ingredients and the actual drug. China is a major producer and exporter of fentanyl, according to a 2017 International Drug Control Strategy Report released by the US State Department.

One company that distributes fentanyl in China is the Hotai Pharmacy Co., Ltd. in rural Hubei Province. The company has sales offices in Guangdong, Shanghai, Henan, Jiangxi, and Shandong, and is listed by the Hubei Provincial Administration for Industry and Commerce as a limited liability company owned solely by Wang Jinyu. It has a registered capital of ¥1 million, which is a comparably low amount for a pharmaceutical company.

Kinbester Trading Co., Ltd., located in the port city of Xiamen, is listed by media outlet Epoch Times as a distributor of a raw ingredient called NPP, used in making fentanyl. The company recently sold 10 kilograms, worth $2,500, to customers in Mexico, and Kinbester employees stated they did not produce the ingredient, they simply sold it. The company has a registered capital of ¥500,000, was established in 2002 as a limited liability company, and is not authorized to sell dangerous chemical goods, according to Zhejiang Provincial Administration for Industry and Commerce.

Another company in Shanghai, China Pharmaceutical (Group) Shanghai Chemical Reagent Company, is one of China’s largest producers and distributors of chemical reagents including fentanyl. The company has a registered capital of ¥45 million and is owned in part by the Sinopharm Group, the largest state-owned pharmaceutical enterprise in China. The Sinopharm Group is riddled with red flags and corruption allegations, including the 2014 arrests on bribery charges of former vice president Shi Jinming, and Zhao Chuanyao, former general manager of a subsidiary of the group.

China began cracking down on illegal fentanyl distribution as early as June 2015, according to government media outlet People’s Network, when custom agents seized 46.8 kilograms of smuggled fentanyl in a Guangdong port. The drug was found inside six boxes containing shoes, clothing, and other personal items, and four smugglers including a customs broker involved in the case were arrested, according to the People’s Network. In February 2016, a fentanyl trafficking ring was broken up in Hunan Province, resulting in the arrests and convictions of three people.

The China National Narcotics Control Commission acknowledges that Chinese companies do manufacture the drug, but that only one-third of China’s products reach American streets, while the remaining two-thirds are smuggled in from Mexico.

On March 2, 2017, the US Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement said during a conference that the United States and China have had a joint liaison group for law enforcement since 1999, and that a resolution will soon be issued under the United Nations Subcommittee on Narcotic Drugs to help curb the fentanyl crisis.

Additionally, the State Food & Drug Administration reported negotiations are underway for US law enforcement officials to help train Chinese drug agencies with investigation techniques into money laundering in relation to the fentanyl and synthetic opium trade, and the Narcotics Control and Public Security Bureau agreed to share information, when possible, pertaining to smuggling secrets.

The Voice of America cited China’s chemical industry’s lack of regulation issues in September 2016, saying that despite China’s efforts to curb illicit sales of fentanyl, the “smuggling of such drugs and their raw materials between China and Mexico still flourish.”

China’s revenge?

Since Xi Jinping’s rise to the presidency and the secretary generalship of China’s Communist Party, China’s propaganda machine has been spinning anti-Japanese, anti-colonialist rhetoric, and has angrily pointed toward China’s embarrassing defeats in the two Opium Wars fought in the 19th century, to incite nationalism. As a trade war looms between China and the Trump Administration, some think America’s fentanyl problem may be retaliation for the Opium Wars, little-known conflicts nearly forgotten by the West.

“I’m not necessarily espousing this but when you think about it, it makes sense,” Kaspari said. “I have heard people primarily in law enforcement talking about bio-terrorism, that one of the reasons this is being pumped out of China and into our country is with a bio-terroristic intent. Can I point to it and say there’s any hard evidence? No. But if it looks like a skunk and smells like a skunk…”

Authorities in America can do little but watch, Kaspari said. “We can see when a shipment of carfentanil hits Chicago. We can see it move across the county and then it hits Minneapolis/St. Paul, and then we know it’s on the way because there’s a spike in overdose deaths.

“And then it hits Fargo and, boom,” Kaspari snaps his fingers. “We have three overdose deaths. It’s coming into the country in bucketloads. A kilo of it is worth I think $1,200, and has tens of thousands of doses. It’s like a wave coming across the country when a new shipment comes in.”

“Fentanyl is not the devil, it’s a miracle drug for severe pain management,” Kaspari said. “It’s a beautiful thing.” Longtime use of it builds a tolerance, however, and could be addictive if hospital personnel are not trained properly.

It’s hard to get help

In the past, police have not known how to deal with addicts, leaving two choices, the emergency room or jail. The single biggest complaint is that suffering people do not know who to call.

Fargo Cass Public Health Substance Abuse Prevention Coordinator, Robyn Litke Sall, said that Fargo has a “social detox” center, a place where someone can sit and be monitored until ready to be brought home.

Across the state border, however, the Clay County Detox Center has doctors, nurses, and medication, and differs from Cass County’s “drunk tank.” Historically, Fargo has shuffled addicts across the Red River for help, Kaspari said.

“That’s one very big roadblock for people who want to enter treatment, because they have to go through detox in order to get into treatment and participate in that project and unfortunately there isn't really anything here that can help them go through that difficult process that would get them ready to go to treatment,” Sall said.

The Treatment and Recovery Group is working on expansion of facilities, Sall said. Emergency room detox is also currently not available, and such services are not reimbursed through insurance companies.

“The main problem in Fargo is that we do not know how to help people coming off heroin,” Jackie said. “We don't offer methadone or suboxone for detoxes, which help alleviates withdrawal symptoms and reduce cravings.”

Addicts are welcome at the First Step Recovery, for starters, Kaspari said. First Step Recovery is a nonprofit organization and a part of The Village Family Service Center, established in 1891. The center treats alcoholism and addictions as a disease.

Under the Mayor’s Blue Ribbon Commission, politicians and authorities from Fargo, West Fargo, Moorhead, Dilworth, and Horace, are pooling resources to battle the crisis. A cocktail of medications is already available to ease the symptoms of drug or alcohol addiction, but additional services are forthcoming -- within weeks, Kaspari said.

“A lot of our perceived holes in our system are just that, perceived,” he said.

“I’ve been to a lot of these types of workgroups, and all they’ve ever done is talk about the problems,” Kaspari said. “The first meeting when I saw who was attending, you could have knocked me over with a feather.” Everyone at the table was asking what their roles were, he said.

Substance Use Disorder Vouchers are also available to help those dealing with addiction, according to the Fargo Police Department. Year-long treatment programs are focused on accountability and are known as Drug Court, and if successful can remove charges from a drug offender’s record.

“It often takes several attempts at treatment to make it work, that’s not lost on us, we do our best to try and help people get down that road,” Christianson said. “We are a starting point for people to get help. We’ve had people call us and say ‘Hey, thanks for arresting me, I know I wasn’t nice to you at that time it happened, that really turned my life around.’ That doesn’t always happen, but there are certainly cases where that is the case.”

Jackie accepts that her addiction is life-long, and is using non-traditional methods to keep herself clean.

“The statistics are abysmal,” Jackie said. “I don’t even like to look into that too much because most people end up dying or going to jail.”

Under 10 percent succeed, she said, which is a hard statistic to prove, but it’s the number stuck in her head.

“I’m just starting to deal with all the bullshit of life again.” The daily grind is what can wear down resistance. “I detoxed for a few days in the hospital, but I left, or I would have gone insane.

“For me, I had to cut toxic people and active users from my life and reconnect with family and friends.

The main thing is build a life worth living, build things that build your community, part of it for me is giving back.”

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

January 16th 2026

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)