News | September 11th, 2019

WILEY FIELD, North Dakota – The stench hits first. Invisible and explosive, hydrogen sulfide burns through mucous membranes, leaving a metallic taste on the tongue. Breathe in enough – which isn’t much – and the gas, a byproduct of crude oil, will knock down anyone within two breaths. Death comes in minutes.

With few signs of burning flares on a windy day, the invisible poison has no ground zero in the oilfields of Bottineau County. It can be smelled everywhere between the “nodding donkeys” and endless rows of corn, wheat, soybeans, and canola.

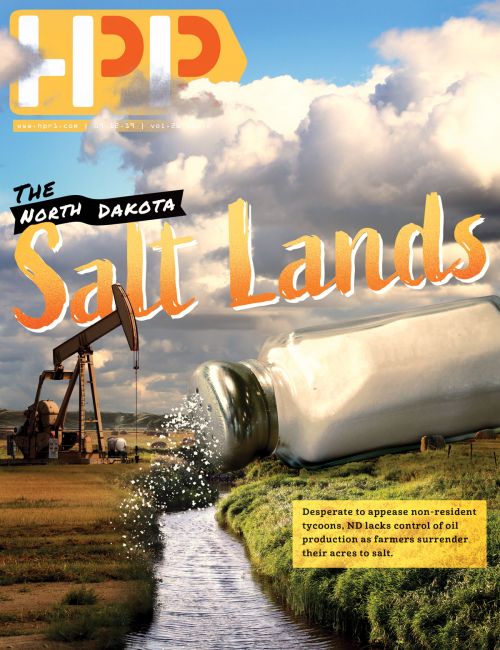

Salted land-scars from recent brine spills and older Legacy-era evaporation pits pockmark fields. Acres upon acres are barren, littered with scorched earth, rusted oil and brine tanks. Barrels filled with waste, some labeled with biohazard warnings, are strewn haphazard, dumped illegally.

Daryl Peterson, a retired farmer who has been fighting the current system for 25 years, knelt into a sandy, discolored section in the Renville Township road ditch. Pooled water nearby was covered in a sickly sheen. He pierced the earth with an EC or electro conductivity meter to gauge the salinity level. “Out of range,” the meter reported.

Another section was more than 13 points higher than healthy soil should be.

“Game and Fish gives out a reward for reporting a poacher, and yet I’ve been tarred and feathered,” Peterson said. “I support responsible oil production but it’s not being done. Our land is in great jeopardy. This is a never ending battle.”

For 25 years, Peterson has been trying to warn the state that too many spills are underreported or are not reported by oil operators at all. He’s given dozens of tours to politicians, concerned citizens, even a trip with Governor Doug Burgum to inspect the area. Oil lobbyists insist on attending some of the larger tours, and one response he hears quite frequently is that the devastation in Bottineau County stems from the old Legacy days, when thousands of brine pits were dug to store poisonous saltwater.

Nothing could be further from the truth, Peterson said. “We call those ‘the sins of our fathers,’ With all this damage out here there is a cost. There are lands that won’t qualify for a mortgage.”

Legacy wells are frequently used as an excuse for land contamination on spill reports, but there are no salt pits or Legacy spills in Renville field.

Worthless land

Daryl Peterson has 720 acres worth approximately $2,000 an acre, but unless a buyer assumes liability, it is worthless.

In 2015, the Chief Executive Officer of Farm Credit Services of North Dakota, Claude Sem, testified before the House Natural Resources Committee warning the state that many farmers across oil-rich North Dakota will have tremendous difficulty leasing land.

“Farm Credit is concerned about taking security in any property that has or potentially has hazardous materials on the premises, such as from a saltwater spill or oil spill,’ Sem said. “In fact, we would be cautious of even taking collateral near the hazardous or potentially hazardous site. It is and has been the policy of FCSND to not take security in property that is or potentially will be environmentally damaged. FCS discourages credit applications on property that is contaminated and would, and will, deny approval if credit was requested.”

Few farmers in rural North Dakota dare to stand up to the state’s Industrial Commission, oil promoter and regulator, and the big oil lobby, but neighbors privately thank him for his courage, he said. In uncertain times for farmers, mineral rights royalties help pay the bills.

“North Dakota has great rules on the books, but they’re not enforced,” Peterson said. “The Health Department is doing a very inadequate job of cleaning up spills and overseeing the cleanup. They’re going to leave a scar in North Dakota. Our land, water, and livelihoods should not suffer because of the economics of oil production.”

Bismarck land and mineral rights attorney Fintan Dooley created the Salted Land and Water Council, Inc. to help farmers monitor the conduct of state government and oil companies. “We want to find remedies for land and water damages,” Dooley said.

He chose the name to recall Rome’s conquest of Carthage. At that time Roman General Scipio Africanus salted Carthage’s lands so Carthage would never rise again.

“As a consequence of the ignorance of our public officials or their willingness to look the other way, we have salt pits all over the Williston Basin, thousands,” Dooley said. “We don’t even know where they all are. Ground Zero is Bottineau and Renville counties, and the plume of death overlaps into Ward County.”

Salt from the pits – known then as evaporation pits from the 1950s and 1960s – have leached through the clay berms and destroyed farmland.

“Until and unless massive amounts of money and effort remove – that is dig and haul salted soil – or tiling allows soil washing and brine capture then pumped into the Dakota Formation, farmers will be prevented from the raising of crops for decades,” Dooley said.

In addition, solid waste such as radioactive socks and other refuse is being generated and stored illegally in the Bakken, Dooley said.

“In Mohall, even after companies were warned to clean up illegal dumps, the state’s Department of Health filed no charges,” Dooley said. “Daryl Peterson declares no changes were made to disposal areas. There are ineffective and incomplete makeshift berms around the barrels on the North Side of Mohall; and in more rural sites, no berms appear to have ever been created.”

North Dakota’s Administrative Code related to disposal of hazardous wastes mandates that all materials used in exploration and production of oil and gas are to be disposed of in an authorized facility.

“The Mohall and rural junk yards are not authorized facilities,” Dooley said.

Fighting such cases in the courts is as difficult as removing tons of earth, Dooley said. Peterson settled his case in court, but at his own expense.

“Solo litigation is an unbalanced affair,” Dooley said in a Prairie Pulse interview with NPR. "Try taking on Harold Hamm. The Wall Street Journal said he bought North Dakota. What if his company spilled salts and ruined your land? Try suing him.”

Repairing the earth is also a timely and costly affair, Dooley said.

“Brines in the Williston Basin are ten times saltier than seawater. Ten times,” Dooley said. “It will kill everything, and the only way to get life back in the soil is to dilute it. That means you have to wash the soil and you have to replace some of the components in the soil that are missing, calcium for one.”

Into the lion’s den

State auditor Josh Gallion met with Peterson and Dooley in late August to talk about a potential audit of wells in the oil fields.

“We do not have the skill set or the capability to do that,” Gallion said. “To really dig into that issue we would need to go to the North Dakota Legislature to ask for permission.”

“I don’t think you have to dig very deep in order to find something really smelly here,” Peterson said.

“We are severely undersized,” Gallion said. “I want the least government possible; we want a light touch, but I don’t work for the governor, I don’t work for the legislature. I work for the people of North Dakota.”

Fifteen years ago the state had a budget of $5.5 billion, Gallion said. Today, his agency has 58 employees to keep track of the state’s $14.7 billion budget.

“And we are still expected to do the same work,” Gallion said. “We audit and we look at less and still we are doing enough to piss off a lot of people.”

Peterson stood up to offer Gallion a challenge: “I think you’re selling yourself short,” Peterson said. “I think you can do a lot more than you think you can.”

“I accept your challenge,” Gallion said. “Nobody loves a tattletale except for us.”

Gallion was elected to be North Dakota’s eyes and ears. In his first term, he has already ruffled feathers with his audits of the Governor’s expenditures and other issues so much so that politicians clipped his wings through legislation; now he has to receive permission for most audits. He isn’t afraid of performing an audit of oil-producing wells, but he wants it done right, he said. He’s diversifying his office’s skills, and when ready – with permission – will perform an audit on oil production in the state, he said.

When that day comes he offered a warning: “If you’re going to send me into the lion’s den, please, pray for the lions.”

What is life worth?

In the oil fields, a human life is worth about $1.6 million and change, or so said U.S. District Judge Daniel L. Hovland when he ordered C&J Well Services to pay restitution for the death of a worker, Dustin Payne. Payne, 28, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran of campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, was welding an unclean tanker trailer on October 3, 2014 that had saltwater remnants left inside. The tank exploded and Payne was fatally injured.

But what of the life of the land?

The state’s regulatory and environmental departments have come under criticism lately for under-reporting spill volumes and for not allowing inspectors to update critical information . A 2018 deposition of the state’s Industrial Commission’s director Lynn Helms shows that spill volumes are not the state’s priority. The ONEOK natural gas processing plant in McKenzie County – originally reported as a 10-gallon condensate spill - has so farfound846,000 additional gallons.

“Accuracy with regards to volumes is not – not the Number One priority,” Helms said in the deposition. “Action is the number one priority. So I’ve sometimes compared it to a 911 call. How many people are there doing CPR is not relevant at that point in time. The address and the condition of the patient – and getting the right resources there are. It’s acceptable, but it’s not great.”

Since 1975, the North Dakota Department of Health reports approximately 9,710 spills in oil country, with 2,932 under the state’s Department of Environmental Quality jurisdiction of which 546 areas are under remediation.

Many spills go under-reported, as investigators initially rely on information provided by oil operators, and there are spills that are reported late without penalties. Spills that don’t get reported exist as well.

Carl Rockeman, the director of the state’s Division of Water Quality, agreed with Helms: spill size does not determine his agency’s prioritization of spills, he said.

“I would rather receive a timely report with limited information known at that time than have to wait weeks, months to have a more accurate estimate and delay that response,” Rockeman said. “Timeliness is more important to me than having an accurate number.”

Saltwater that comes from oil wells is 250,000 parts per million of salt, a thousand times saltier than tap water, he said.

“There’s really not a simple mathematical add-up-the-numbers calculation,” Rockeman said. “To determine the spill volume afterwards is very difficult. I would say typically it’s no more than a good guess if you’re only looking at things after the fact. As far as how important, it’s really not one of the driving factors that drives the cleanup process. What we look at during the cleanup process is concentration. You can have a very small volume of spill that can have a large impact depending on the concentration or the area it’s in or you can have a very large spill that is contained in a small area that can be less of an impact.

“Volume is not the best indicator of impact.”

The first rule on the North Dakota Department of Health Environmental Health Section Division of Water Quality’s site assessment protocol is to “estimate the volume of saltwater released,” “estimate the volume of saltwater not contained within a well pad,” and “document the area of impact.”

ONEOK’s Garden Creek I Gas Processing Plantspill could potentially reach 11 million gallons of “liquid gold” or condensate, according to an internal memo from ONEOK Partners. If that amount was reached, the spill would be considered one of the largest in history, or at least in America.

Out of the 15,741 operating wells in North Dakota this past June, four spill cases near the Renville field in Bottineau County were chosen for investigation. Online reports state or imply zero barrels spilled, but the math disagrees. Thousands of barrels of brine, in one case enough to fill 10 Olympic-sized swimming pools, are missing.

Cramer 1 SWD

July 14, 2011: Farm operator Matt Peterson was spraying Round-Up in Renville field near the Cramer well when he saw dead vegetation and salt crystallization around several ponds in the area. A week later, Ben Tohm, a Petro Harvester Oil & Gas, LLC foreman, reported a hole in the pipeline from which 300 barrels spilled into the ground.

The pipeline was shut down. A dike was built, but the spill had already spread across 23.8 acres, poisoning ten surface water ponds. Three months after the reported spill, Petro Harvester removed 52,861 barrels of contaminated water from the heavily impacted ponds.

On July 21, 2011, the North Dakota Industrial Commission Oil and Gas Division issued a statement saying no follow-up report was required.

The Cramer spill of 2011 initially was reported at 300 barrels of brine, but in actuality 135,547 barrels were spilled between May and August 2011, and is perhaps the largest brine spill in North Dakota.

The actual spillage was downplayed, but by 2017, cleanup company Kleinfelder Inc. reported to Petro Harvester Operating Company LLC, the area operator, that they had pumped in excess of 49,300 barrels of contaminated dissolved fluids and 27,630 barrels of chloride out of the spill zone. (Contaminated fluids and chloride are in brine).

Renville field has only two saltwater disposal wells, whose job is to inject water into the earth to push oil toward working wells. From April until June, a total of 1,587,808 barrels of water were injected into Renville field, according to state records.

During that same time the Cramer 1 SWD well had a massive spike in saltwater disposals months prior to discovering the leak. In 2010 the well disposed of an average of approximately 44,553 barrels of saltwater per month, but in November and December 2010, those numbers jumped, then skyrocketed in June 2011, the month the leak was discovered, to 170,262 barrels.

The second nearby disposal well in the same field, the Rice-State 2 H, disposed of 392,437 barrels of brine during the same period.

Add and subtract the totals and the brine disposals from Renville field fell far short of the amount inserted from May until August 2011 – before and after the spill – meaning 135,547 barrels of brine went missing.

Eight years after the 2011 spill, plants still struggle to grow. Salt crystals form in the sunlight. Bare spots plague the fields.

Numerous spills have been reported from Cramer 1 SWD since it was drilled in 1997, and the state’s Industrial Commission approved operational ownership transfers at least three times without ensuring the land was remediated.

Critics claim the transfers of polluted land and abandoned wells are a racket, a “rob Peter to pay Paul” scheme against unsuspecting new companies with “oil rush” mentalities who fail to do their due diligence.

Peterson’s wells

After numerous brine spills and large sums of money spent trying to get his land cleaned in Bottineau County, Daryl Peterson took oil operators, Sagebrush Resource, Ballantyne Oil, and Petro Harvester Operating Co. to court in 2014. The North Dakota Industrial Commission and the Oil and Gas Division became unnamed parties in the case, which strived to prove that all the defendants failed to remove contaminants from his land.

For years, Peterson petitioned the state to clean up his lands and replace topsoil, but his requests were ignored until 2011. After the cleanup, he was still unable to grow vegetation because of continued saltwater contamination, he said.

Oil companies insisted the area was clean; the state of North Dakota backed their claims and took an adversarial position against Peterson’s claims.

“They [NDIC] sided with the oil industry for three years, then later admitted a proper cleanup was not conducted,” Peterson said. “The facts were all there. The big picture is: Is that going on everywhere? My best guess is that it is.”

“The bulk of the damage is not Legacy, it is spills since then,” Peterson said.

Peterson’s attorney, Derrick Braaten, held depositions with Lynn Helms, and Dave Glatt, director of the Department of Health, and ended up settling the case, and cannot say more due to settlement agreements except to say: “We appreciate Petro Harvester commitment to restore our land. They’ve cordoned off 60 acres to determine where the contamination exists.”

In Peterson’s lawsuit, a foreman at the time for Petro Harvester, Ben Thom, said while working for the company on Peterson 2 well, he would notice bare spots where plants wouldn’t grow, but never felt inclined to report the findings.

“Typically a spill will – a spill of any sort will kill the vegetation around it,” Thom said during deposition. “If there was massive dead spots in the middle of a lush, green area, I would probably notice.”

“Would you follow up on that at all?” asked Braaten, an attorney with Baumstark Braaten Law Partners.

“Probably not unless asked to.”

“And who would ask you to do that?”

“Typically a landowner.”

“Anyone else?”

“Usually just at the request of a landowner that I can think of.”

Company policy at the time that Thom worked for Petro Harvester was to over report a spill, not under report, he said. Spills, once discovered, were typically reported within 24 hours.

“In the initial spill report we’re not so worried about making an accurate estimate of the spill volume,” Thom said. “We’re more concerned with getting the problem solved, you know, the corrective action so it doesn’t happen again and getting the spill cleaned up.”

In the dead of winter, some spills are left alone to wait for spring. Oil spills are at times sprayed with hot water, pushing the contaminants and melting snow into a collecting point to be sucked up. Gravel is also used to “soak up” brine. Several spills on Peterson 2 well were simply excavated, and no conductivity meter readings were performed to check the salinity of the soil.

On Peterson’s land, some spills went unreported, deposition records indicated. Hot brine was used on at least one occasion to melt snow, and gravel was used to cover up dried salt on the ground, according to Thom’s deposition, taken on October 9, 2018. Both instances would be considered a felony according to North Dakota Industrial Commission’s regulations.

“Illegal transportation or disposal of radioactive waste material or hazardous waste means the transportation or disposal into a nonhazardous waste landfill or the intentional and unlawful dumping into or on any land or water,” according to the North Dakota Century Code.

During Thom’s deposition, Braaten grilled him on a series of contaminated water and oil extractions from one of the spills on Peterson’s land.

“I think we talked about this earlier, but they’re indicating that they heated the salt water in order to wash up the oil from the spill; is that right?” Braaten said.

“I don’t know if they’re -- I don’t know what they were doing,” Thom said. “They could have been washing out a mud tank. I don’t know.”

“Well, on the other ones -”

“True enough.”

“They say wash out mud tank.”

“Right”

“This one says was spill.”

“Yeah.”

When shown pictures of a white substance on soil near Peterson’s spill area, Thom acknowledged that it resembled salt. To the side of the white substance stood piles of gravel.

“Do you know what those piles of gravel there were for?” Braaten said.

“I assume they were using it as a bit of floor dry to try and soak up some of the water,” Thom said.

“Or to cover up the salt?”

“Could be.”

Spill reports are also sometimes not reported when they are related to an earlier spill, such as fresh water mixing with brine or oil that leaked offsite, Thom said.

Changes to spill reports are not common knowledge to oil workers, Thom said. When a report about a spill stated that contaminants remained on site, he disagreed, but did not change the information on the report filed with the Health Department or the Oil and Gas Division, he said.

“I guess the way I understood the spill report is once it’s filled, the information that’s on it is there,” Thom said. “I wasn’t aware of how to correct an existing report once it’s been filled.”

Haugen B CTB well

June 6, 2014: A pump malfunction at the Haugen B CTB well leaked 700 barrels of brine into Wiley field wetlands on June 6, 2014. Investigators reported they did not know the amount or type of release. No one knew how much spilled outside the dike, but investigators later upgraded their assessment saying at least 1,000 barrels had leaked out.

Official reports still report zero barrels spilled. Little effort was done to clean up the area, and the company was released from all liability, according to spill records.

Two years later and after cleanup, investigators became concerned with surface water samples reading elevated chloride. By 2018, investigators partially blamed historical evaporation pit issues in the area, but recommended “no further work” was needed.

Three months before the June 6 leak, a different pipeline connection broke at the Haugen A-1 well, also in Wiley field, which spilled one barrel of oil and nine barrels of brine that remained on location, according to state records. According to inspectors, who primarily depend on information from operators, all of the leaked materials were recovered. The area was washed with heated fresh water, and yet today, acres surrounding the well are barren.

The list of owners behind Haugen A-1 is also long: from Denbury Onshore, LLC, to Kerr-McGee Oil & Gas Onshore, LP, to Encore Operating, L.P., to Scout Energy Management, LLC. On April 23, 2013, one barrel of oil and nine barrels of brine spilled from a piping connection leak, according to state records. All of the leak was recovered; the area was washed with heated fresh water.

The state’s Industrial Commission determined there was no immediate risk, and no follow-up report was requested.

The company responsible for the spill, Denbury Onshore, LLC, received a “Get out of spill free card,” Daryl Peterson said.

“It’s at least 1,000 barrels, and that 1,000-barrel spill has been forgiven,” Peterson said. “That company spent zero dollars, and now Scout [Scout Energy Management] has it and they’ve been doing all these studies on how to clean up these historical spills.

“It’s all smoke and mirrors, and they know they can’t clean it up,” Peterson said. “My problem is that there have been hundreds of spills in Wiley field since the evaporation pits and hardly any of them had any real cleanup.”

Leo Hallof 1

August 9, 2013: A “flowline” leaked between a tank and the Leo Hallof 1 injection well for more than 24 hours, according to state records. Initially, operator Murex Petroleum Corporation and the North Dakota Industrial Commission reported zero barrels leaked, but that saltwater had poured into a nearby slough, which later covered at least one acre of farmland. Testing with conductivity meters reported salinity was out of range, and then heavy rains commenced, slowing work for days.

Official reports still equate zero barrels spilled.

Some excavation occurred before winter set in, contaminated soil was removed and replaced, and investigators returned in the spring. Further ground testing showed some areas had improved, but little was done in 2014. Inspectors returned in October 2015 and discovered cover crops had mixed results. By 2017 soybeans would not grow near the impacted area, but investigators said there was little sign of contaminants.

In the end, the North Dakota Industrial Commission said an accurate estimate of brine spilled at Leo Hallof 1 was 5,000 barrels, and like the Charbonneau Creek spill in 2006, which leaked more than 23,000 barrels, the spill involved surface and ground waters.

Leo Hallof 1 also had repeated leaks, in 2006, 2005, and in 2001, while it was being operated by B&B Oilfield Services out of Louisiana, according to state records.

‘It’s those relationships’

In one form or another, Lynn Helms has been the director of the Industrial Commission’s Department of Mineral Resources, which includes the Oil and Gas Division, for more than 21 years. He used to work as an engineer for Texaco and Amerada Hess, now the Hess Corporation, in Williston.

Helms’s job “pretty much cover[s] the whole realm of – of everything in the oil and gas world,” according to his own deposition taken on November 5, 2018 in the Daryl and Christine Peterson vs. Petro Harvester Operating Company, LLC civil lawsuit. Helms’s purpose is a “dual mission of both an oil industry promoter and its chief regulator” in North Dakota, according to the Western Values Project, a public charity sponsor working toward responsibility on public lands.

By Helms’s own admission, the state does not have enough inspectors to cover all the spills across the state, and the size of a spill does determine response, according to his deposition. Working relationships between operators, landowners, and the government is one based on trust. When spills are reported investigators typically base the importance of the incident on information from oil operators, Helms said.

“Hmm. I think it depends on their relationship with the oil and gas operator, primarily, and then, secondarily, their relationship with our field inspection staff,” Helms said. “So some people want to be very involved and cultivate those relationships and contacts and others not so much. But like everything in North Dakota, it's those relationships.”

Although the state has guidelines pertaining to salted lands, only three state employees are responsible for approving plans – typically created by oil companies – for soil remediation, Helms said.

No one employed with the Industrial Commission Oil and Gas Division or the Department of Health are hydrologists, scientists that specialize in water, or agronomists, experts in soil management and crop production, Helms said.

Salted lands

Salt pits – known then as evaporation pits from the 1950s and 1060s – have seeped through the clays and have destroyed farms from ever raising crops again, unless massive amounts of money and effort replaces the salted soil, attorney Fintan Dooley said.

The Salted Lands Council has repeatedly discovered through aerial photographs evidence that multiple companies are also improperly disposing of toxic and radioactive waste in North Dakota oil fields. Even after companies were warned by the state’s Department of Health, no changes were made to disposal areas, which are effectively barrels stacked together on a plastic trap. On some sites a makeshift berm was created around the barrels, and in other sites, no berms were created, photographs showed.

North Dakota’s Administrative Code related to disposal of hazardous wastes mandates that all such materials used in exploration and production of oil and gas be disposed of at an authorized facility.

“No saltwater, drilling mud, crude oil, waste oil, or other waste shall be stored in earthen pits or open receptacles except in an emergency and upon approval by the director,” the state’s Administrative Code stated.

All surface tanks and production equipment must also be devoid of leaks and resistant to the effects of the contents inside, but unused tanks must be removed from the site in less than one year, according to the state’s Administrative Code.

In Bottineau County, numerous areas contain barrels labeled with toxic warning signs. Rusty tanks and unused equipment have been sitting in farmlands for years.

“Oil industry’s salted and junk piled lands got to have a Three-Phase Evaluation,” Dooley said. “Phase one: I’d look at it and list your concerns. Phase two means do testing. Phase three is go at it. In the oil patch you dig and haul what is radioactive. If salty, tile and wash. Then add calcium, and there are many other amendments to bring life to the soil.

“What the oil industry has abandoned needs money or Jesus to resurrect what Harold Hamm’s despoiled Oklahoma farmers call ‘Dead Soil.’”

“Much of the contamination in rural North Dakota seems to be migrating under and off of well sites caused by contained spills that are not verified cleaned up by independent testing,” Daryl Peterson said. “It’s like cancer moving out.”

YOU SHOULD KNOW:

The Salted Lands Council will be holding a conference starting at 5 p.m. on October 21 at the Heritage Center in Bismarck and on October 22, 2019 at the BPS Career Academy on 1221 College Drive Bismarck from 8 a.m. until 5 p.m. Bismarck land and mineral rights attorney Fintan Dooley welcomes photos and reports of suspected violations. For information email saltedlands@gmail.com or call (701) 212-1000.

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)