News | October 30th, 2019

MANDAN — A lone activist delivering a yurt to Dakota Access Pipeline’s protest camps came close to challenging civil asset forfeiture laws, but the state, at the last minute, declined to defend the law in court.

Aaron Dorn, a former National Guard soldier from upstate New York, never intended to stand on the front lines or get arrested in 2016 while Standing Rock and thousands of others protested Energy Transfer Partners oil interests. He simply wanted to deliver a yurt and supplies, stay a few weeks, and go home before the long prairie winter.

But it was not to be. On Thanksgiving Day he set off from the camps to continue constructing the yurt he brought, but got caught up in a caravan heading to Bismarck, he said. Law enforcement said he later tried to obstruct officers while driving on a 25 mph road, but the video footage shown during trial proved otherwise. His truck and all his possessions were seized. He was arrested while most of America ate turkey and watched football, spent the night in jail, and was released on $5,000 bond.

Written testimonies from officers with the Beulah Police Department, Bureau of Criminal Investigation, and the Bismarck Police Department state that Dorn attempted to push a marked police car off the road with his vehicle.

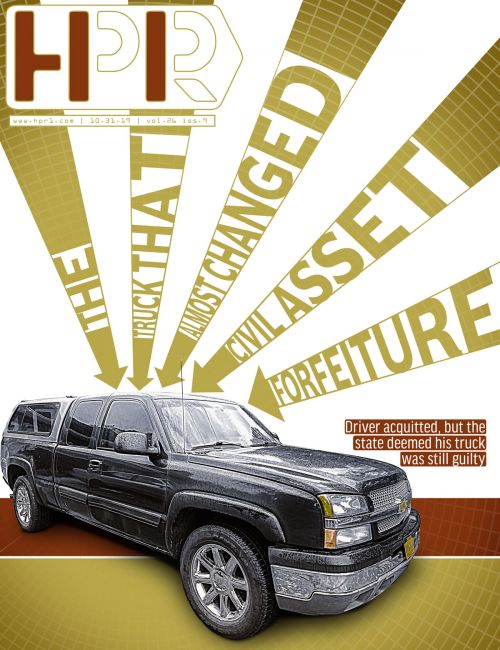

Dorn, 35, was acquitted of all charges, but Assistant State’s Attorney Gabrielle J. Goter still wanted his 2003 Chevrolet Silverado, worth less than $5,000. Stating that the vehicle was used to commit a crime during the DAPL protest, the state began civil asset forfeiture proceedings.

Many of Dorn’s personal items were confiscated along with his truck: his passport, Social Security card, driver’s license, clothes, a cell phone, camping equipment, and he lived like a homeless person for a month. He fought an uphill battle until October this year, when the state backed away from its case, and after nearly three years Dorn drove his car home.

His car’s condition — with 120,000 miles on it — was terrible, he said. Mice had eaten through wiring. Flat tires. Door handles ripped off. Power steering box was leaking, but the engine started up after a full tank of gas and a fresh battery.

“It was my father’s truck,” Dorn said. “He passed it on to me. I’m elated to get my truck back. I was an antique salesman, and I used my truck for everything. Before that I used it in the construction business. When I lost my truck I borrowed a little Toyota to take my daughter to preschool every day. Now that I got my truck back I can slowly pick up the pieces of my life.”

Dorn emailed every attorney in North Dakota before and after trial. No one responded. He kept fighting for three years and lost his home because he could no longer afford payments.

“The prosecutor threw in the towel and said I’m not going to fight this,” Dorn said. “That’s a very horrible thing where the prosecutors get to keep the unjust tools. That’s the problem with this case. People say I won, but I really didn’t.”

According to North Dakota Highway Patrol dash cam footage, Dorn was targeted by a trooper named Michael Arndt.

“This guy’s going down,” Arndt stated in police dash cam footage, a few minutes before taking an illegal left turn from the center lane. “We’ll get him separated and we’re taking him.”

“They were going to try and paint me as some eco-terrorist,” Dorn said. “It’s been hard. I didn’t have anybody to buy me a new truck. I’m a self made man, I make money with my truck, without it I was left at home and for three years I was preparing for a criminal trial, I had that hanging over me.”

He chose to help during the Dakota Access Pipeline controversy because he believes in protecting free speech, and doesn’t want future generations to go through what he did.

“I’m out risking my butt so my daughter doesn’t have to,” Dorn said. "Your right to protest is the same right that should be given to every other person, it doesn’t matter what your beliefs are. We have to protect that right for everyone. I want my daughter to be able to do that. It’s the foundation of a democratic country.

“When it comes to standing up for what’s right, I’m never going to back down.”

“Aaron’s case is an important check on states who would use forfeiture to take people’s property with no good basis for doing so,” Dorn’s attorney Michael Francus said. “The outcome here will help ensure that states abide by constitutional protections instead of cutting corners to take assets and property from people who have done nothing wrong.”

This past legislative session Representative Rick Becker, a Republican of Bismarck, proposed changes to North Dakota’s civil asset forfeiture laws. He sought transparency in reporting forfeiture cases, wider disbursement of forfeiture monies, and to allow the forfeiture of property only if a suspect is found guilty.

The bill that passed was a watered down version, he said. Law enforcement showed up in force and in uniform — an “intimidating” tactic — he said, to push for a different version during hearings.

“The state can’t take your property,” Becker said. “That’s starts right off the bat. Presumably they can take it if it was involved in a crime, but you have the added issue of taking of property that can lead to a penalty greater than that prescribed by law. It’s a double whammy.

“Reporting is allegedly reformed, but it’s a joke,” Becker said of the bill that passed. “Second is the neutral fund, now each municipality will have its own fund and if law enforcement wants monies they ask the municipality. I guess it’s an extra step. The real reform would put it into a state school fund or another fund, now all they have to do is instead of going straight to their fund they go to the district or the county. That’s pseudo reform.”

Becker is a fierce proponent of civil asset forfeiture laws changing, he said, and the current political climate’s pendulum is swinging toward reform. His research shows that the majority of civil asset forfeiture cases in North Dakota come from low stake property worth under $1,000. Even more worrisome is that most people typically don’t fight the state on such civil asset forfeiture cases, he said.

“Dorn is the exception,” Becker said. “Inherent in what happened with Dorn is the issue of civil asset forfeiture altogether. So much of it is with low stake property. If you got a beater of a car worth not more than five grand you’re not going to fight it, and the state gets to keep it. We have to follow the law. If he was acquitted, then that’s not guilty. If he’s not guilty he should get his property back.”

Becker considers the reform bill that passed last legislative session an overstep and overreach by law enforcement.

“But I blame the legislators because law enforcement is doing what they can to get what they want, but the willingness of legislators to acquiesce is amazing. Law enforcement tells the legislature jump, and they ask how high.

“We all have different jobs and it’s okay to disagree,” Becker said. "This idea of you can’t disagree with law enforcement or you are anti law enforcement is insane.”

Dorn said police lied in his case, saying he acted threatening, but he was drinking coffee outside of a Burger King, trying to shuffle away from the front lines when a van pulled up.

“There were three guys in it and they looked mean as hell,” Dorn said. “They get out of the car and they zeroed in on me. I threw up my hands and said, ‘Hey, get back.’ They had guns on their hips, had no markings, and they were wearing ski masks.

“I was backing up with arms outstretched, and they ran toward me and grabbed my arms and dog piled me. Then the police formed a line in front of my arrest to separate me from the protestors.

“They knee-ed me,” Dorn said. Written police testimony confirmed that Dorn was knee-ed at least multiple times. “This cop full force kneed me in the rib cage, two or three times. They were slamming my head on the ground, kicking me, all kinds of stuff. I don’t have any bad feelings toward the cops, but they said I was trying to kill one of their own, and I understand that. One of these cops tried to say I was reaching for a gun on a cop’s hip.”

Dorn doesn’t regret fighting for both his freedom and his Chevy Silverado. The car symbolizes freedom to Dorn, a lifestyle of camping and hiking throughout the United States and Canada.

“Civil asset forfeiture in my opinion is unconstitutional - any part of it,” Dorn said. “Any time a government - it goes back to checks and balances - the government has way too much power and then to seize citizen’s property and you have to prove that your are innocent? Basically you should not have to prove that your property is innocent, it should be the other way around. Right from the outset, police officers make accusations and they get to take your property? And then you have to prove your innocence? That’s insane.”

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)