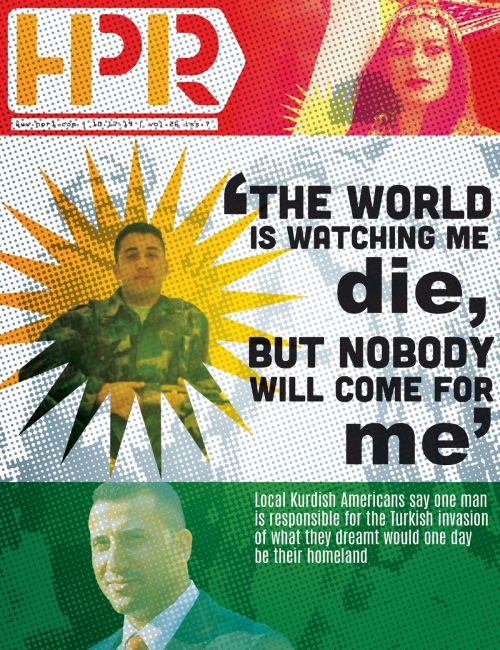

News | October 16th, 2019

MOORHEAD - As a young boy growing up in Kurdish-controlled Iraq, Jahwar Salih played soccer and tennis, dreamed of a college education. Those dreams were smashed after he turned 16; he picked up an AK-47 and joined the Peshmerga to fight Saddam Hussein’s attempted genocide of the Kurds.

Even as a child the threat of extinction was never far away. Chemical gas attacks and superior war machines kept his people on the run. Hundreds of thousands died. Today, after beating the terrorist organization known as ISIS and securing the northern section of Syria, Salih’s people are on the run again after President Donald Trump essentially green-lighted Turkish aggression against the Kurds.

The Kurds are an ethnic group numbering approximately 40 million, but are primarily located in four areas of the Middle East. They’ve been without a true homeland for centuries. Historically, the Kurds have been U.S. allies in the Middle East. They were the first to fight Hussein’s regime, and the first to fight and later beat ISIS.

"My entire life my family has gone from bunker to bunker to try and escape Saddam Hussein’s genocide and before I was born it was the same thing with my parents and my grandparents,” Salih said. “There have been centuries of this, in all the areas of Kurdistan. The Kurds have been a part of a genocide forever and it seems nobody is stopping this.”

Salih and other Kurdish Americans in the metro area — more than 2,000 — watched the news in disbelief last week after Trump turned his back on the Kurds by standing aside for Turkey’s “Operation Peace Spring” invasion of northern Syria, a Kurdish-controlled area holding thousands of ISIS prisoners behind bars.

During a press conference Trump tried to defend his decision by saying the U.S. has given weapons and “massive amounts of money” to the Kurds, but they didn’t help America fight at Normandy during World War II, which was a lie. Kurdish fighters could not join the Allies as a nation state, but thousands of soldiers fought alongside Great Britain and the Soviet Union’s Red Army. The Kurds also played a large role in overthrowing a Nazi-installed Arab nationalist leader in Iraq.

On Monday morning Trump further weakened his position by suggesting without proof that Kurdish forces were releasing ISIS prisoners to solicit American support, a statement that quickly received a backlash of criticism.

Kurdish Americans in the area are mixed politically, but many now say Turkey’s attacks can be attributed to one man: Donald Trump.

“It’s Trump,” Newzad Brifki, a former Moorhead teacher and the founder and director of the Kurdish Community of America in Moorhead, said. “I never doubted the guy, I knew he said some bad stuff, he made some bad decisions, but I was shocked. This is not the government of the United States, this was one man who chose money over people’s lives. He chose Trump Towers in Istanbul over the security of our country.”

In 2003, when the Iraqi war started, all eligible Kurdish men under 30 had to fight, Salih said.

“We had no idea what we were getting ourselves into, but we had no choice and we were the first ones out there,” Salih said. “My entire life I was always scared of being attacked.”

After fighting with the Peshmerga for two years, Salih fought alongside American troops during Operation Iraqi Freedom. During his time protecting soldiers, not one American died on Kurdish controlled soil, he said.

U.S. Army Major Peter Colt said that without Salih he and his men might never have made it home.

"His family kept us safe,” Colt said. “One could make a very fair argument my men and I are alive and safe because of his hard work and the work of his fellow Kurds.”

Trump’s betrayal of the Kurds is the generational equivalent of the United State’s betrayal of the Montagnards, or the Mnong people, during the Vietnam War, he said. More than 40,000 Montagnards fought alongside United States Special Forces, but were later forsaken when President Richard Nixon began ordering troops home. After North Vietnam’s victory Montagnards were slaughtered; survivors fled to Cambodia. The United States only took in about 2,000 Montagnards in the late 1970s.

“This is my generation’s similar moment,” Colt said. “Essentially we’ve walked back five years of effort strategically and militarily. It’s not good for anybody if we have thousands of ISIS detainees floating around in a country that is at war and awash with weapons.”

Colt, a retired Army major, recently published a detective novel entitled “The Off-Islander.” He isn’t a political strategist, but along with local Kurdish Americans, insisted a no-fly zone must be immediately enforced and harsh economic sanctions imposed. Americans from all walks of life must put political pressure on their congressmen and senators.

“Realistically, it’s a very slow process,” Colt said. “Ultimately, I think the Turks will achieve their strategic goals before that can become effective.”

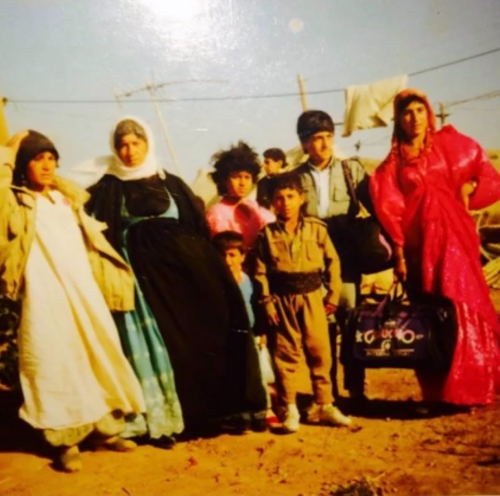

Jihan Brifki escaped Iraq with her brother and lived in a refugee camp in Turkey for years before emigrating to the United States, she said. Both she and her brother, Newzad Brifki, place no blame on the country that took them in, but point their accusations solely at Trump.

“We feel betrayed, back-stabbed, no matter how honest or loyal you are to your friends they end up betraying you,” Jihan said. “We had boots on the ground, we were your partners, we got rid of ISIS, we are just really upset.

“We were very shocked, even with Trump when he was running for President he was showing his support for the Kurdish people. Then all of the sudden he turns his back on the Kurdish people and is letting the Turks murder the Kurdish people. There is genocide going on right now. There are over 1,000 ISIS members who escaped a camp where Kurdish fighters were guarding it. Now there are videos out there showing ISIS members fighting together with Turkish soldiers.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes. It’s so bad. It’s so bad right now. They’re dying for no reason.”

Jihan has remained glued to her television news broadcasts since the invasion started, she said.

“I’ve been crying for days. How do you explain this to your kids? All these memories are coming back, from when I was four years old. I was one of the people who actually got poisoned, they poisoned our bread. The Turkish people poisoned our bread. Thousands and thousands of people got sick. I was admitted to the hospital because of that poison. There was another incident where they had barrels of water, we were all depending on water and there was no water coming in. There was a town about half an hour walking distance, but our camp was surrounded by Turkish military and they wouldn’t let anyone go out of the camp. We were begging and begging, and they refused, and they started shooting.

Another brother currently in Texas was shot in the thigh and the arm, she said. Friends snuck him out of camp into a hospital for treatment.

“I saw a man literally drop to the ground and he died right in front of my face,” Jihan said.

Memories of growing up in Iraq during the 1990s are filled with terror for Jihan.

“If you were a Kurd, or spoke Kurdish, you would be locked up in prison. If you named your child a Kurdish name, you would be locked up in prison. If you listened to Kurdish music, you would be locked up in prison.

“They’re scared that the Kurdish people will unite and create a country.”

Areas of Kurdish-controlled areas are now thriving cities, she said, filled with American restaurants, American flags, and with people who study English as a second language. Despite Kurdish support and love for America, the world remains quiet on the Kurdish plight, she said.

“That’s the biggest question: why? Why are they so silent,” Jihan wrote in a poem the day she saw children being killed in Syrian streets.

“Why is everyone turning their back on me? Why is the world so silent when I want to live so bad? Why am I so scared to die?… The world is watching me die, but nobody will come for me.”

Her husband, Jahwar Salih, now calls America, specifically Moorhead, his home, but will never forsake the idea of a Kurdish homeland.

“We have never picked a fight, they always come and destroy the Kurdish identity,” Salih said. “We want an independent Kurdistan, but we’ve struggled for years. We tried to do it in a peaceful way where we get the world to sign off on it, and then all of the sudden the Iraqi government would step in and it wouldn’t go through.

“But even if there’s one Kurd left in the world, they’re still going to want an independent Kurdistan. That dream is not going to get lost. I don’t understand why it hasn’t happened.”

Major Peter Colt said despite the Kurds being a democratic and accepting society, no country will give up land for the Kurds.

“The Kurds have been at war with other ethnic groups in the region for years,” Colt said. “Their big chance at having a nation came after World War I when they were promised a homeland by the western powers, then it became politically expedient for that not to happen. Why that hasn’t happened? In the 20th and 21st centuries we have nation states that didn’t exist before World War I and who are reluctant to give up geography and some of these areas are very oil rich. No nation is going to give up wealth or territory. It’s frustrating, especially since the Kurds have one of the best track records of civil rights. They’re the only ones who seem to be protecting other religions in the area.”

“We’re still asking ourselves that,” Newzad Brifki said. “Why aren’t the Kurds deserving people after they’ve given so much? Why is the world so silent? But this is a one-man decision. He screwed over our veterans and the American people, and he’s going to lose Christian and veteran votes because of this.”

“All we want is this war to stop,” Jahwar Salih said. “Stop killing innocent people, and for Donald Trump to back out of his conversation with Turkey to green-light their invasion of the Kurdish region.”

Far too few people in the Fargo/Moorhead area either know or seem concerned about the crisis in northern Syria, Jihan Brifki said. She once received a message on social media expressing concern, which brightened her day. Most of her posts on social media trying to alert friends and neighbors go unnoticed, she said.

“The Kurdish people are the most peaceful people in the world. “They’re all about democracy, they just want to be at peace and live free. Look at Kurdistan region of Iraq, it’s so safe and has developed so much, business-wise, and everything. Anyone who is human should stop this. I don’t care if it’s Donald Trump or a Republican. They’re all condemning this, how could you betray your allies?”

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)