News | August 29th, 2018

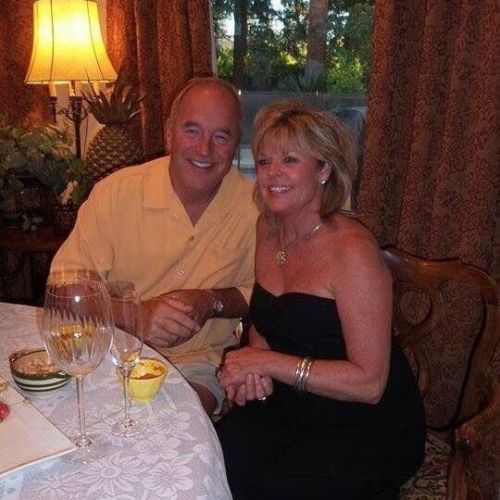

When Lloyd Ness’s cousin knocked on his front door, he didn’t need much sweet talk to sign an oil lease on family land. Lloyd Ness and his wife, Mary, read Samson Resources’ contractual fine print, received an attorney’s stamp, but put more stock in their good-natured cousin’s word as a trusted local farmer in Divide County. Slightly jaded from nodding donkeys and previous failed oil adventures, they didn’t expect much; wildcatters were a fickle bunch. But for a time, Lloyd and Mary Ness received an easy income, about two grand a month.

“Tulsa Two Step”

A year later, in 2012, the dream came toppling down in the Ambrose oil fields. Monthly royalty checks were shrinking. Ness’s cousin was fired from his liaison job when he confronted oil company Samson Resources on compliance issues.

Ness, a mechanical engineer by trade, didn’t understand why, so he began to dig. He discovered news about a consortium led by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, or KKR, a global investment firm, which included Japanese conglomerate Itochu, also Natural Gas Partners, and Crestview Partners, had bought Samson Resources for $7.2 billion, a deal that soon saddled KKR with $3.6 billion in debt and forced Itochu to sell back its 25 percent share for $1.

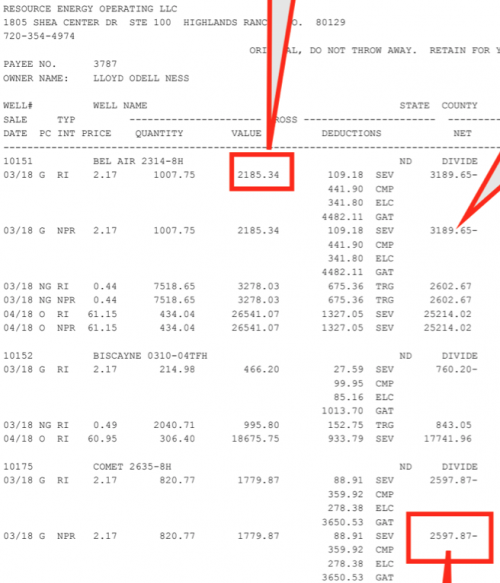

Company losses, he reckoned, had to be offsetted. Ness noticed a peculiar change in his checks: gas exploration fees were being deducted from his royalty payments.

He never signed up for that. Ness had agreed to one-sixth of the proceeds from wells dug on his land, but not to any hidden percentages. During one six-month period, Ness expected a check of approximately $30,000, but received a measly $1,600, with a 300-page-long check stub listing the same transactions multiple times.

“I call it the Tulsa Two Step, because they’re all from Oklahoma,” Ness said. “They get you to sign the lease, and then they bait and switch. They know they’re guilty, and it has become our job to hold their stinky feet to the fire.”

He filed an antitrust lawsuit in North Dakota in 2015 against oil extractors, because “the gathering fees were so huge, the overages were netting other royalty revenue.”

The gathering of crude oil is aggregating crude oil production, primarily through gathering pipeline systems which deliver crude oil to a combination of other pipelines, rail and truck.

Around the same time that natural gas prices plunged, Samson posted an operating loss of $2.1 billion, and filed for what became known as one of the largest U.S. energy bankruptcies ever a year later. KKR quickly divested $2 billion, and then Ness’s checks dropped even further.

Around the same time that natural gas prices plunged, Samson posted an operating loss of $2.1 billion, and filed for what became known as one of the largest U.S. energy bankruptcies ever a year later. KKR quickly divested $2 billion, and then Ness’s checks dropped even further.

Divestiture is the partial or full removal of an asset or investment from a business's books. Businesses can divest through sale, closure or bankruptcy.

Closure refers to the actions necessary when it is no longer possible for a business or other organization to continue to operate. Once the organization has paid any outstanding debts and completed any pending operations, closure may simply mean that the organization ceases to exist.

“After the price of oil started to drop, budgets became more in focus, and people started drilling down to where the devil is,” Ness said.

Ness’s pursuit of truth dragged him from where he lives now, in Arizona, to Delaware on five different occasions to object to Samson’s bankruptcy proceedings. The company, now known as Samson II, emerged from bankruptcy on March 1, 2017, according to its website.

The Tulsa Two-Step, a popular country shuffle on the dance floor, works as a slow con in the oil fields, Ness said. Oil operators withhold natural gas drilling costs from royalty owners, or deduct money directly from the wells. Many mineral rights owners can’t understand the convoluted small print or are obstructed when they seek answers.

“You do that times 12, or times 200 or 300 wells, and you got yourself a lot of money over the course of four or five years,” Ness said. “The overall money could amount to a billion dollars, more or less. Us royalty owners, we get our check details, we try to call the operators and they don’t answer their phones, and a week later we may get a letter.”

Ness is suing to change the scam, for in any other business those responsible would already be put behind bars, he said. He’s also seeking discovery in North Dakota federal courts to force disclosure of the ONEOK Rockies Gas Purchase Agreement. He claims that the contracts do not contain proprietary information, and are actually hiding agreements that detail torts, crimes, and the manner in which mineral rights owners and the state of North Dakota are being defrauded.

“It is a buy/sell agreement…effectuating transactions that are not with a third party vendor, and are not at arms length, and further conceals and suppresses relevant and substantive compounding acts, tortious acts, and embarrassing behavior and does not protect ‘trade secrets,’ but instead ‘protects the parties from the disclosure of criminal and tortious trade behavior’ that also contains mutually protective promises of silence, which are promises of secrecy and self-protectionism, mutually promising each other,” Ness wrote in the motion he is pursuing pro se.

Pro se means "for oneself" or "on one's own behalf.”

ONEOK is a natural gas liquids company based in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The company has invested nearly $5.3 billion in projects in North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Kansas, and is currently planning to build its fifth natural gas processing plant in the Williston Basin.

“That gas agreement exposes a lot of things. There’s not a royalty owner in North Dakota that is aware that 21 percent is given to the pipeline free of charge,” Ness said. “We’re only getting remitted for 79 percent. The gas agreement is fraught with torts and crimes that directly cause ‘overages’ that net oil revenues.”

In an email pertaining to the motion and directed at defendants, Samson Resources, Samson Investments, KKR, Magnum Hunter, Bakken Hunter, Williston Hunter, and ONEOK Partners, Ness stated that such practices of stealing from innocent people are disgusting, and that it’s too late for the companies to change their ways.

In other words, they’ve been caught.

“The gas gathering fee scheme that nets oil royalties…remains as a dynamic which is exploiting all leases, and still remains exploiting all innocent lessors, and has all along been employed since 2012,” Ness stated.

“It’s fraud. F-r-a-u-d.” Ness spelled the word. “And it’s corruption and there’s no other way to put lipstick on that pig.”

Lloyd Ness and his wife are just two people out of tens of thousands across American oil fields that are getting the short end of the oil stick.

A letter to the Office of the United States Trustee U.S. Department of Justice from Robins Kaplan, a California law firm involved in defending mineral owners’ rights, stated in 2016 that up to 75,000 landowners are being swindled by Samson alone across the country.

Fear, intimidation, and a secretive “contracts of silence” pertaining to settlement agreements, a bait and switch tactic of fee overages and skimming wells, keep most people silent.

A long-awaited audit resulted in the North Dakota Department of Trust Lands suing 10 oil operators including Continental Resources for improperly taking deductions from oil and gas royalty payments, a lawsuit that Ness helped initiate, he said. Continental Resources and the North Dakota Petroleum Council are disputing the claims, and oil operators are suing the state with the North Dakota Attorney General’s office defending the Land Board.

Bice vs. Petro-Hunt

Ness’s concerns aren’t the first time the issue of syphoning funds from royalty owners has arisen. In 2009, North Dakota Supreme Court Judge Daniel J. Crothers sided with Petro-Hunt over royalty owners’ concerns pertaining to a previous judgment allowing oil operators to deduct oil royalty fees to make natural gas marketable.

The practice is allowed, but ancient, Robert Skarphol, formerly of the North Dakota House of Representatives, said. His wife inherited leases signed in 1949 on the Beaver Lodge Unit south of Tioga, and they felt the sting of gas extraction deductions.

“What people find frustrating is that for a lot of years these practices did not take place, they’re authorized in most leases if you read the fine print,” Skarphol said.

“Like I said, 1949 is the first lease I looked at and the language is there, the language is authorizing them to do it, but natural gas was regulated until 1981, so there was no reason or purpose in doing it.

“Once the regulations came off there still was not an intent by the industry to utilize those provisions, and it wasn’t until the collapse of natural gas prices and oil collapsed later on that a very clever accountant figured out you couldn’t make money on the commodity, but could make money by charging administrative fees or new entities that we create that become middlemen in this process.”

The clever accountant, Aubrey McClendon, CEO of Chesapeake Energy and founder of American Energy Partners, LP, died in a high-speed car crash after slamming into a concrete bridge near Oklahoma City, one day after he was indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of conspiring to rig bids to purchase natural gas leases in Oklahoma. His death was ruled an accident.

“The money, the revenue, that is generated by these fees has become more attractive than the revenue or regular profit they can generate from the commodity,” Skarphol said. “Because hidden provisions are in these leases that surface owners that aren’t learned in the law, or are too trusting, were ultimately taken advantage of, and I find it disturbing that the courts stand for this practice when provisions are 70 years old and haven’t been used.

“I would think they were old enough they would have died somewhere along the line. North Dakota as a regulatory entity and as a legal system has taken a 180-degree different position than other states.”

In Texas, the courts are very protective of royalty owners, while in North Dakota just the opposite is true, Skarphol said.

“It’s because from the discovery of oil until 2007, North Dakota was begging for attention from the oil industry. We were willing to bend over backwards in the legislature to give incentives and so forth to get companies to come in and develop. The attitude was, ‘We want you, we’ll do anything to get you here, to keep you here, just tell us what it is you need and we’ll give it to you.’”

The richness of the Bakken oil is enough to entice any oil company seeking profits.

“Unfortunately that attitude has come back to haunt us, and is not serving us well,” Skarphol said. “In today’s environment, because of the attractiveness of the Bakken play, state government should no longer have that attitude. We are not indebted in any way to these people. Our legislature should very honestly give preference to the least learned in any court action… as is the practice in other mature oil producing areas.”

The real issue, Skarphol believes, is that the state has no agency defending the royalty owners. He plans to change that and is in the formative stages of creating a group called the Williston Basin Royalty Owners Association.

The association’s goal?

“To do what should have been done in the early 1950s, to become an entity that participates in the legislative process and ensure that legislators understand the needs of the people in North Dakota, who vote in North Dakota.

“The industry does a very good job of communicating to elected officials, who then hear one side of a story, and there is a vacuum with regard to when it comes to royalty owners. Since they don’t hear from them, they don’t think anything is wrong.”

The buck doesn’t stop there, however, but with the all-powerful Industrial Commission.

“It is becoming more and more concerning to have the entity charged with regulating the industry to be the one promoting the industry,” Skarphol said. “That needs to be given a good hard look by the legislature, unfortunately the legislature is not given adequate representation by the mineral royalty owners in the state of North Dakota.”

“Bice allowed reasonable deductions, the deductions that they’re taking is that they’re charging three times what the gas is worth,” Lloyd Ness said. “The affiliates are making far too much money.”

Another North Dakota Supreme Court case, West vs. Alpar Resources, Inc. filed in 1980, was a legal battle over whether oil operators should make royalty payments based on the gross proceeds without deductions. Supreme Court Chief Justice Ralph J. Erickstad reversed a previous McKenzie County District Court’s decision that sided with Alpar, further stating that all information in the lease must be disclosed, a favorable precedent for Ness’s motion for discovery.

Administrative exhaustion

Sarah Vogel once represented 240,000 farmers against the USDA from foreclosing on nearly 80,000 farm families during the 1980s farm crisis. She was the state’s first woman to become the North Dakota Commissioner of Agriculture, and also served on the Industrial Commission.

Vogel is a formidable force both in the courts and in the political arena, but lost three cases defending royalty owner rights and on flaring issues because the courts said she failed to exhaust administrative procedures.

“I’ve been a plaintiff in three of the cases, all of which have been dismissed for not on the merits but on failure to exhaust administrative remedies, which is pretty much an impossibility if you’ve ever looked at the administrative remedy offered by the Attorney General,” Vogel said. “It’s an impossibility because the expense is such that it isn’t worth anybody’s while to carry these cases one by one by one by one by one.”

For Vogel, who is also a mineral rights owner, said the costs of administrative avenues exceed the benefit, which is why cases are usually filed class action.

“You have to go through the hoops, and usually if there is an administrative remedy that you need to utilize, there is a remedy at the end of it, oddly enough in the case of the Industrial Commission administrative remedy, they don’t have the authority to compel payment at the end of the day, so what’s the point of the administrative remedy? Nevertheless, we lost.”

What offended Vogel most about the her Supreme Court case against Marathon Oil Company, was that Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem filed an amicus brief on behalf of Marathon in the North Dakota Supreme Court.

“In other words the State of North Dakota came down against the interests of mineral interest owners from the state of North Dakota,” Vogel said. “They came down on the side of Marathon, and I think that was an improper action, not illegal, but ordinarily an amicus brief would be filed on the side of citizens of North Dakotan,” Vogel said.

An amicus brief is a “friend of the court” brief by a party of a case that may or may not have been solicited to offer expertise or opinion.

“It was also adverse to the state of North Dakota, because the biggest mineral interest owner in the state is the state,” Vogel said.

At the same time, Stenehjem was receiving campaign contributions from Marathon, Vogel said.

Nine months after Vogel lost her case against Marathon Oil, Marathon gave Stenehjem two payments totaling $4,000, according to Open Secrets Center for Responsive Politics. During the same year Continental Resources gave Stenehjem $4,500, RJ Reynolds Tobacco gave $15,000, Exxon Mobil gave $3,000, MDU Resources Group gave $2,500, and ONEOK, Inc. gave $500.

“I think it creates an appearance of impropriety, if you’re a litigant in a court you don’t want the judge to be accepting campaign donations from the opposing party, and that’s what the Industrial Commission is doing,” Vogel said. “They’re accepting campaign donations from what is in essence litigants before them, while wearing the hat of the Industrial Commission. And they can say that didn’t affect their decision, but for someone like me, it looks bad.

“I don’t have confidence that I got a fair hearing. It makes people have less trust in the governance in the state of North Dakota.”

No flaring in the Bakken

Stand for a minute as the Bakken sun sets, and try to count the gas flare fires. Fingers on two hands aren’t enough. Flaring: the act of burning off gasses that build pressure and/or are too costly to trap, is also an illegal method to escape paying royalties.

Oil operators claim flaring is safer for the environment, releasing only carbon dioxide. Environmentalists and scientists say flaring also releases methane, a foul-smelling greenhouse gas that can cause extreme health issues.

Natural gas is an unwanted byproduct of oil extraction, but the gasses are a natural resource used for heating, cooking, and electricity generation.

Bakken wells are given a grace period of up to one year to flare, according to North Dakota law, and then are obliged to pay taxes and pay royalties on flared, or wasted gas. Failure to pay taxes on unmarketable flared gas is illegal, Sarah Vogel said.

“I was on the North Dakota Industrial Commission when we passed the rule that if an oil company flares after a certain cutoff point as sort of a built in sanction, they have to pay royalties, and they have to pay taxes, even if they burn it,” Sarah Vogel said.

According to October 2015 email records, Tim Knutson laughed at the flaring figures reported by the Industrial Commission on its website.

“I see the NDIC web site that Gadeco released it[s] gas figures for August,” Knutson wrote. “They have not flared any gas since May. Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Really? Ha ha ha Ha.”

David Tabor, the Production Auditing and Gas Measurement Supervisor, responded saying Knutson was “getting ahead of things.”

Bruce Hicks, the assistant director for the Industrial Commission, corrected Tabor, saying the numbers were due on October 5.

Six months later, Tabor replied, saying that the Gadeco well “will not be restricted as it is still within the first 90 producing days even though it is an older well.”

Gadeco, LLC, a Denver, Colorado company, is authorized for oil and gas exploration in the state, according to North Dakota Secretary of State records.

In 2017, Gadeco, LLC was able to reverse a district court’s decision in the state’s Supreme Court after Laurie A. Abell attempted to terminate an oil-drilling leasing contract.

Despite current law, Dakota Resource Council Executive Director Scott Skokos knows of wells that have been flaring constantly for 12 years.

“I don’t see a change in flaring at a visible level, and there’s no way to substantiate the volumes, without doing it yourself,” Skokos said. “You have to trust the North Dakota Industrial Commission, which is not a very trustworthy government agency because they’re tasked with doing both duties, regulating and promoting.”

The Dakota Resource Council is grassroots organization for responsible development of the state’s resources. They put citizen rights over corporate interests.

“Each field and each company is supposed to meet 10 percent flaring, over that percentage they’re going to have some of their wells throttled where they can’t produce as much oil,” Skokos said.

Figures released from the U.S. Energy Information Administration show that flaring rates have declined in North Dakota since 2014, but Skokos doesn’t agree. The flaring rights have remained the same because he believes the oil operators and the North Dakota Industrial Commission are in bed together.

Ending the Tulsa Two Step

Lloyd Ness is good with math. He can maneuver his way around a royalty statement. He’s waiting on a hearing date to compel discovery about the secret oil and gas agreement.

“What we are trying to do is get our government back to serving citizens,” Ness said. “Our only method of getting back at them is through a Class Action, and that is exactly what we are trying to do, is to get rid of the Tulsa Two Step.”

When asked if royalty payments have made him and his family millionaires, he laughed. Only a handful of landowners with thousands of acres have struck rich.

“We can’t let one apple speak for the whole bushel basket,” Ness said. “There’s literally tens of thousands of innocent royalty owners who don’t own ten thousand acres, they own 40 acres, or 160 acres, and there are brothers and sisters, like my family, and we share medium-sized acres, and we’re not millionaires.”

Some royalty owners have been charged gas fees that exceed their royalty payments, and end up owing the operator, he said. He plans to argue his case in court pro se, as he doesn’t want to be involved in a class action suit because court costs and attorneys eat up most of possible settlements. Operators involved in the Tulsa Two Step take the gas for free, but make it look like royalty owners are getting paid, while deducting fees from royalty paychecks. Instead, Ness thinks oil operators should just take the gas for free, plain and simple.

“That’s a heck of a lot better than charging us thousands of dollars and taking the gas for free,” Ness said.

Former Representative Kylie Oversen, who is currently running for the state’s Tax Commissioner’s office, said she tried to instigate a performance audit of the Oil and Gas Division during her time in the legislature, but was shot down.

“I would be extremely interested in seeing an audit of the companies that are extracting resources,” Oversen said. “The legality behind requiring that would likely come down to its relation to tax revenue. So, it is something I would strongly consider pushing for if elected Tax Commissioner. If there is a chance that North Dakotans are losing out on financial support that they are owed from the industry, we should know about it and take action to correct it.”

Ness, who is expecting to fight to the North Dakota Supreme Court, is also worried about a conflict of interest if the current North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem defends the state against Continental Resources’ CEO Harold Hamm’s lawsuit.

In the meantime, he’s waiting, watching, and ready for anything Big Oil throws at him, he said.

“It’s like having a side effect of PTSD, our antenna are up, we have eyes in the back of our head,” Ness said. “We’re not paranoid, but our house is protected. We know how to defend ourselves; we’re not scared. We are completely and utterly aware that we are up against some serious corruption, and this Tulsa Two Step has been going on for decades.

“This has been going on for too long.”

[Editor's note: previously mentioned Judge Zan Anderson was the trial judge in Bice vs. Petro-Hunt, Daniel J. Crothers was the Supreme Court Justice.]

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)