News | July 31st, 2019

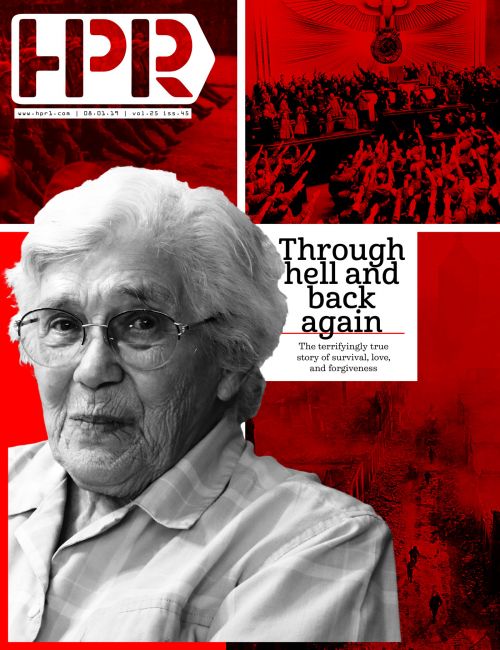

WALCOTT – When Gerda Jordheim was eight years old Adolf Hitler rode into town as the conquering hero in a military parade. She still remembers the Nazi salutes and hears the ‘Heil Hitlers’ her grandmother warned her against in her dreams. When she was 13, more than 69 Russian soldiers crazed by war raped her. Today, 80 years later, she is a survivor of brutal fascism, and fears for the country to which she immigrated.

“I just wonder why they want to do it now in this country?” Gerda said. “I cannot understand that, that’s why I don’t like to listen to the news so much when that is all they have on.

“What they do to the people now, like the other governments like Iraq and Iran and what they do to the people. And the camps here when they take children away from their parents in the camps, I don’t understand how that can be done. You know, when I went to school we were taught that the law was such a loving father [Hitler], and even then I thought when he is such a loving father how can he let that happen to the people in the concentration camps?”

Sitting in her sunroom with her husband, Arnold, far from her birthplace in West Prussia, the memories of what she went through as a child during World War II still bring tears to her eyes. Arnold, the “Norwegian husband” from North Dakota she caught along her journey, has been with her every step of the way since they met.

For decades the only person who knew Gerda’s full story was Arnold. She told it to him the first time they met in a gasthaus in Germany after the war. Arnold was stationed in a finance office at Leighton Barracks in Wurzburg; Gerda was working as a maid for an Army captain. She had just turned 20.

“I was reading a magazine, a sad story, and I had my purse here all the time too, and I was crying and somebody came and sat next to me and said, ‘Looky here little pistol-packing-Annie,’ and before I knew it was real I heard ‘bang, bang,’ and then there shot out the tear gas,” Gerda said.

“I had a few beers so I was feeling brave and I pulled the pistol out of the purse and pointed it to the floor and pulled the trigger two times and it was tear gas,” Arnold said.

The gasthouse, or guesthouse, emptied out quick, but Arnold and Gerda talked into the early morning hours. She talked of her horrifying journey and he of growing up in the North Dakotan plains. Together, they planted the seeds of a relationship that has lasted 61 years, and counting.

Outside in the Jordheim’s yard a German haus and a Norwegian stabbur sit under shady trees. Arnold built both as traditionally styled playhouses for their three children and later grandchildren. The family’s sunroom shivers with life. Clocks tick merrily along a wall. Surrounded by pictures and dolls, plants, blue willow pattern plates, and trinkets, laughter and jokes come easily for Gerda, which is nothing short of miraculous after hearing her life’s story.

1937 - 1939: When Gerda was a child

“We were free citizens until Hitler made us Germans,” Gerda said in her meticulous German accent. “At five minutes before five in the morning we heard a noise, and then a couple of seconds later we heard another thump, and the neighbors were looking out of the windows. Then we turned the radio on and they screamed ‘Heil Hitler, Heil Hitler, Heil Hitler.’”

It was the morning of September 1, 1939, and the seven-day Battle of Westerplatte had begun.

“That was crazy.”

After Poland surrendered the SS, or Nazi Germany’s secret police, came to Gerda’s apartment building ordering everyone out. Poles had dug tunnels under the town and were getting ready to detonate, they warned.

“Well, that was just empty threats,” Gerda said. “They stole everything we had. After a week we could come back, but it was emptied out.”

Born in a seaport near Danzig, now Gdańsk, Poland, in the free city of Neufahrwasser under the Polish surname Kaschubowski, “German purification” programs forced her mother to change the family name.

“Hitler made us change to a German name, and then it was Kalau,” Gerda said.

Gerda was born “out of wedlock,” she said. Her young mother, Herta, frequented the gasthauses along the waterfront and Gerda was the unwanted result of a relationship her mother had with a sailor, whom she never met until many years later.

Herta resented Gerda for the inconvenience, she said. When Gerda’s sister was born she took care of the infant while her mother worked sometimes as a streetcar conductor, other times as a newspaper delivery person, or at a local brewery, or the margarine factory.

Without a father, Leo Kaschubowski, her opa, became her father figure.

“He was the only one who was good to me,” Gerda said. “My grandmother never beat me, she never did anything wrong, but my grandfather always let me sit on his wooden leg, and he was the only one who was good. My mother would beat me until I could not sit on my behind anymore.”

Leo fought in the Kaiser’s army during World War I, lost his leg and was gassed in the trenches. His injuries drove him to take his own life when Gerda was six years old.

“He gassed himself,” Gerda said. “He came home one evening and my grandmother, I think they had a bad living, and my grandmother slept in the room with me. My grandfather knocked on the door and said ‘Come on out I want to talk to you.’ My grandmother said ‘You stay in bed, you are not going to go anywhere.’

“And then that morning, when my mother came home from a night out, he was hanging in the gas cooker. He had put the money in and so there was enough gas he had the hose tied to his neck and he was lying on the gas cooker.”

Gerda choked up at the memory, but didn’t wipe the tears from her eyes. She’s suffered on and off from post-traumatic stress disorder, she said, but talking about the past helps relieve the burden she’s carried for decades.

“They locked me in the room and I could not get out until they had taken him away.”

Two years after opa died, the first shots of World War II were fired less than half a mile from her family’s rented apartment.

“Just after that the Nazi armies moved into Poland,” Arnold Gerdheim said. “She then lived under the Nazis for six years.”

“And that was like hell,” Gerda said.

1939 - 1940: Hitler Youth

Like everyone else her age, Gerda was forced into the Hitler Youth.

“They were trying to make good Nazis out of them,” Arnold said.

“They tried to, but I got kicked out because I was considered an undesirable,” Gerda said. “That was hard, when you’re 8 years old and you see your friends marching down the streets singing and saying ‘Heil Hitler’ and they had a uniform on and I had to stand on the sidewalk, watching. It was very hard, but my grandma said it was the best thing that could have happened to me. She always said it would be a very bad deal to have him as a leader.”

Her grandmother hated Adolf Hitler with a passion, Gerda said.

“She said if you ever say anything about what I said about him, I’ll cut your tongue out, and that scared me,” Gerda said. “But we were trained not to say anything. That’s why I played dumb, and why I was kicked out of the Hitler Youth. I pretended like I could not understand. I just said that I had forgot.”

Her expulsion from the Hitler Youth made her the target of ridicule and bullying from other students.

“But I didn’t care,” Gerda said. “My grandmother was very good that way and told me to ignore it.”

With a total of only seven years of schooling, Gerda did most of her homework in lines waiting for food with government-issued ration tickets. Because her mother “was not very good to me,” and most neighbors understood Gerda’s predicament, the local butcher and the baker would set out a little white flag signaling to her if they had some special food available, she said.

Usually, her mother confiscated everything Gerda found. And if food wasn’t enough, she was beaten, she said.

Most people she knew weren’t true believers in Hitler.

“They faked it because they got better rations,” Gerda said.

Gerda was also a fingernail biter who during an inspection refused to cooperate with the Hitler Youth leader. She was slapped. Marianne, her younger sister, was beside her, and she bit the leader’s hand and Gerda pounced, which resulted in her expulsion from the Hitler Youth.

During the winter months grandmother Hedwig hid a short-wave radio under her mattress, and during the summer stashed it in the oven. When Hitler spoke everyone had to have the radio on, but she put plugs in her ears so she couldn’t hear the words. Gerda was forced into another room to stand in a corner so she couldn’t hear everything the Fuhrer said.

Nazi threats took on new meaning when soldiers punished a family in her apartment building. Everyone was forced into the family’s house to watch while soldiers nailed the tongues of a 2-year-old and a 3-year-old to a table and let them bleed to death.

Spies were everywhere. At school and at home she was frequently asked about her thoughts on the “beloved leader” or Hitler’s most recent speech, to which she remained mute, or always gave the same answer.

Trust was a trait she learned not to practice as perils also came from within the family, she said.

“My grandmother’s sister-in-law was the biggest Nazi in town,” Gerda said. “And we did not know that until she gave herself away. She kept asking all the time, ‘What do you think of our beloved leader?’ And I always had to say, ‘Oh, absolutely great.’ That’s what my grandmother told me to say.”

1940s: ‘Jew Lover’

“They kicked out all the teachers who wouldn’t swear allegiance to Hitler,” Arnold said. “And the teachers tried to indoctrinate them with all the Nazi ideas, and they told them that when they walked down the street and saw a Jew, they could spit on them.”

She and her family befriended Jews before the war, and did not intend to forsake the relationships because Hitler said so, she said. Gerda’s mother and grandmother were at one time labeled “Jew Lovers” because they were seen exiting a Jewish business.

During the initial phases of Nazi Germany’s extermination programs, more than 7,000 Jews lived in and near Danzig. Nazis told her family that they were being sent away to create their own country, but they were actually moved to ghettos, and then later to one of 1,200 concentration camps where more than six million died during World War II.

“We had Jewish neighbors, who were our friends,” Gerda said. “They had never done anything wrong. They were good people. And then when they took them away, my grandmother knew what was going on.”

Once during a visit to see relatives along the Vistula River, Gerda saw smoke coming out of a large chimney. She was told it was a factory, and didn’t know differently until after the war that the smoke she saw came from burning bodies at Stutthof, where soap was made from human fat and approximately 65,000 people were murdered.

“And when they saw us they had to walk in the gutter, all the Jewish people,” Gerda said. “And when they came and got them, and I had some friends who were Jewish, when they took them away they said they got their own country, they wanted to go to their own country. No, no, they took them to concentration camps. And after the war I had to clean them out, the bodies, in the ovens...”

1945: The Russians are coming

“You know, in all the years of war, we never lost a ship, we never lost a soldier, we were always victorious. Heil Hitler,” Gerda mocked.

She never believed the propaganda though, she said, especially after her cousin, Helmut, was drafted into the German Army at 15 years old. Another local 16 year old was accused of cowardice and hung in the Town Square with a sign around his neck reading: “I was too cowardly to fight.”

Gerda was a witness to the murder, one of many that were soon to come.

While German troops began to retreat en masse, she and other civilians were forced to shovel snow from the city streets. She saw a soldier with his intestines protruding from his belly begging her to slice his throat. As the Russian front neared in early 1945, she found herself in line with family trying to board the armed hospital ship MV Wilhelm Gustloff, which was later sunk by a torpedo, killing approximately 9,400 people and became known as the largest loss of life in a single ship sinking in history.

In March 1945, a Lutheran pastor Gerda remembers as Pastor Grossman of Neufahrwasser Lutheran Church moved up the date of Gerda’s confirmation, and the next day Russian soldiers sacked the city. Pastor Grossman was hung from the rafters of the church’s remains. Russians and Mongols swept through the city from the east and too fast for her mother to make good on her promise to gas themselves before they arrived.

“They came in at five o’clock in the morning just like the day when the first shot was fired,” Gerda said. “Our neighbors had built a bunker and we stayed there for many nights during the war. When the war came to an end that one morning there came these nails down the steps…”

She rapped her knuckles on the tabletop, hard and fast, mimicking the sound of cleats.

“They had nails at the bottom of their shoes. And then they opened up the door and said…”

Gerda rattled off a command in German meaning everyone to get out.

“Our neighbor lady who was nursing her baby, and they took the baby away from her and threw it up in the… My mother caught the baby. And then they grabbed me too. And then… ”

Her voice cracked. After a long and heavy pause, she continued.

“In three days and two nights I was raped by 69 Russians.”

“They did a bunch of gang raping,” Arnold said. “They put in an order saying you guys can raise hell for three days, you can loot and rape and do whatever you do.”

“It was one after the other,” Gerda said.

“That’s the way it was with the Russian army,” Arnold said.

“For three days, and on the third night it was forbidden.”

As a young girl barely 14 years old, the rapes didn’t stop on the third night.

“My mother made me go home to see if there was anything left in our apartment, and there came two drunk Russians in a Jeep,” Gerda said. “And they said to me, ‘Come here.’ And I would not go to them. Then they stopped the Jeep and the second one picked me up and put me in the backseat and he sat on top of me. And then they went to one shed and got me out there in the shed, and one was doing it.”

A second Jeep pulled into the area, Gerda said.

“And that filthy one who was doing it, he put his hand over my mouth telling me to shut my mouth. And I bit him. And I screamed. And that was the commandant of the town and he spoke perfect German. He came into the shed and shot his pistol and kicked him off. The one who was sitting in the corner to wait his turn, they took him along.”

Her would-be rapist was killed instantly, she said. The one waiting his turn was taken prisoner.

“The next day they hung him for all the soldiers to see that it was forbidden,” Gerda said.

The commandant asked him where she was going, and where her family was, but Gerda didn’t know. She was displaced, hungry, and destitute, with no papers.

Eventually, she was reunited with family, but Gerda was forced to pull bodies from the river with fishing nets, standing in dead, rotting bodies before rowing the flat bottom boat to shore where the rotting corpses were transferred to a “honey wagon” and driven to remote areas to dump as fertilizer, she said. Many bodies came from the MV Willhelm Gustloff, which was sunk months before.

“Can you imagine what we looked like? Standing in that all day long?”

“It’s estimated that upwards of two million German women and girls got raped by the Russian soldiers and about 10% of them committed suicide because they couldn’t handle it,” Arnold said.

“At one time when my cousin and I were in our apartment, and they came in and did that stuff, they poured vodka down my throat,” Gerda said. “I passed out. I came out of that drunken stupor first and when I wanted to open my eyes, I couldn’t open my eyes, I couldn’t open my mouth, it was all hard, caked. So I scraped my mouth, and I called for my cousin. They had manure all over the apartment, they put manure on the pictures of the relatives and everywhere. And they spread that on our faces.”

The manure was human excrement, Arnold wrote in a story about Gerda’s life that he finished in 2002.

1945 - 1957: Death

After the war ended Gerda’s situation worsened.

Two different times Gerda decided she couldn’t go on living, she said. Once, she lay across railroad tracks waiting the ten o’clock train that strangely did not arrive on time. On a second occasion a stranger pulled her back from the ledge of a bridge before she jumped.

Hunger was one of the worst enemies she had to face.

“We had no food then at all, so there were dead horses lying in the ditches and we did go and cut off some meat and eat it raw,” Gerda said. “We had nothing to cook with, you know. We also did go to the sea and pick up dead fish and ate that, and I don’t eat lutefisk anymore because, you know.

“When I came home without too much food my mother would beat me again.”

A witness to Germany’s ethnic cleansing pogroms, she then became the target of Russian ethnic cleansing of Germans for the communist-backed Poles.

“One day, they told us to go into the street for counting and we all knew it was not for counting,” Gerda said. “First they asked my grandmother if we wanted to become Polish citizens because we had a Polish name. She said no.”

Three days later her family was ordered out into the streets again.

“We were allowed to take our purse and they took that all away. The ration cards, birth certificates, all of it. And then they told us ‘march.’”

She was marched first to Danzig, then taken by overcrowded boxcars to Mittelbau Dora, near Berlin.

Mittelbau Dora was originally a sub camp of Buchenwald concentration camp during the war, supplying slave labor for Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun’s V-2 rockets and V-1 flying bombs. While Nazis ran the camp approximately one in three out of the 60,000 prisoners sent did not survive. The camp had the the highest death rate among the entire Nazi concentration camp system. Two years before the war ended the camp housed mostly political prisoners taken from Europe, and then in 1944 Jews were also sent to Mittelbau Dora where they underwent extreme cruelty.

During later Nuremberg Trials, only one SS guard from 19 at Mittelbau Dora was executed. Others were charged and convicted or were protected like von Braun in 1945 under Operation Paperclip, a secret recruitment program of the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency.

“They put us in cattle cars, there were more than 80 people in one cattle car and I had typhus already. I was pushed into the corner and there was the manure pile and I had to sit in it. But I was so glad I could sit all the time, I didn’t have to stand up. And in that cattle car I was the youngest one.”

The manure pile was the boxcar’s latrine.

The rest of the people inside the boxcar took turns sitting because there was no room, she said.

“Once in a while the Russian soldiers opened up the cattle car and pulled out the dead ones,” Gerda said. “Threw them out on the street.”

At 14, Gerda had already lost all her hair and her scalp was covered in scabs from lice. Before she was sent to the concentration camp she died, according to official paperwork. Doctors pronounced her dead, issuing a death warrant to her mother.

She woke up in a makeshift morgue after someone poured kerosene over her head. She heard screaming, but it wasn’t her voice.

“The doctor came in three times to take my pulse,” Gerda said. “The third time the doctor said I was really dead. All of the sudden I heard screaming, it wasn’t me screaming. I touched my head, that was not me screaming. There were all these bodies laying there and the nurse looked at me, I was sitting up and she kept screaming.”

Someone came up to her and asked what she was doing at the morgue.

“I don’t know. I showed them my name and he said, ‘Don’t you dare lie, she’s dead.’”

“I said that’s my name. And he said “Where’s your mother?’”

Her mother came to the hospital with her death certificate.

“She came and I was lying in that bed again and felt somebody was standing behind me. I opened my eyes and I looked at her… and I smiled.”

Her mother at long last had come to her rescue, she thought, but she was wrong.

“She said, ‘Why didn’t you stay dead?’ And then took the death certificate and tore it up and threw it at me.

“I was born with it, you see?”

Once healed of typhus, she was sent to Mittelbau Dora, and into another nightmare.

“We had to take the half-burned bodies out of the ovens,” Gerda said. “When we opened the doors, the bodies fell on top of us. We had to grab them and throw them on the cart. We could not lay them, we had to throw them.”

Those who could no longer work were dumped into water tanks where they drowned, she said.

She was released from Mittelbau Dora shortly after her 14th birthday. Her journey to the U.S. Army came years later after her new stepfather tried to rape her and her mother didn’t believe her side of the story, she said. She snuck aboard a train and fled.

1945 - 2019: ‘I’m going to make it’

Gerda forsook the church for 12 years after her time at Mittelbau-Dora. Scraping human remains from ovens, lowering bodies pierced through the necks off of meat hooks made her doubt the existence of any god. The years following World War II were hard on Gerda. She was released from the concentration camp and survived, working as a maid among other odd jobs, including chipping mortar from stones and bricks to rebuild her city, she said.

“So I worked as a maid since I was 14. But in the olden days I got paid for it. Now I do it for love.”

She winked, and looked over at Arnold.

Throughout her trials hope came with a handful of people who lent a helping hand. Her heroes or guardian angels during the post war years. They came in the most unlikely of faces, like the Russian soldier who physically kicked her backside to push her into West Germany, or the stranger who pulled her from a bridge’s ledge, or the woman who let her use a shower for the first time in months, or the train conductor who found her hiding on a gangway and found her a free seat on a train.

Arnold tried to convince Gerda to forgive her mother before she died, but Gerda is not sure she has. She’s not angry, frequently snaps out of her story to crack a joke. The nightmares don’t come as frequently as they once did.

“Gerda now holds no grudges against the perpetrators of the bad things that happened to her during the war, because she understands that everybody in Europe then was caught up in the winds of war and swept along with the tides of history in that tragic part of Europe,” Arnold wrote in his short story about his wife. “It was something that the common people, whether in Germany or Russia, could not do anything about. They were all simply caught up in evil dictatorships, either of Hitler’s or Stalin’s.”

A final hiccup occurred at Hector Airport in 1958. Because of time differences, Arnold was 30 minutes late and Gerda’s plane arrived 30 minutes early. They were married in Germany, but Arnold had to return home for work reasons.

“There she was all forlorn with nobody to meet her thinking it was all a wild goose chase,” Arnold said. Because she had no paperwork he solicited the help of state politicians for help, which expedited the immigration process.

“I didn’t jump up and hug him, I was just shaking so bad,” Gerda said.

Arnold’s Norwegian family had one important question about Gerda after she arrived.

“My grandpa came up and said to her, ‘Are you Lutheran, then?’” Arnold said. “He was afraid I had brought a Catholic back.”

She was a Lutheran.

“She really found a home here,” Arnold said.

“Then I got the mother-in-law who was the total opposite of my mother,” Gerda said. “When my mother was so mad and she said ‘Why didn’t you stay dead?’ I told myself ‘I’m going to make it, I’m going to show you.’ And I made it. Even so I had to take a Norwegian to boot, but I made it. Not in my wildest dreams did I think I would take a Norwegian to boot. Uffda.”

Gerda laughed.

Arnold found a job at the local post office. Gerda fell in love with America and began fulfilling her dream of raising a family. Together, Arnold and Gerda had three sons and so far, four grandchildren, one of whom was a linebacker for North Dakota State University Bison and won four championship rings.

Gerda’s mother died alone, estranged from family.

“It has been like a kind of therapy for Gerda to face up to all the things that had happened to her, and so finally, after many years, she has been able to shed the nightmares she had for many years and become accepting of the events in her life,” Arnold said.

“It worked out pretty good, I’d say,” Gerda said.

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)