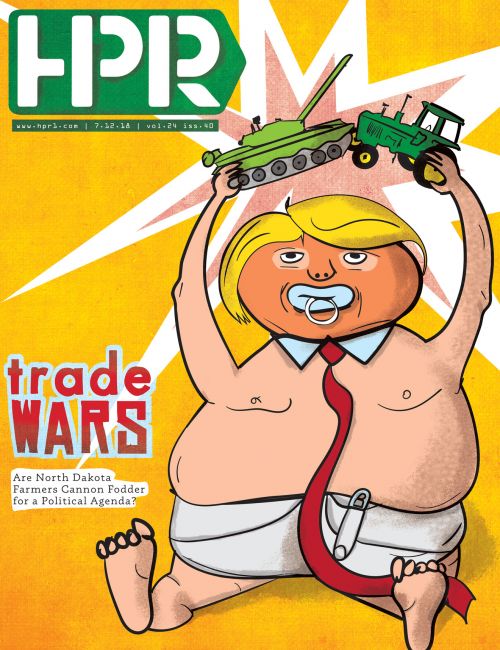

News | July 11th, 2018

NORTH DAKOTA – Jesse Stenson runs his family’s Centennial Farm, following in his great-grandfather’s footsteps. Originally, great-great-grandfather Johanes Stenson Hauge left Norway in 1855, and traveling by ox cart, squatted on land they were driven from by Dakota Sioux. For 21 years, Hauge tried his luck in America, facing severe weather, grasshoppers, and the hardships of the American frontier, but after losing his wife in a fire in 1891, he sailed back to the home country.

A year later, Haug’s son, Hans, returned, but only because his brother took his slot in Iowa’s 9th Infantry during the Civil War, and was killed at Shiloh. Hans Stenson purchased land near Lidgerwood, now population 1,296. Starting in 1900 with four sod houses, he farmed primarily grain and raised cattle, had eight children, and passed the homestead on to the second generation, then on to the third, and in 2012, to the fourth generation, Jesse and Matthew Stenson, according to Centennial Farm Application records.

Jesse Stenson broke the family tradition of planting grain, choosing the calculated risk of soybeans, used as feed for animals. Much of his product is typically sold to China. This year, before the trade war with China began, he planted 500 acres.

“This is where I grew up. It’s who I am,” Stenson said. “Even when I wasn’t home farming I was home farming. The world burns through a lot of soybeans, there’s a lot of demand.”

Earlier this spring, he locked in a portion of bean prices, he said, but not enough. Soybean prices were on the rise before the recent trade war with China, now they’re at a 10-year low selling at $8.55 per bushel. Soybeans like Stenson’s are used for the oilseed to make cooking oil and animal feed, and for the past decade have increasingly accounted for 60 percent of America’s $20 billion agricultural exports to China.

“Anything north of $9 is workable,” Stenson said. “I’m hoping it’s a short term political bluster, and I don’t see it having a lot of legs. The fundamentals are there. We’re burning through grain on a worldwide stage, if China isn’t going to buy our beans someone else will. But like I said, it has to be short term, if it holds on past January, guys have bills to pay.

“You got to pay the bills; you always have a banker to answer to.”

The United States Department of Agriculture estimates farmers planted 89.6 million acres of soybeans across the United States this year. Production levels are high, but prices are at a 10-year low. China uses approximately 11 million tons of food grade soybeans every year, and the number is expected to rise, according to the North Dakota Trade Council. China was expected to purchase about 1.14 million tons of American soybeans by August, but most if not all orders are likely to be cancelled, according to Bloomberg.

The initial skirmishes

In March, President Donald Trump’s Administration fired the first shots of a trade war with China, the main importer of American soybeans. Calling out the $375 billion trade deficit between the two countries, the United States first targeted steel and aluminum.

The first wave of tariffs hit $2.7 billion worth in Chinese steel and aluminum on March 1 by raising import taxes by 25 and six percent respectively. China responded a month later by issuing $2.4 billion tariffs on U.S. exports.

Trump’s administration retaliated two days later with its list of 1,300 Chinese products it planned to slap 25 percent tariffs on, totaling $46 billion.

On April 4, China hit back targeting Trump’s base support, making its own list of 106 American goods, including soybeans, cars, airplanes, wines, cotton, cereal crops, and more.

The next day, Trump considered adding $100 billion tariffs to Chinese imports, then banned exports to a Chinese telecom giant. After telecom company ZTE paid $1.19 billion in fines for exporting U.S. goods to North Korea and Iran, a violation of trade sanctions, Trump eased his stance, and a month later the seven-year ban on selling U.S. goods to ZTE was lifted.

On June 15, Trump announced another 25 percent tariff on $50 billion in Chinese goods, and China naturally responded with a revised list of $50 billion. Three days later, Trump threatened China with $200 billion more in tariffs if trade concessions could not be agreed upon.

China’s Trade Ministry responded by calling the proposal “blackmail,” and the Senate backtracked on Trump’s ZTE decision, reinstating the ban on the sale of U.S. components to ZTE.

Later in June, Trump asked Congress to review Chinese firms investing in U.S. technology, and then on Friday, July 6, at 12:01 a.m., Washington attacked, levying $34 billion on Chinese imports.

Beijing retaliated, marking what analysts described as a dark day for global trade.

China’s black list of American products include plastics, aircraft, propane, cereal crops, cotton, cars, chemicals, strawberries, wines, pears, apples, cherries, and soybeans. America is targeting China’s digital equipment imports, solar panels, flat screen televisions, and more.

China is, or was, America’s largest single-country trading partner, but the 28-nation European Union is Washington’s biggest trading political bloc with more than $1.1 trillion in goods and services in 2016.

“As the administration continues to escalate its ongoing game of chicken with China, North Dakota farmers and ranchers are increasingly worried about retaliatory tariff’s impact on major exports like soybeans, beef, and wheat,” Senator Heidi Heitkamp said in a press release. “A fellow North Dakotan recently said to me that patriotism doesn’t pay the bills – he’s right.”

Trade war tactics

Unpredictability of what President Trump or China, or the European Union, or Canada, or Mexico, or other countries will do next is one reason why commodity prices have fallen. One thing is for sure, Brazil, which is already the world’s largest soybean shipper, will step in and fill the gap left by retreating U.S. companies.

Economists believe the trade war may continue for years, and that real pressure won’t sink in until fourth quarter, when China usually turns its purchasing power to the United States.

If the trade war escalates even further, China could devalue its currency, thereby making Chinese goods cheaper and more attractive to international buyers, which would counteract the negative impact of American tariffs, according to the Wall Street Journal.

China could complicate “red tape” procedures on American companies manufacturing in China, such as blocking mergers involving US companies, delaying already convoluted licensing and renewal, or increasing inspections of American products, using a myriad of excuses to levy fines. China could also offer preferential treatment to non-American companies.

Reflecting previous and albeit failed Great Leap Forward campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s, China could also call on its farmers to expand soybean acreage and offer subsidies to help fill in the gap the trade war will create.

From the American side, soybeans could be sold to other countries, at least for the short term. Proponents of continuing the trade war say prices will adjust and vendors may change after an indeterminate period of turmoil. Promises that America will win a trade war are based on the idea that the country has no other choice: a service economy cannot sustain itself; a nation without a strong manufacturing base is vulnerable.

Historically, the United States imports more than $505 billion worth of goods from China, according to Market Watch. China imports $130 billion from the USA. The Chinese market is vital to North Dakota farmers, and it’s mentioned nearly 20 times in the June 2018 edition of The North Dakota Soybean Grower Magazine.

Despite the reputation that farmers voted for President Trump, not many are in favor of a trade war, which may hurt sales, putting the family or the farm at risk. The American Soybean Association sent a letter to the House Ways & Means Committee urging Congress to rethink tariffs on behalf of soybean growers.

“The letter urged Congress to develop a strategic plan to address problems with China and to ensure that U.S. families are not paying the price,” The North Dakota Soybean Grower Magazine reported. “The groups also pointed out that the administration’s approach does not adequately account for the role of the global supply chain in product production and assembly, which can take years to establish. The groups underscored that subsidies are not a long-term solution and that the loss of the Chinese market would be exponential.”

Last April, the Soybean Growers Alliance travelled to Beijing and Shanghai in an attempt to consolidate soybean growers’ voice to oppose market restrictions, excessive tariffs, and scientifically unsound barriers regarding the environment, health, chemical residue, and biotechnology approvals.

Simon Wilson, the executive director of the North Dakota Trade Office, an apolitical membership organization focused on helping state businesses, said two recent trade missions have been cancelled so far this year. The trade war, for him, started in February.

“In our opinion it’s started months ago,” Wilson said. “As soon as you start talking about it, the markets react. A lot of it has already been factored into the market.”

China has many tactics at their disposal, Wilson said, as they are safely sitting on stockpiles of soybeans and in no hurry to make concessions. Additionally, the prices of products like soybeans after tariffs this year in China aren’t much different than prices Chinese importers paid last year.

“At least for now, from what we see, China is comfortable as they have a very large stockpile of soybeans,” Wilson said. “They aren’t seeming to panic at this. They’re not rioting in the streets, they’re saying, ‘We’ll be fine, we’ll be fine.”

A strong U.S. dollar is also another factor that does not bode well for American farmers, he said. If China depreciates the country’s yuan, the dollar will only grow stronger.

America’s battle plan is much more limited.

“There are lot of different fronts,” Wilson said. “The strength of our dollar is also not helping our export business as well, our dollar is so strong compared to other currencies in the world.”

What will happen come harvest time is anyone’s guess as the strategies behind the trade war shift nearly daily. What is known is that – pending unforeseen climate events – this year’s soybean yield will be good, but where will farmers store their surplus?

“There’s going to be a lot of people wanting to sell, and there are a lot of beans left to be shipped, and a big crop coming, if this gets prolonged, where are they going to put their beans?” Wilson said. “Our beans will still be exported, maybe the last in the line, we may not have the best markets to sell into, especially if this is prolonged.”

Federal and state governments have made vague promises to remember the farmers.

“There has been nothing real other than saying we are going to help,” Wilson said. “There is a depression era program put in place then, but a lot of people we talk to are not sure how that is going to work. There is a lot of concern of ‘How are you going to make me whole?’”

In the meantime, he encourages farmers and businesses affected by the trade war to stay close to marketers, and stay close to the news.

Nationalism vs. globalization

North Dakota produces more than it consumes, and grows specialty crops such as high-protein beans and lentils. India was once one of the largest importers for such products, but in a protectionist ruling several years ago imposed tariffs and quotas heavily limited agricultural imports.

North Dakota farmers need to export their products. If agriculture exports are shutdown, jobs will be in jeopardy, the economy will drag, and consumer prices will skyrocket.

A rise in nationalism across the world is playing a factor in a larger world trade war, on many fronts.

“Like anything, there are ebbs and flows, and globalization over last several decades has really moved, and moved very quickly, and the flow of information allowed that to grow,” Wilson said. “The question is ‘What is going to happen? Do we even have a country? What is the definition of a country? Everyone wants to look out for their own constituents.

“A lot of times a free and fair trade is a utopia, it doesn’t exist. Nationalism is there, there seems to be more and more coming through.”

Level heads are needed at the discussion table, Wilson said, heads that will protect national interests, but also won’t impact the people needing protection.

“There are a lot of world trade disputes going on, but they take months or years to settle,” Wilson said.

Aluminum is one product America does not produce enough of, and imported most of its supply from Canada.

“To basically tax that when you couldn’t get it anyway, that cost will only be born by U.S. customers,” Wilson said. “Nationalism is there to protect, but I think you can go too far. When do you impact the people you are trying to protect?

“We don’t like arbitrary tariffs, and barriers to trade, we don’t think they’re good for anyone. History will show nobody wins in a trade war.”

Rising costs, plummeting profit

North Dakota is the ninth largest agricultural exporting state in the country, with 71 percent of the state’s soybeans shipped to China. In 2017, farmers planted 7.1 million acres of soybeans, which sold for $8.9 a bushel with a total production value of $2.13 billion, according to the USDA. Soybeans in 2017 were the state’s foremost agricultural moneymaker, topping wheat, corn, hay, beans, or sugar beets, by a wide percentage.

From social media threats to actual government policy, the trade war’s effects are already being felt in North Dakota, state Senator Jim Dotzenrod, the Democratic-NPL candidate for Agricultural Commissioner, said.

“Farmers need markets for their products, and they need a government that supports that goal,” Dotzenrod said. “North Dakota relies on export markets for agriculture and energy products as the driving force behind our state’s economy. However, with the Trump Administration’s policy of slapping tariffs on our trading partners, these buyers are looking for new avenues to fulfill their demand… This is a long-term damaging strategy for North Dakota farmers because we are telling our customers to find other suppliers.”

The trade war’s first punches may have been a duel between China and the USA, but Trump’s Administration is also targeting the European Union, Canada, and other allies.

“Starting a trade war with our closest allies is like playing with fire,” U.S. Senator Heidi Heitkamp said.

Heitkamp reached across the political aisle to help sponsor a Senate bill proposed by Senator Bob Corker, a Republican.

“It’s North Dakota manufacturers who stand to get burned,” Heitkamp said. “They’ve already seen their input costs spike because of the administration’s trade war with our closest trading partners like the EU, Canada, and Mexico. Now that the EU has predictably responded, our manufacturers could start to feel more pain as American-made equipment gets more expensive for foreign buyers and loses its competitive edge.

“This isn’t a good negotiating tactic – it’s giving up hard-earned market share for North Dakota companies.”

U.S. House candidate Mac Schneider showed support for the Republican legislation requiring congressional approval on tariffs.

“North Dakota farmers cannot operate profitably without access to export markets,” Schneider said during a press conference. “The threat posed by retaliatory tariffs on soybean producers and family farmer in North Dakota is real. Given the serious impact a trade war could have on production agriculture in North Dakota, it only makes sense for Congress to have a say on tariffs proposed by the administration based on national security grounds.”

Commodity prices are falling. Steel and aluminum prices are rising. Orders of soybeans are being cancelled and are being turned to other countries, such as Brazil, Argentina, Canada, or India. The North Dakota Trade Office reported a 15 to 20 percent increase on base prices for goods such as steel and aluminum.

The Farmer Business Network is predicting that American soybean farmers will most likely lose $40 an acre on this year’s harvest, a total loss of $3.5 billion.

“There’s no question that China has cheated its trade commitments with the United States, impacting American jobs and our economy,” Heitkamp said. “A better way of responding would be to look at trade enforcement to rein in China’s actions and create a level playing field for American farmers, ranchers, and manufacturers. North Dakotans know that solutions to trade imbalances happen at the negotiating table, not by playing chicken with foreign countries.”

The trade war is an issue that hits close to the pocket book for many North Dakota farmers, but so far, some elected politicians are doing little to step in, others, like U.S. Senator John Hoeven and Heitkamp, have at least talked to President Trump about improving the relationships. Current Congressman Kevin Cramer has said farmers don’t have “a very high pain threshold,” and has dismissed complaints of farming families worried about the future.

“As to the issue of China cheating and stealing and the trade deficit that’s been devastating to many of our American industries,” Cramer said in May 2018. “If we can keep politicians from hysteria we can help bring more moderate discussion to the table to calmly bring the markets back to an even keel. But that said, we have a lot of work to do, keep pressure on the administration… our administration, to make sure they have our farmers’ backs should there be any short term pain caused by a long term trade war. I prefer to avoid the trade war altogether.”

During President Trump’s “Make America Great Again Rally” in late June, Trump made reference to the trade war by saying America is winning.

“Thanks to Republican leadership, America is winning again,” Trump said. “And America is being respected again all over the world, we’re respected again. All over the world we’re respected again.

“We’ve gained seven trillion dollars in value. Trillion, with a T. Trillion. I have wealthy friends like Harold Hamm, they don’t even know what trillion represents. I say, ‘How many billions are in a trillion,’ and I’m not even sure Harold could answer that. But I will tell you what, we gained tremendous worth, economic worth, and other worth, more important worth: we’re respected again, we’re putting America first, we’re making great trade deals. Seven trillion. Now think of what that is.”

“And we’re going to get along with China, and we’re going to get along with the European Union, which has barriers from our farmers and our people selling product into the European Union. Last year with the European Union, and we love the European Union, we love the nations of the European Union, but the European Union, of course, was setup to take advantage of the United States, to attack our piggy bank, right? You know what, we can’t let that happen. Last year, with the European Union, we lost $151 billion dollars, we had a trade deficit of $151 billion. They send the Mercedes in, they send the BMWs in, they send their products in, we send our products in and they say ‘No thanks, we don’t want your product.’ And for all the free traders out there that’s not free trade, that’s stupid trade.”

For Jesse Stenson, North Dakota soybean farmer, everything from his farm to the world market is connected. He rotates his crops in order to keep his soil fertile. This year, soybean yields look promising, but with so much on the line it’s difficult not to pay attention to the political turmoil.

“Everything is connected; it’s not a soybean issue,” Stenson said. “We export everything we grow. Everything is a worldwide market whether you want to admit it or not.

“I’d hate to be a stock trader right now.”

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)__293px-wide.png)