Writer's Block | August 10th, 2017

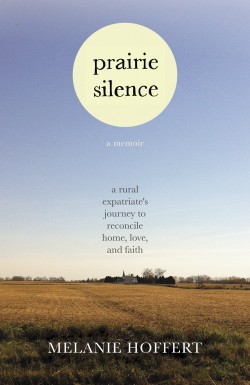

“Prairie Silence: A Memoir.” By Melanie Hoffert. Boston: Beacon Press, 2013. 238 pp. $24.95 cloth

From the outside looking in, North Dakota is an exotic locale, never more than when the topic of LGBT arises. It is a black hole of a state, a place from which no trans or gay could ever emerge.

For those of us who live here, the experience is quite variable. If one lives near a university -- and North Dakota is nothing if not a university state -- one may feel as though the subject is normalized. One can even find coursework, programs, workshops, and festivals on LGBT lives.

But away from colleges and large population centers, the LGBT discourse fades. That's why these two books, one on being gay and from rural North Dakota, the other on being a rural North Dakotan mother of a transgender child, are so important.

Both are authored by women. I'm not sure if this is why the prose they produce is so understated. Perhaps it's an expression of the culture here. North Dakotans tend to be plain-spoken people who don't draw attention to themselves.

It is a curiously fine characteristic, however, for the representation of LGBT matters, since, as mentioned above, outsiders would tend to exoticize.

Also, locals who don't know (or don't know that they know) any LGBT people may indulge in dramatic appraisals of us. They may traffic in stereotypes of people who are highly sexualized and predatory, or of people who are impossibly strange, abject, and lonely.

Nothing could be more normalizing of the LGBT in North Dakota than Hoffert's memoir. In this case, the author is the gay person in question. Her depiction of herself is sympathetic and relatable.

Yes, she did "escape" to an urban area, but acceptably so: she went to the Twin Cities, not terribly far from her family of origin. This allows her to return home regularly, as she does with pleasure, although with increasing discomfort as her city life as a gay person goes unrecognized back "home."

The story revolves around her initial inability to trust her North Dakotan family and neighbors with the news of her sexual orientation, but it is also deeply imbedded in the Upper Midwest rural culture.

Forced to speak to strangers seated beside her on an airplane, she makes a ruefully comic observation about her identity. She never frets about revealing her homosexuality, she says. "The eyebrow-raiser is this: I'm originally from North Dakota."

Of course, the irony is that the ideal reader of this book is more like the airplane passenger that is not from North Dakota. We read the book to discover whether and how she will be accepted by family and friends -- from North Dakota! -- when they finally discover a central fact of her existence.

Most of the book is a wind-up to those conversations in the latter portions of the book in which she comes out to them. But by the time she broaches this subject, we have come to know her family and the closeness that defines their relation. It would truly be tragic if they didn't come around. Spoiler alert: they do. Every one of them accepts her and her partner.

It seems possible that in rural areas of the United States, homosexuality can be "othered" in the abstract, yet obviated in the specificity of a life one already knows and values.

In such instances of acceptance, the phenomenon that Melanie Hoffert calls "prairie silence" must be breached. The phrase draws on the dark discourse of the closet.

But there is another meaning of "prairie silence" that is more equivocal. True, it's not that easy for anyone in North Dakota to have any kind of interior or social "problem." It's simply the case that no one wants to hear such things. "Can't you get over it?" is the usual reply to these confessions.

In my view, this is a cultural failing, especially considering that the antidote to bad feelings is generally heavy alcohol consumption.

Yet in this book, "prairie silence" isn't only a negative. The vast, open landscape itself seems to require it, as though private contemplation were the proper response to such a natural wonder. And what need for "communication" when we share this?

For farming families, what is shared is also a working interaction with that land. Families and neighbors (at least in the past) depended upon one another in myriad ways. This dependence upon the land and upon one another is apparently not so easily broken by spurious "outside" intrusions, such as modern identity markers like "gay" or "trans.”

Even though the plot has been spoiled, Hoffert's book has much to recommend it, including a sometimes inventive and witty style.

"Wait, wait. What? I shook my head like a cartoon character flattened by falling off of a cliff, who now needed to inflate my body, starting with my head."

Her insights into the people she has grown up with are keen; she paints readily recognizable characters. Brought to life through her prose, their ordinary lives are ennobled.

That she has left and returned is key to her insights. The adult memoirist can see her loved ones through ironic eyes, eyes that just as easily turn back on her own new worldview. She watches her father plan for months the destruction of an old barn that carries for her a citified nostalgia. "Pottery Barn would kill for the wood," she laments. "They can come and get it then," is her dad's gruff reply.

“Out of the Blue: A Mother's Memoir of Our Family's Transgender Experience.” By RoxAnne Moore. New York: Page Publishing, 2017. $12.95 paper; $9.99 e-book

Although there are no farmers in RoxAnne Moore's story, family is again the touchstone of meaning. This nonfiction account of a decades-long process of change centers intensely on the consciousness of the mother of the adult child, who leaves home as a heterosexual daughter, then becomes a homosexual daughter, and finally, a heterosexual son.

Like Hoffert's first-person narrator, this "I" has access to discourses that originate not just in small-town enclaves but also in cosmopolitan ones.

Moore's book is a revision of a master’s thesis, and “Out of the Blue” begins in consultation with other writers and memoirists who recount their knowledge of, or experiences as, transgender people.

It's certainly interesting to follow the author-narrator through each of the transformations of her child. That remains true even though we know from the outset that it is the trans identity that has provoked the memoir.

Should some obstreperous wag joke that homosexuality is the gateway drug to the transgender, this book will have no rejoinder. It is sober and sensitive, and not a little poignant.

This is so because the changes that the child experiences directly reach the mother primarily as a series of reports that must be laboriously and hermeneutically unpacked. What's truly absorbing is to see it happen through a mother's consciousness. She knows from the outset the so-called "politically-correct" perspective (my phrase, not hers).

But merely adopting the proper face and terminology is hardly the point for her. She is this child's mother. She is concerned for her child's welfare. The situation is not that of accepting a clear and present empirical reality (never mind the social ramifications). It is more a matter of disentangling a knotty amalgam of discourses within which both she and her child are struggling.

Through it all, she must determine what is her role as a mother in all of this. How can she best support (and sometimes, protect) this child that she has always treasured? Parents are supposed to know more than their children about what it means to become mature adults. Is that still true in a case like this?

Moore decides that the best strategy is to remain as open as possible to the communications and gendered performances of Tommie, previously known as Cathy. That this might be extremely difficult to do should be obvious. There is nothing that is more of a given than sex/gender. Indeed, one of the early chapters in the book is "Is It a Boy or a Girl?"

Throughout most of human history, one's primary social position, as well as one's place in the reigning cosmology, was achieved through the simple (as it was then seen) verification of maleness or femaleness. Onto that definitive physical divide was pinned every hope, every expectation of a natural unfolding into one's complete humanity. There are few discourses that can rival the power of gender.

While the well-educated mother-narrator of this book might be thought to occupy a somewhat different social space from those of her neighbors, she seems to have maintained a strong sense of belonging with family and friends. Such comity is one of potential losses facing both the child and family of the gay and the trans.

One of my favorite passages is when the writer punctures one of the platitudes that usually pass blissfully from one parent to another. "'All we want is for our children to grow up and be happy.' I want to say to them, 'You just wait until your child grows up and doesn't follow the path YOU think is best for them!'

But I don't say it. I'm not sure why, but I don't. Maybe it's because I'm aware that unless you actually live the experience that teaches you that kind of lesson, it'd just go in one ear and out the other."

The grumbling tone and the ending of the passage with another adage achieve a certain perfection of expression. Life lessons are, after all, the form that human wisdom often takes in rural areas. But there's a limit to their explanatory utility--as well as a limit to our author's patience.

Ruptures to traditional discourses on gender and sexuality appear as a threat to the social structure. The mother of this story has books and PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) and a loving husband to accompany her through the shocks and strains, but nevertheless she suffers. What role does a mother have once her children have grown? The role of grandmother.

"Bisexual, she had said. The word still bothered me but she'd reassured me she still loved Bob. My hopes of becoming a grandmother might be delayed but weren't dashed completely."

The gradualism of the changes do seem a kindness. But every new revelation from her child is a fresh wound that can't be shared with those who used to offer friendly assurances. Moore recounts times when neighbors are bragging about their children, noting glumly how she cannot enter the competition.

Both of these books are quite readable and informative for those who need to learn more. They will provide worthy companionship to those who have suffered similar fates. As representations of North Dakota and LGBT lives, they stand as achievements for us all to be proud of.

Every library in the region -- and beyond -- absolutely should order them.

April 18th 2024

October 2nd 2023

April 23rd 2023

March 15th 2023

March 8th 2023