Writer's Block | March 6th, 2019

BISMARCK – Shadows are the true reflections of Shane Balkowitsch’s wet plate portraits. Whether he’s photographing Sitting Bull’s oldest descendant or documenting Indigenous modern struggles, he’s also exposing – one glass plate at a time – the darker underbelly that believed not too long ago Natives would no longer exist by 2019.

His work capturing Native portraits with the wet plate photographic process earned him the Hidatsa name Shadow Catcher, or Maa’ishda Tehixixi Agu’agshi, given to him during a naming ceremony by Three Affiliated Tribes historian Calvin Grinnell “Running Elk” in October 2018.

Testament that Native communities across North Dakota and the country have defied European-American colonialism and have retained their culture, their traditional dress, and their dignity to modern times, Balkowitsch’s 289 portraits have already been on display across America – from Moorhead’s Rourke Art Gallery to the State Historical Society of North Dakota to the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum – and have been safely stored within the North Dakota State Archives.

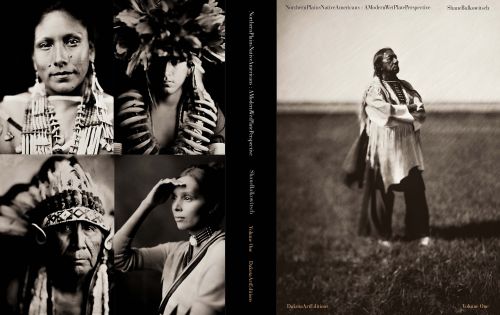

Now, his first photographic book, “Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective (Volume I),” featuring 50 portraits beginning with his first shot of Ernie LaPointe, the great grandson of Lakota Chief Sitting Bull, will be published and available at a book signing on June 23 at the North Dakota Heritage Center.

“The great-grandson of Sitting Bull came into my studio and changed my life,” Balkowitsch said. His photograph of LaPointe is named “Eternal Field.”

“Like Edward Curtis who took pictures of Native Americans in the 1900s, he would have thought that they would be a lost race, that they would be long gone by now,” Balkowitsch said.

Edward Curtis was a dry plate photographer who struggled a lifetime to document Native culture in the early 20th century, a man that Balkowitsch studied and admires.

“The funny thing is that now when I post these pictures, people ask where are they getting the costumes,” Balkowitsch said. “There are no costumes; this is their regalia that they own. This isn’t a game. This isn’t that they’re pretending to be Native Americans in my studio. This is their formal dress. People think I got spears and bows, no, I don’t have a bow, you bring a bow and I will take a picture of you with your bow.”

Balkowitsch comes from German ancestry, and said there are few things other than his love of sauerkraut that defines him as German.

“The Native people still have their regalia, their culture is still alive. They’re still coping like we all are and dealing with modern day stuff. It has not been driven from them.”

Native names taken by professional sports teams, or those who play at dress up with a headdress for Halloween are signs of envy, Balkowitsch said.

“We find it interesting so we steal it,” Balkowitsch said. “We idolize their heritage but then we also oppress them. We take what we want, and cultural appropriation is not a good thing, it’s a bad thing because they don’t appreciate it.

“You don’t ask the rapist his opinion… you don’t ask the guy who pillages, you must ask the victim what their opinion is and how they feel.”

Native regalia isn’t a requirement for a portrait, some come in blue jeans and baseball caps.

“That’s why it is called a modern wet plate perspective, because it’s important to capture modern clothes as well,” Balkowitsch said.

“To the world I would like them to know my Native American friends, brothers and sisters, that they are still here, they are not gone, they may be two percent of the population, but I would think that Edward Curtis would look down on us and smile.”

A Bismarck resident, Balkowitsch knew nothing of the photographic process when he began. He discovered a wet plate photograph of a motorcycle in 2012, and despite professionals telling him he would never succeed, began studying, hundreds of hours of research. His first wet plate came out successfully: it was a picture of his brother, and he’s taken one of him every anniversary since.

His interest in documenting Native culture came in 2014 when the LaPointe walked into his studio, located at the time in the warehouse of his own business, Balkowitsch Enterprises, a medical equipment distribution company.

He brought his camera, wet plates, and bulky tripod out to the frontlines of the Dakota Access Pipeline before private security company TigerSwan rewrote the narrative, a time when local police and protestors were still smiling, he said.

For Balkowitsch, there are details in the shadows that photographers, especially wet plate artists, must catch. A long exposure and the image burned onto wet plate glass will be bleached; too little light and the photograph will be useless.

Once calibrated and focused, the subject must sit still – without blinking – for ten seconds. Anything less and the image will blur. The wet plate collodion process began 168 years ago, shortly after the daguerreotype process.

For years, Balkowitsch has poured his own time and money into his study of the wet plate process, capturing images on his own dime. Each plate requires chemicals such as silver nitrate solutions, which don’t come cheaply.

Since his journey began, Native communities have flocked to his studio to have their portraits taken. Margaret Landin YellowBird, who is with the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara Education Department, frequently helps him. She ensures people are comfortable, acts as a liaison between him and the tribes.

Now, he has a waiting list – and not only Native Americans – that is seven months long.

Balkowitsch doesn’t make money from his Native American portraits, and always gives them a free print and digital copies. He’s moved from his warehouse after building the state’s only natural light environment studio. The studio is also open to aspiring artists upon appointment.

His book will be available in June, and is ready to preorder now. Each hardback copy will be a limited edition, signed, numbered, and will contain a sleeve in the cover with a historically styled, rounded-edged cabinet card picture. All book sales will benefit the American Indian College Fund.

Murray Lemley, born in Hope, North Dakota, but now living in The Netherlands, will be publishing Balkowitsch’s book. He discovered Balkowitsch after he published a book on Frank Bennett Fisks and portraits of Standing Rock from 1900 to 1920.

“I think Shane’s work is brilliant and this is one very good way to get more people to see it,” Lemley said. “He has a loyal following already on social media who will love this book and with proper distribution we will expose the work to a much wider audience.”

Balkowitsch’s work is unique because he combines a historic process with modern sensibility, Lemley said.

“He has a very good photographer’s eye and a compassionate way of working with those whom he photographs. He has developed a collaboration with his sitters that is truly inspiring. They trust each other; they work together.”

During the 1970s, Lemley, also a photographer who has his own publishing company called Dakota Art Editions in Amsterdam, studied at North Dakota State University and was involved in photography projects with Turtle Mountain for the Smithsonian.

One of Lemley’s next projects he hopes to finish is the “People of Hope” book that will feature 100 people from his hometown during its 1982 Centennial.

Balkowitsch plans on photographing 1,000 Native portraits over the next 20 years and publishing a series of four books, each one focusing on his favorite photographs from the series. All the plates he creates for the project will be gifted to the Historical Society’s permanent archive.

“If fate does not break my stride, I will do everything that I can to see this through,” Balkowitsch said on his website.

February 18th 2026

December 18th 2025

June 19th 2025

June 19th 2025

June 19th 2025

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)