Live and Learn | June 10th, 2015

By Lisa Nawrot

By Lisa Nawrot

Tell me if you’ve heard this one: Benjamin Franklin, Antoine Lavoisier, and the inventor of the guillotine walk into a room together … no, this is not a joke (the Dalai Lama says to a hot dog vendor “Make me one with everything,” That’s a joke). This meeting took place in Paris, 1784 where a Royal Commission was tasked with debunking a new pseudoscientific practice named for its inventor, Franz Anton Mesmer. Mesmer claimed to use magnetic forces to induce a trance-like state and treat a variety of ailments. A century later, Jean-Martin Charcot speculated that hypnotism might help treat hysteria. Charcot was an accomplished neurologist and the first to describe Parkinson’s Disease and ALS (originally named for Charcot but now known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease). It was Charcot’s student Sigmund Freud who went on to develop ideas about the power of the mind- especially the unconscious mind- to affect the body and brought about a revolution in the science of psychiatric medicine.

If you’re like me, you love this sort of academic bric-a-brac. It’s fun to uncover something unexpected inside the familiar wrappings of history and science, sort of like bridge mix for your brain, a big salty bowl of mental mixed nuts. Did you know that another follower of Mesmerism was Stanley Milgram, who infamously demonstrated obedience to authority using a fake electric shock scenario. But did you also know that he studied the size of social networks by tracking people's connections across the U.S.? Milgram’s “small world” phenomenon was an early form of the six degrees of separation idea, though he never used that term (and presumably hadn’t seen any Kevin Bacon movies).

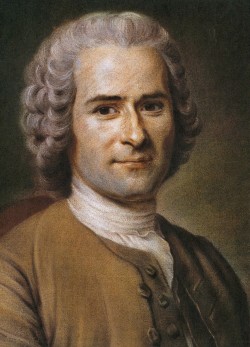

Maybe it’s a midlife thing, but learning is like leftover Thanksgiving dinner: It’s much better the second time around. I like playing this sort of cerebral hopscotch that connects people, places and ideas in ways that the typical textbook never imagined. For example, did you know that French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau, who wrote “The Social Contract,” was also a composer of classical music (one of his operas was later arranged by Beethoven)? Rousseau is famous in the field of developmental psychology for his ideas about the innate goodness of the human infant, and his groundbreaking book on education “Emile” proposing a unique child-centered approach. Interestingly, Rousseau sent all five of his children to a foundling hospital shortly after birth.

Lillian Gilbreth had 12 children, which didn’t stop her from earning the first Ph.D in Industrial Psychology in 1915. A pioneer in her field, Gilbreth authored a classic textbook “The Psychology of Management” and consulted with a variety of businesses including Sears, Macys, and Johnson and Johnson. Her story was the inspiration for the movie “Cheaper by the Dozen”. Rewind a hundred years to another pioneering woman Ada Lovelace, an English mathematician who worked with Charles Babbage on the difference engine, an early forerunner of the modern computer. Perhaps it was the influence of her father the poet Lord Byron that prompted Ada to question the creative potential of intelligent machines and conclude that a machine can only do what it is programmed to do. This skepticism towards the potential of artificial intelligence came to be known as the Lovelace Objection.

There is even an incredible fictional woman featured in the history of science. “Wonder Woman” was the creation of William Marston, whose mentor Hugo Munsterberg created forensic psychology. Munsterberg’s 1908 collection of articles “On the Witness Stand” explored the shortcomings of eyewitness testimony including the psychological factors involved in detecting lies and forcing confessions. Marston’s doctoral research on blood pressure and deception was instrumental in the invention of the polygraph. Lasso of Truth anyone?

My favorite scholarly scavenger hunts turn up interesting personal anecdotes that help to humanize the scientists I have come to revere. For example, Naturalist Charles Darwin, whose voyage aboard the Beagle inspired “The Origin of the Species” did more than just collect and catalog the creatures he studied. At Cambridge, Darwin was a member of the Gourmet Club where the featured menu was decidedly exotic fare (talk about tasting the fruits of your labors). The father of experimental psychology Gustav Fechner quantified the relationship between physical energy and perceptual experience creating the science of psychophysics. But under the pseudonym Dr. Mises, Fechner indulged his more humorous side with publications including “On the comparative anatomy of angels” and “Proof that the moon is made of iodine.” And even the image of the great philosopher Descartes can stand to lighten up a bit. Descartes’ self-evident argument for existence “I think therefore I am” led him to believe that the mind was separate from the body. Apparently the universe has a sense of humor because after his death Descartes was decapitated and it was more than three hundred years before his body parts were reunited in a single grave.

Now it’s your turn, so send me your science story: Funny or serious, stupid or scholarly, humorous or heinous. No promises to connect it back to Kevin Bacon though. Email me at enawrot@cableone.net.

January 15th 2026

April 3rd 2025

March 15th 2025

March 15th 2025

December 19th 2024

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)