News | September 14th, 2016

By C. S. Hagen

cshagen@gmail.com

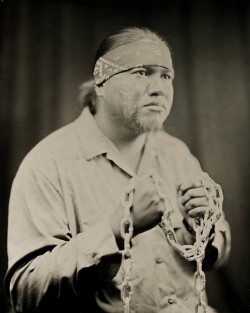

Americanhorse, known by friends as Happi, doesn’t see himself as the local hero he has become in online headlines and print media. He’s well spoken, peaceful in presence, commanding a quiet authority with his six-foot tall, 250-pound frame. Like many his age, he doesn’t know his native language, but intends to learn.

On August 31, the 26-year-old Sicangu-Oglala Lakota warrior pushed aside his fears, and leapt onto an excavator, forcing the driver to shut down the engine -- in accordance with OSHA regulations. Fortunately for Americanhorse, the driver walked away, saying he got paid whether he worked or not. Wrapping his arms around a part of the machinery, he chained himself with a plastic pipe smothered in tar. For six hours, law enforcement tried hacksaws, crane lifts, pondered how to disassemble the machinery before he was freed.

And then he was arrested.

Most netizens applauded his bravery. A few made comments to cut off his arms, or use a bone saw.

To Americanhorse, the pending court date is a small price to pay to protect water and land. “My main focus is this fight, and it’s all over the continent, in fact it’s all over the world,” he said. “When we’re done with this fight, and we’re going to win this fight, I am going to go look for allies that came here who have their own problems and I want to be able to sit there with them and fight those fights, whatever it is they’re fighting just in solidarity for them doing the same with me.”

Not in seven generations have Native Americans come together in such strength, he said. Old grudges have been cast aside. Daily, tribal leaders stretching from one coast of North America to the other stand to speak before the hundreds, sometimes thousands gathered. One of the most historical moments was when the Crow tribe, one of the Sioux’s oldest enemies, arrived at camp in a show of support.

Historically, the US government has tried to eradicate Native American culture, Carina Miller, a councilwoman from the Warm Springs Tribe in Oregon, said. She heeded the call to rise at 5 a.m.

“Get up. They’re back,” someone in the darkness called out. “Get up. They’re back.”

She jumped into her “pony," a 2010 Chevy Cobalt, with friends and drove to the site, but company workers could not proceed; the ground was too wet.

Miller grew up on a reservation, the local school district did not allow her to learn her own language, and she feels the government tried to erase her and her tribe.

“They pit us against each other, breaking treaties, trying to wipe us out,” Miller said. “People need to understand history.” Today, her tribe fights Nestle over water bottling rights on Native American land in Oregon, she said. The gathering of so many indigenous nations has brought her hope for her homeland.

“It’s a really strong and powerful presence,” Americanhorse said. “It feels like it is going to be a lot easier for us to work together. If we can establish a way we can work together here, then in the future when another issue comes up, something threatening another indigenous tribe, we can get together.”

The road to becoming involved in the fight to protect water and sacred lands wasn’t easy, but in the end, the decision to give up his old life was. All roads pointed to the Camp of the Sacred Rock. As a child in the public school system in Colorado, Americanhorse was shunned both by white people and other indigenous tribes, like the Utes and the Navajo, he said. He learned to shy away from outsider help, grew up with violence and chaos. Drank on the weekends.

In town, he has to constantly stay on the lookout for out-of-town pickup trucks. Where there are work trucks, man camps cannot be far away in western North Dakota. Where there are mancamps, there are the cartels. And where there are cartels, sex trafficking, methamphetamine dealers, not to mention frustrated men with too much money, are in abundance.

“They prey on the indigenous women,” he said. “It’s not talked about, because

they’re up here in North Dakota where everyone is supposed to be making all this money, but nobody really cares.”

He said indigenous towns such as Cannon Ball, have monstrous problems with teenage suicide, methamphetamine use, and a desperation that can be known only to the downtrodden.

“It’s weird when it comes to race,” he said. “The race issue for me was a pretty big thing. I thought all white people were racists.”

Americanhorse’s mother was the one who offered a helping hand, slyly roping him into fighting pipelines, he said. She introduced him to horses, and then to the KXL pipeline fight.

“At first I didn’t want to be there, I didn’t want to help. But that was the first step, going to the pipeline and to that fight was my first step in the right direction.”

But after the KXL pipeline project was defeated, he returned home. Went back

to his normal jobs, sometimes as an assistant manager at Dominoes, at other times a casino in Colorado.

“I was walking in a world and a reality where I was worried about a certain image of me. I didn’t really think of where things came from or how they were made, and I didn’t think of the environment that much.”

His second step, he said, came when he watched a Sundance – a Native American spiritual ceremony where participants pierce their flesh with roped hooks tied to a tree. They perform ritual dances around the tree until the hooks fall out.

“You cannot bring negative thoughts to a Sundance,” he said. The experience changed his thoughts on his lifestyle, and led him to horses.

“My mother roped me in again,” he said. “I kept meeting people active against pipelines.”

She introduced him to a horse whisperer, not far from Camp of Standing Rock. There, he learned how to approach a horse, how to groom them, how to saddle a horse, and how to ride. He now owns a two-year-old Blue Roan named Guardian, part Dakota, part Choctaw. It was after learning about horses that he decided to become involved in his second pipeline fight, the Dakota Access Pipeline. What was supposed to be a short visit has become a struggle he will not leave until it is finished.

At first, no more than fifteen people lived at the Camp of the Sacred Rock. With only USD 3,000 in support, they watched the excavators push aside what was once their tribe’s soil.

“We couldn’t do anything at first,” he said. “We didn’t have the numbers.”

Sometimes Americanhorse went for two days without sleep. Camp life is hard, especially as their numbers grew quickly through the popularity of social media. Daily, he and others ensure activists have shelter, warmth, food, proper tents, firewood, and clean water. A school for children has been setup, a library as well. Medical crews are on constant standby to help the elderly or the sick. The Dakota prairie is mostly barren of vegetables and trees, so he gathers driftwood for fuel, and depends on donations to survive.

Smaller camps along the so-called front lines have been setup. Before sunrise, September 8, activists wearing bandanas over their faces returned from scouting maneuvers along the pipeline’s planned route. Some activists burned braided sweetgrass and waved the smoke over themselves before missions; for the company was watching them, just as they were watching the company, activists said.

They're organized, committed, and prepared to be arrested.

Rope stretched across the highway was used to slow traffic. Any fence knocked down was quickly rebuilt. Trash was collected in buckets. Porta-potties, food, and much needed coffee were brought from Big Camp to keep the front-liners as refreshed as possible. During the quieter times, some along the front line nap, or read books. Others warm themselves around a fire sipping hot drinks and discussing recent events. Any time a two-way radio growled to life, they become instantly alert, listening for action.

Despite the hardships of camp life, or perhaps more appropriately because of it, Americanhorse found his calling.

“Being out here made me want to be more involved in this life. I want to bring our culture back to the people, our ways of life in modern day.”

He has also learned that not all white people are racists. In addition to the thousands of Native Americans, others from all walks of life have begun committing their time, money, and for some, their personal freedoms to protect water, and now indigenous land. “It has been through fighting pipelines that I learned to be more open minded to everything.”

Like all Native Americans, Americanhorse understands oil is important to modern society. He knows that oil also must go from point A to point B, to be refined, and then shipped across the globe. But Bakken crude will never travel under the Missouri River, where Dakota Access plans the pipe to run. More monies and research needs to be poured into alternative forms of research pertaining to solar and wind powers, he said, instead of bolstering a dangerous addiction to fossil fuels with a pipeline that will one day leak.

“You cannot ignore this many nations coming together,” Americanhorse said. “You can’t see that and challenge it. This billion-dollar industry has never seen anything like this before.” Losing this fight, for Americanhorse, is not an option.

“There are more people involved in this fight than you know, and this pipeline is affecting a lot of people.”

Some of the activists are weekend warriors. Some are drifters, traveling by car, by bus, by hitching rides. Others like Richard Fisher, half African American and half Native American, gave up his 19-dollar-an-hour job in Sisseton, South Dakota to volunteer in the camp’s kitchen.

“I was born for this,” Fisher said. He stirred a cauldron of chili for the camp’s evening meal. “My dad was a Black Panther and my mother was with AIM.”

One of the camp’s head chefs and a traditional cook, Winona Kasto, is in charge of feeding any hungry mouth that comes her way. “It’s never ending, but it’s not tiring,” she said. “I came here because of the need to feed the people.” Usually, Kasto cooks wojapi, or a berry pudding, prepares dried squash, dried corn, stews, traditional native food, and in her spare time, if she can find any, holds classes for the youth to learn old indigenous recipes.

Americanhorse has given up his old way of life as well and returned to one much older. When there are no more pipelines or other issues to fight, he plans to raise horses, help his mother on her ranch where she owns breeds whose bloodlines can be traced to Sitting Bull’s herd.

Everywhere in the camp people are smiling, introducing themselves. Children play cops and robbers, volleyball, basketball to pass the calmer moments. Native American drummers sing traditional songs from all corners. At night, dozens gather around the fire at the Sacred Circle to pray and dance, a tradition that was once banned inside the United States.

“This is a very historical event, foretold by our elders that the Seventh Generation would rise up,” Layha Spoonhunter, an eastern Shoshone said. “We are seeing that here, and in many ways, we’ve already won. We’re going to win with the prayers and the songs that have been offered here, that is our strength and that will take us to victory.”

“The drunk Indian is dead,” Americanhorse said. “There are a lot more people going in the cultural ways. I see the healing. I look forward to seeing other cultures come up and bring their structures up, and that way witness other cultural presences from every other nation.”

Americanhorse’s story is endemic among many Native Americans gathered outside of Cannon Ball. Far too many appear to come from troubled childhoods, addictions, and are searching for identity. Their stories are told nightly around the Sacred Fire. They are returning to their roots and ancestral traditions, and discovering for the first time a peace they’ve never known before, while at the same time learning to accept all cultures.

December 16th 2025

November 14th 2025

October 13th 2025

October 13th 2025

October 6th 2025

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)