Cinema | September 27th, 2017

“Strong Island,” Yance Ford’s vital cinematic elegy to his slain brother, is a gripping documentary presented with control and precision. That careful formality serves both the story and the filmmaker’s underlying thematic questions addressing the absurd but commonplace outcomes of the notion of justifiable homicide and the use of reasonable fear as a means for perpetrators to claim self-defense.

In 1992, Ford’s then 24-year-old sibling, William Ford, Jr., was shot to death by Mark Reilly, a white mechanic. Even though Ford’s close friend Kevin Myers was nearby, the killing took place out of the direct sight of any potential eyewitnesses.

Statistically speaking, it was unsurprising when an all-white grand jury decided not to indict Reilly. Ford’s incredulous family members, initially expecting that a criminal case would be brought forward, speak about the slow-motion devastation of the system’s injustice and the effective destruction of their nuclear family in the months and years that followed.

Yance Ford, who often appears on camera in tight close-up shots, intimately processes his thoughts to articulate the impossible: “I’m not angry. I’m also not willing to accept that someone else gets to say who William was. And if you’re uncomfortable with me asking these questions, you should probably get up and go.”

Calls are made to several of the people involved with the original investigation, and Ford uses those conversations to underline the common way in which power is exercised against the marginalized.

But as the narrative unfolds, the filmmaker stakes out and clarifies positions that don’t rely on the procedural (mis)handling of his brother’s case: Ford said in an interview with Steve Rose, “I have no interest in giving Mark Reilly any space in this film. When you shoot my brother, you’ve said everything to me that you have to say.”

Instead of orienting in the direction of any lurid, true crime rundown of reported details, Ford makes some bold and rewarding choices. The insidiousness of zoning all African-American neighborhoods inside Long Island is expressed by Ford’s matter-of-fact narration and through the words of Ford’s mother Barbara Dunmore Ford, who leaves a lasting impression on viewers through the vivid detail and specificity of the anecdotes she shares.

Dunmore Ford’s presence in the movie is indispensable, and the way in which she addresses the toll of grief on her marriage results in one of the movie’s most unforgettable scenes.

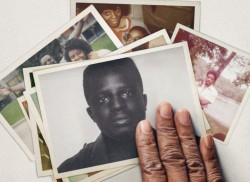

Additionally, Yance Ford personalizes the loss of his brother by including a series of snapshots and photographs, physically arranged by hand within the frame (home movie footage is also incorporated, but to a lesser extent). The visual device calls to mind, among others, Daniel Lindsay and T.J. Martin’s stunning 2013 short “My Favorite Picture of You.”

From start to finish, Ford spent more than a decade on this project, and the full weight of its considerable impact lands with the filmmaker’s grim reminder that the conversation about violence against unarmed African Americans must be expanded beyond the coverage of police incidents to account as well for civilians who get away with murder.

February 16th 2026

February 16th 2026

February 9th 2026

February 4th 2026

January 26th 2026

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)