All About Food | June 19th, 2019

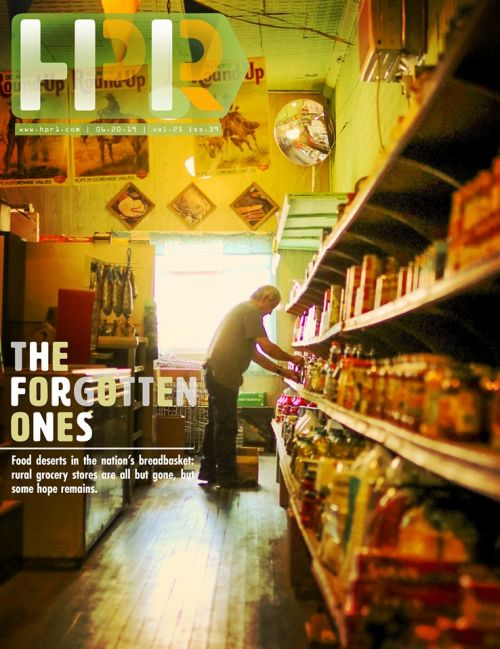

PETTIBONE – Terry Gruebele filled his arms with canned corn – the state’s favorite vegetable – from a cardboard box below long, warped shelves. After 33 years of running T & V Grocery Store, he’s watched the rural exodus, and now counts his pennies to make sure bills can be paid.

He knows the family store with its near 100 years of history is most likely doomed. Nobody will take over the business when he and his older sister are done. Logistics is difficult. UPS ships potato chips. Milk, produce, cigarettes, and soup-in-a-can deliveries come once a week. Some meat – like the ribeye steaks advertised in the store’s paper – is from local butcher shops, but he has minimum quotas, delivery charges, and faces higher costs just to get most of his stock delivered.

He finished restocking the corn, and turned to sauerkraut, redolent of how the old lunch counter is gone. The town hall with its dances, movies, and performances is quiet. Pettibone residents – population 70 – are growing older, but Gruebele doesn’t plan on quitting. He and his sister inherited the store from their parents, Louie and Violet Gruebele.

“Sometimes it gets pretty tough,” Terry said. “It’s almost a hand-to-mouth living. If people would come here instead of going to Walmart, things might be different. There’s just nothing to keep the young ones here.”

His sister and business partner, Verleen, sat at the cash register, mostly silent other than to say come hell or high water she’s in Pettibone to stay. She’s free in the countryside; she can do what she likes.

The building has changed hands and names repeatedly since the Roaring ‘20s when it first opened as the Consumer’s Store selling everything to survive the harsh frontier – clothes, boots, tools, saddles, guns, ammunition, hot soups and sandwiches, and of course, groceries. Vintage tin panels still decorate the ceiling. The hard oak floor is worn in places, but clean, and still sturdy.

At the store’s front, sepia-toned Del Monte Round-Up hanging signs advertise cowboys on horseback lassoing cattle.

“Rope in storewide values,” the posters read.

Because logistics are difficult and the Gruebeles can’t order much in bulk, Terry and Verleen’s store values can’t compete with mass market retailers such as Dollar General – a name spoken with no small amount of spite in rural towns – or even Costco, or Walmart. Inside T & V Grocery is a whole food desert: amounts of fresh produce and fruit at T & V Grocery pale in comparison to the quantity of canned beans, boxed cereals, and other non-perishable items. Farmers and others living in the countryside can’t afford a sense of brand loyalty. Hard times are forcing residents to go where goods are cheapest.

In a Facebook-less land of flip phones, relationships are king. But when once aspiring towns that held populations in the hundreds now have 50, or 40, or even less, relationships only go so far to keep a family fed. With 42 percent of North Dakota towns having less than 200 people, many residents seemed resigned that small town USA is slated for the history books.

Morning coffee crowds grow smaller. The median age in the countryside is growing older, decades over the state median age of 35.2, according to the North Dakota Census Office. Hunters buy up properties to sit on them as tax deductions or as seasonal lodgings, residents say. Many hunters bring their own food, offering little financial assistance to the struggling businesses that remain in local communities.

Out-of-state hunters have also caused another problem in rural North Dakota: there are little to no properties left for interested newcomers – young blood – to buy.

“A lot of the places are just one step away from not existing,” Robinson Mayor Bill Bender said. “Winters are extremely tough and getting tougher with Trump’s trade war. People are holding back on expendable income.”

For a small fee Paul Geringer has been driving a bus for the aging rural population in Kidder County. He drives them to the doctor’s office, to the bank, or to the grocery store, which for some could be a half-day round trip.

“I will tell ya, I’ve been doing this for going on 11 years and my riders are down to less than half,” Geringer said. “The biggest share of them are elderly, but we can haul anyone who wants to go. Some of the towns are about half of what they used to be. Grocery stores in the past several years, well, they’ve diminished. Post offices have closed up completely, or are at half days, and our banks have done the same thing.”

Except for new industry bringing jobs, Geringer doesn’t have any ideas on how to revive rural North Dakota.

“Our population is going downhill, and I think it’s going to be a continuous trend for a while,” Geringer said. “We got a quite a few elderly people, they end up in the nursing homes or are passing on and it makes for a bad deal.”

Last March, 124 rural grocery stores were operating throughout the state. Since then, five more have closed or are planning on closing their doors, state Senator Jim Dotzenrod, a Democrat, said.

Twelve miles away in the town of Woodworth – population 48 – Pam Mahuttga manages the Woodworth Café, home of the “Woodworth Whopper,” which also offers limited grocery items. She returned to her roots after a divorce, and loves the quiet of the countryside.

Mahuttga took a large salary decrease in accepting the job, but she feels safe and at home in Woodworth. Outside the café, which features a veterans wall from men who served from Woodworth, mourning doves coo and milk cows low. The sweet smells of sweetgrass, honeysuckle, and wildflowers filter through the early summer breeze. Bees and dragonflies flit lazily through clover patches.

No one is honking horns. Train whistles no longer exist. Police sirens? Horses munching hay a stone’s throw from downtown Pettibone have probably never heard the sound.

“As you can see this one is almost gone,” Mahuttga said. “It’s a real struggle day to day. They were ready to close when they hired me.”

The building was once a true grocery store, but now it’s a café with items like milk, cream, bread, and soda. The town was more active before the school closed, even before the train stopped arriving at the nearby grain elevator. Unless a neighbor needs milk during a snowstorm, she closes at 2 p.m. so she won’t have to compete with the bar next door.

To make ends meet she’s linked up with First Responders Class, tries to personalize her customers’ dining experiences.

“I think most of the women work out of town, so they pick up things in the big town,” Mahuttga said. “It’s kind of fun coming here and I want this community to be something. It was when my mom was little. I hope it will again.”

A former café manager, Cheryl Buskness, came in to the dining area.

“This guy is doing a story about dying grocery stores,” Mahuttga said.

“You’ve come to the right place,” Buskness said. “Now there isn’t enough people. I don’t know if we will ever get the people to come back, I don’t know if it will ever be enough.”

Buskness moved away after she quit managing the café, she said, but returned.

“I could not wait to move back,” she said. “Last few years little kids are starting to show up, but if you don’t make the money in farming you can’t stay. Here, most of the wives even work on the farms, they can drive any of the equipment.”

Carol Steichen of Carol’s Kitchen in Robinson pushed buttons on the cash register before looking up.

“Want something to drink?” she said.

“No, thank you.”

“Cheap.” She offered a disapproving frown before a warm smile.

For 15 years Steichen has managed the café that prides itself on its Knoephla soup, a winner of the 2016 ‘Hole In The Wall’ Restaurants In North Dakota That Will Blow Your Taste Buds Away title.

Her main problem is deliveries. US Foods, a food shipping company, charges her $5 a stop, but she has to order a minimum of six items. When the transportation company wanted to add an additional $7.50, she said no more.

“This is a small community, I mean seriously,” Steichen said. She can buy fries from Sam’s Club in Bismarck for approximately $17, but US Foods charges her $27, she said. Same for vegetable oil. At Sam’s she pays about $19, but US Foods wants $23 and $41 for a five-pound bag or red potatoes.

US Foods is the only distributor she can call for deliveries. They have a virtual monopoly on the rural market, she said.

“They got me by the throat.”

A December 2017 North Dakota Rural Grocery Initiative report aimed at improving rural access to food distribution resources is the data behind a legislative resolution set for discussion in 2021. Food wholesalers have 64.3 percent of the market while small local food growers have only 1.7 percent. Nearly all the goods purchased by grocers were processed foods from mass-market wholesalers such as Frito Lay, Nestle, Old Dutch, Sara Lee, US Food, Pepsi, and Coca Cola. Most of the rural grocery stores surveyed said their prices were too high to be competitive.

Rural grocery stores rarely sell locally grown food, and those that do primarily sell fruit, vegetables, and baked goods. Farmers target larger distribution routes.

Additionally, half of the rural grocery stores participated in public health and anti-hunger programs with their clientele, according to the report.

The Rural Grocery survey – which had 52 out of 127 grocery stores participate in 2017 – indicated that rural grocers appear to be happy with their deliveries, but not as satisfied about pricing. Since the time of the report, however, a total of eight stores have closed or will be closing soon leaving 99 operational in rural North Dakota.

“It’s five years ago we started getting phone calls from rural grocery operators and the first one was like ‘Do you know any grant programs that could help us cover operating shortfalls?’” Rural Development Services Director Lori Capouch said. She’s with the North Dakota Association of Rural Electric Cooperatives.

“And so I am a rural developmental professional and that is one of those scary phone calls. You know that they’re not going to make it. There is no grant money for that.”

Soon after the initial telephone call, more concerned grocers began calling in.

“We started doing some research and discovered that something has shifted in the industry,” Capouch said. “Why all of the sudden are we getting these phone calls? We learned that it’s a rural problem across the country and that other states were also researching this.”

The problem was daunting. Living in food deserts shows it is far more expensive to be poor than to be rich, Capouch said. Limited access to quality food affects healthy lifestyles, which in turn can have serious repercussions to physical health. In North Dakota’s countryside where rural hospitals are struggling and closing doors, where trade wars are keeping farmers anxious, grocery stores could shrink in importance.

But then again, everyone eats, and healthy lifestyles begin with affordable access to quality foods.

“You hesitate to take something on so big because most definitely it’s population decline,” Capouch said. “But we decided to dive in and start talking to the grocers.”

She began collecting data and mapping the suppliers – “connecting the dots” – and was surprised to find out that for small volumes of food there was inefficient distribution based on a purchasing tier system that criss crossed each other, forcing costs to rise.

“If we could just help them map it,” Capouch said. “There has got to be a way to streamline the distribution.”

Questions Capouch is trying to answer include: Can we streamline the distribution? Is there public infrastructure we can partner with to bring the costs down? Are there policies that add difficulties to rural groceries that need to be changed?

Capouch turned to the Upper Great Plains Institute who helped optimize routes, which would save up to $380,000 in distribution costs, she said.

“How you capture that would be key,” Capouch said. “It’s hard to convince people to collaborate or to take a risk or change how they’re doing things, but we do have three stores willing to try it.”

Most grocers in rural North Dakota average $20,000 in gross sales per week, which leaves approximately $18,200 in net profit at the end of a year, Capouch said.

“Some people pay themselves after the net profit margin,” Capouch said. “Nobody is getting rich.”

State Senator Jim Dotzenrod took a break from late spring planting near Wyndmere to discuss a bipartisan resolution he helped sponsor during this year’s legislative session.

“It’s been a concern that I’ve heard from people and legislators over the last few years but no one has tried to really figure it out, or maybe they have, but the answers are not going to be easy and obvious,” Dotzenrod said. “It may take some experimenting.”

Solving the issue of vanishing grocery stores could be a starting point for facing other rural North Dakota’s ailments, including lack of health insurance and hospitals, emergency services, transportation and distribution, among other issues, Dotzenrod said.

“I think we’re finding this is going hand in hand with the other issues that deal with the quality of life,” Dotzenrod said. “There are a number of things that seem to be quality of life issues and we may see over the next 20 or 30 years the movement of rural North Dakotans to the big cities continues unabated. And that’s hard for me as a rural person to accept that.”

Some areas in North Dakota are succeeding; younger people are no longer strangers, Dotzenrod said. At the same time towns nearly gone are vanishing even further. Home values are decreasing offering those that remain little hope. Seasonal farmers and hunters are no longer integral parts of rural community life; they come to make money or have sport – then leave.

A farmer’s life isn’t as isolated and harsh as decades ago with air-conditioned tractor cabins, power steering, and one the nation’s best rural Internet services, Dotzenrod said. Technology may have made the world smaller, but 30 miles to the nearest grocery store for eggs and a jug of milk in the dead of winter is still a dangerous and perturbing prospect.

“There are a lot of question marks on where we are going to be 20 or 30 years from now,” Dotzenrod said. “It’s a puzzle. There’s a lot of anxiety about where our state is going.”

Legislators are called upon to study the resolution over the interim and find ways to help rural grocers and communities, Dotzenrod said.

“I’m looking forward to the study,” Dotzenrod said. “I hope we can identify where it is that we are going backwards. Is it a generality we can make of the whole state? I don’t think so.”

Lori Capouch expects some political resistance to future legislative changes regarding collective purchasing.

“Policy makers will say they don’t want to interfere with free enterprise,” Capouch said. “My counter argument to that is that suppliers will continue to supply if the price covers their bottom line, and I am not faulting them for that, it’s a business, but it’s coming off the backs of people… who are converting to community owned. There are volunteers who buy food at Walmart and stock it on their shelves. There are volunteers that are unloading the trucks, and there are even volunteer store managers.

“I think it’s hard to go run and get milk after work when I am tired, but at least I don’t have to work at a store. So what we are not capturing is that there is a huge cost to it, to make it affordable in their communities they have to volunteer to make that food available.”

One policy needing change at a federal level is the WIC Assistance program, or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. The program provides food to pregnant women or new families, but also stipulates that a community must have at least 15 infants in order to qualify.

With 42 percent of North Dakota towns having less than 200 people current stipulations are difficult to meet, but if changed, grocery stores could become involved with WIC and similar programs, Capouch said.

“Let’s notice this before it’s too late and we lose that infrastructure completely,” Capouch said.

In order for rural communities to return, residents must have access to education and healthy food.

“Those are the things that rural people fight the absolute hardest for,” Capouch said. “If we could keep those basic needs, I feel like people will be looking for a quieter way to live.

“It’s like a puzzle that can keep you up at night trying to solve it.”

Carol Steichen’s busiest time of the day is dinner. Business is dwindling, but with a monthly rent of $100, better distribution and prices, she could make ends meet if she had no other obligations. She cooks because she loves it, and she’s a people person. When she’s not busy flipping burgers or making her famous soup she bakes buns and breads, caters parties, and works the family farm.

“We are all getting older,” Steichen said. “We’ve been farming for 40 some years. What are we going to do when we retire? It is what it is here. If I don’t make $100 a day here I am in the hole. You got to have a personality to be in the café business, you have to have P.R.”

Mayor Bill Bender was working outside building tables in the beer garden of what was once the town’s blacksmith, then millinery, now Hanson’s Bar, also the registered geographical center of North America, aka: the “Last Bastion of Manhood,” the “National Bar of North Dakota,” and “North Dakota’s Oldest Bar,” having been established as a tavern in 1936.

“If there was money to be invested to renovate the older houses I think that would be attractive to some people, especially snowbirds,” Bender said.

Inside Hanson’s Bar, the smell of Grandma’s attic, but it’s clean with daguerreotypes and historical eye candy covering the walls. To make ends meet Bender features two live music stages and hosts festivals every year including Center Fest, truck pulls, and the Miss Center Fest Pageant.

The local Lion’s Club is also an integral organization in helping Robinson’s economy, Bender said.

“It’s just a matter of getting people in,” Bender said. People from Bismarck, Fargo – even Colorado and Indiana – drive to attend his summer bashes. “Keeping the café open. Keeping the bars open. You can have no mortgage in these towns.

“It comes down to price,” Bender said. “And it’s all about helping out.”

February 23rd 2026

January 12th 2026

November 18th 2025

November 12th 2025

September 16th 2025

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)