News | April 25th, 2018

GRAND FORKS – Residual racism is a leading reason why the University of North Dakota plans to demolish the last brick-and-mortar remnants of Wesley College, some historians say. Wesley College, a former Methodist school, merged with UND in 1905, becoming one of the first American marriages between a religious college and a state university.

University personnel say racism has nothing to do with the upcoming changes, but that budget cuts and financial necessity are forcing tough decisions.

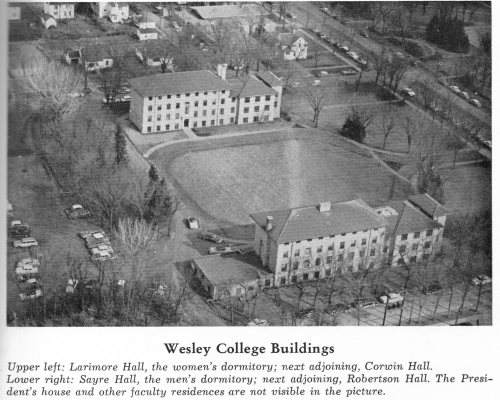

The buildings slated for demolition next month include Robertson/Sayre Hall and Corwin/Larimore Hall. Sayre Hall was built in 1908; Robertson Hall, named after an early Wesley College president, Edward P. Robertson, was finished in 1930.

The two-school affiliation lasted until 1965, when Wesley College trustees agreed to sell its buildings to UND and change its name to Wesley Center of Religion. The last remaining properties adjacent to UND were sold in 1968 and 1973, and the Wesley Center relocated to Wesley United Methodist Church in Grand Forks.

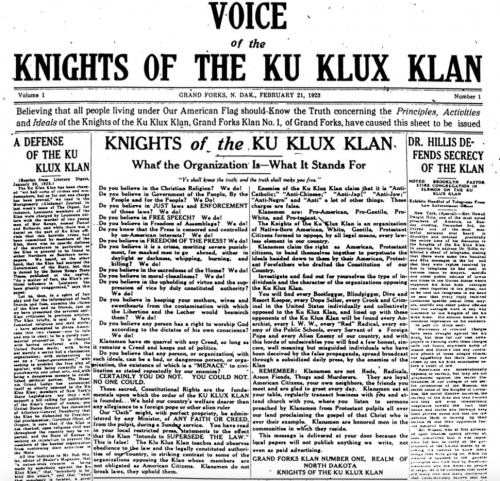

After the merger, Wesley College was the more liberal, and stood behind Methodist Reverend George Henry’s fight against Presbyterian Reverend and rumored Ku Klux Klan Exalted Cyclops F. Halsey Ambrose. The Klan rose to power in the early 1920s in North Dakota, winning municipal elections and capturing the Grand Forks school board in one of the largest votes in the city’s history. In 1926, Klan forces made a clean sweep in city elections as well.

The relationship between the two colleges was always tenuous, at best, according to historical records. When the Ku Klux Klan rose to power in the 1920s a “music war” followed between the already existing Wesley College Conservatory and Ernest H. Wilcox, described as a visionary with powerful friends. While Wesley College had a robust music program with renown teachers, UND competed by offering free lessons and easy grades, crippling their religious partner.

“In modern times, we need to remember people and institutions with the courage to oppose the forces of intolerance,” historian Andrew Alexis Varvel said. “This coming June, the University of North Dakota is prepared to demolish the last vestige of a stronghold against Klan ideology, erasing a reminder that there once had been resistance against the Ku Klux Klan. Destroying these buildings would send a clear message to the Alt-Right what the University of North Dakota's priorities really are. I call upon the University of North Dakota to stop the slated demolition of these buildings and instead restore them to their former glory, so future generations will be reminded what courage looks like. And I call upon anybody who is willing to speak out and do what they can to save these buildings to do so now, while there is still time.”

The buildings are structurally sound, but have been mostly vacant for a year. They are part of a set of 13 buildings being pulled down in compliance to a “master plan” for the entire campus. Both buildings were listed in the National Registry as part of the North Dakota Historic District in 2009, Lorna Meidinger, an architectural historian with North Dakota Historical Society, said.

Meidinger hasn’t seen the press release from the university saying demolition is on schedule, but, “every indication that I have from them is, yes, they are tearing them down,” Meidinger said.

The two buildings are impressive Gothic structures, multi-storied, with stone windows, decorative brick exteriors, and hints of Colonial and Tudor Revival shaped in Beaux Arts form. The most significant periods for the buildings were between 1883 and 1965, and they both embody distinctive characteristics of the time, according to the University of North Dakota Historic District paperwork.

Built by J.B. DeRemer, reportedly one of “the finest architects in North Dakota” who was also involved in architectural wonders including the North Dakota State Capitol, the Art Moderne United Lutheran Church and the B’nai Israel Synagogue in Grand Forks. Many are hoping the buildings can be saved.

Both Wesley College buildings were used primarily as dormitories, and had famous North Dakotans including aviator Carl Ben Eielson and lumber baron Harold Holden Sayre, for whom Sayre Hall was named after, living in them. All students at UND or Wesley College lived in the dormitories, according to university architectural historian William Caraher.

Sayre was a men’s dorm, Larimore was the women’s dorm, and Caraher has been spending the last few weeks with students documenting, photographing, and studying the buildings and their former occupants.

“They’re part of the fabric and history of the university,” Caraher said. He would like nothing better than a plan and the money to save the buildings, but with recent 10 percent budget cuts to universities and facing difficult financial times, hard choices had to be made, he said.

In essence, the buildings are too expensive to maintain, and bringing them to modern standards isn’t affordable.

“The temptation to make UND out to be the villain is easy,” Caraher said. “But UND is sort of the hero in this too, they could have made this quietly go away, but they didn’t. They really tried to do everything right.”

“College campuses are a lot like downtowns,” Caraher said. “We love old buildings, but we also love parking, we love bike lanes, all of these things have to be balanced. A town can be quaint and cute, but you want state-of-the-art classrooms, and offices, and rooms good for teaching; and these rooms just aren’t that anymore.”

Caraher has heard of the racial motivation behind tearing down the buildings, and knows of the former tension between Wesley College and UND, but said those are not the reasons for the demolition.

“Most of the tension rose around music,” Caraher said. “UND ended up eating -- I don’t want to say cannibalizing -- but eating up Wesley College’s income from that. And I admire Varvel’s effort to historicize these buildings in that way. College campuses always have traditions and stand as symbols of progress. Traditions are great, but you don’t want to walk into a computer room and use a Commodore 64, nobody wants that. There’s always been this tension between needing to be progressive and the need to preserve.”

Meidinger agreed with Varvel that residual racism could be unconsciously at the issue’s core.

“I’ve never heard it from anyone on campus as part of this history – very specifically – but it’s one of those items that I’m not surprised,” Meidinger said. “They don’t want to project that part of their history. They may have not wanted to project it in the past, or have selectively forgotten, or these new individuals who are there now might not know that portion of their history.

“If UND wasn’t there, and those buildings still were, they would still be eligible to be on the National Historic Registry,” Meidinger said.

The technical director for Theatre Arts at UND, Loren Liepold, said he also agrees that some form of residual racism may be at the core of tearing down the buildings.

“The fact that happened makes for some fantastic history, but my motivations are a lot less racially interested,” Leipold said. “Mine goes back to this legacy the state of North Dakota was given.”

On occasion, he visits the fourth floor of one of the buildings, and muses one day soon it may all be gone.

“It still has that dorm feel, you hear the echoes and you see the doors that have been there for so long, and that’s part of the university education for a student to come in and have a wide range of choices. It frightens me to no end that our students aren’t going to have those buildings.”

What worries him even more is the university’s overall strategic plan includes tearing down many older buildings. Montgomery Hall and Chandler Hall may be next, Liepold said.

“I know there is a movement to try and save it and I sure hope they can,” Liepold said. “The university and the state are so focused on cutting budgets, no one will take a moment and see how can we save this. It just screams to me that we aren’t seeing the worst of it yet.

“We owe our heritage a little bit of a chance to keep having a heritage.”

The associate director of construction management for UND, Brian Larson, said demolition plans are on schedule to begin in June.

“I think it’s time,” Larson said. “The buildings are vacant, the departments in those buildings were moved into more modern buildings on campus and it really made sense to move these departments out of the buildings.”

The old dormitories are not up to modern code, he said. One has no elevator system, neither have sprinkler systems installed.

“It’s just about impossible to make these buildings compliant with regulations, and they aren’t conducive to shape modern classrooms,” Larson said. “We’ve done a lot of efforts to preserve the buildings, and document the buildings prior to demolition. That’s been a wonderful experience.”

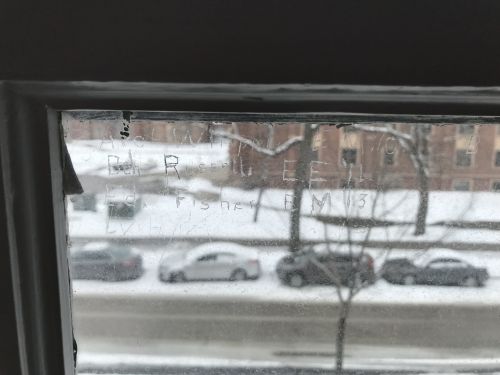

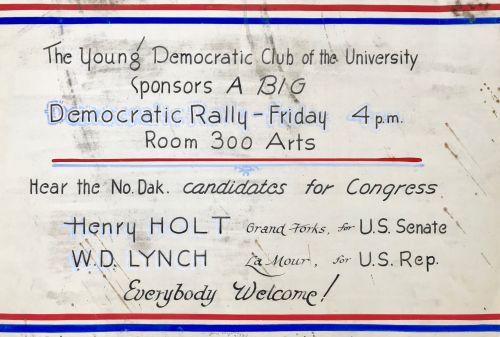

A handwritten political poster from 1934 was found behind an old plaque, and names etched in glass led to the discovery of one graduate, Archie Whipple, class of 1910, who went on to be head of grounds on the UND campus before moving to Kentucky.

Some of the efforts to preserve their heritage include hiring a photographer, perform a full 3D scan of the building for future models, and hired a drone company to document the buildings by doing flyovers. Although other historic buildings including Chandler Hall are slated for demolition this year, the campus plans to preserve a handful, including Merrifield Hall, Larson said.

As for the accusations of racism, Larson said he wasn’t qualified to answer, but added that “UND is opposed to anything to do with the Ku Klux Klan.”

Interim Vice President at UND, Peter Johnson, said the decision to tear down the last remaining buildings of old Wesley College was not an easy one to make. A memorial will be erected commemorating the buildings, he said.

“There are a number of reasons,” Johnson said as to why the buildings are going to be demolished. “The state government went through a series of cutbacks, and for UND that meant we had to reshape our budget by $50 million.”

The university also had nearly half a billion deferred maintenance costs it could not keep up with, Johnson said.

“We’ve been dealing with some pretty serious cutbacks, and what’s that meant here is the loss of jobs for people and some minor pragmatic types of cuts. So we’re dealing with how do we manage the budget we have with the budget we have.”

Johnson is aware of the Ku Klux Klan’s history in Grand Forks, but wasn’t sure of Wesley College’s fight against them.

“There’s no question that in the 1920s that there was a strong Ku Klux Klan presence in Grand Forks,” Johnson said. “I certainly hope that it’s true, that the leadership of Wesley College took a stand against the Ku Klux Klan, and maybe those are some of the things that we may need to commemorate, but I don’t know how the buildings commemorate this.

“What’s the best way to memorialize what they want to memorialize? Is there some other way for people to be mindful of that history?”

Varvel hopes the issue can be discussed, and plans to attend a meeting with the State Board of Higher Education this week to make his case, he said. He doesn’t expect the university to fund maintenance, but wishes to discuss options.

The buildings are not only structurally significant, as UND’s campus is host to generational architectural differences, but the structures stand as the area’s final bastions against hate and as reminders to those who took a stand against rhetoric of the 1920s, which closely mirrors today’s political world.

“The Wesley College Conservatory brought great musical artists to the community, and its religion classes promoted mutual respect among religions,” Varvel said. “The Ku Klux Klan and its leader Halsey Ambrose were ideologically opposed to everything Wesley College stood for, and vice versa. The 1920's were an era when ideological racism was popular in both politics and academe, fascism was on the rise, and religious bigotry was trendy. The Ku Klux Klan would conquer city government and launch a purge, but Reverend George Henry took a stand against it at a time when it mattered.”

Grand Forks’ racial tension

The university’s lack of backbone against racism began with donations from railroad tycoon and “empire builder” James J. Hill to UND and Wesley College, who in the early 1900s considered North Dakota a “hostile state” when asked to promote Wesley College, according to historical documents. Hill also considered Swedes to be the only hardworking employees, and encouraged them to migrate west along the Great Northern Railway, which Hill owned.

The school’s former mascot, Fighting Sioux, was considered a degrading symbol by many, and was changed in 2015 to the Fighting Hawks. The fight for that change however was arduous, with the university frequently giving into demands from longtime supporter Ralph Engelstad, for whom the Ralph Engelstad Sports Arena at One Ralph Engelstad Arena Drive was named after.

Former UND student and Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s Vice Chairman, Ira Taken Alive, remembers when in the 1990s he fought against the university’s use of the Fighting Sioux mascot.

“If I recall correctly I was one of the first Native Americans to serve on the UND Student Senate, and when the issue of the Fighting Sioux nickname came up, during the episode of my time, I think a lot of Natives were forced to have an opinion on the issue, and that was certainly my case.”

Because of his role in school politics, and because he worked at the cafeteria, Taken Alive became the face behind the issue, he said.

“People associated me with the issue, thereby I received several anonymous emails stating their disgust and that really pushed me to get active about changing the nickname. I was forced to take a side.”

And then his car was vandalized. Instead of fighting back with protests or sit-ins, Taken Alive and other students took the issue to educational forums, and then to the state legislature, which ignored them until Engelstad threatened.

“Once Ralph Engelstad made his ultimatum that he wasn’t going to be building his hockey rink, then the legislation acted. It was discouraging because we were given so many smoke screens.”

Looking back at his time at UND he said the experience wasn’t all bad. After a brief-but-needed transfer to another college, he returned to graduate, but the university does need to come to terms with its past, Taken Alive said.

Occasionally, he reads newspaper reports about Native students being harassed in the dorm rooms, or mistreated because of their race.

“I can say this,” Taken Alive said. “I’ve been disappointed that recent statistics show we’ve had five or less students from Standing Rock attend UND, and I do know having several conversations with fellow tribal members from Standing Rock that they had considered UND, but due to the perceived racism there, they chose NDSU instead. It’s a little disheartening as an alumnus, hopefully that gets better.”

Until today, the UND mascot remains an issue of dissent for many.

“Some people continue to support the ‘Fighting Sioux’ nickname at the University of North Dakota,” Varvel said. “They may not necessarily seek to dehumanize Indians, but they are heirs to a tradition of dehumanizing Indians that they refuse to give up. Nickname supporters contend that their beloved nickname is intended ‘to honor the Sioux,’ but original documentation of the nicknames adoption from 1930 makes it abundantly clear that a powerful clique imposed that nickname onto UND to appropriate ‘Indian medicine’ after UND's loss to the Haskell football team in 1929. That nicknames origin came from a conscious and explicit desire to counteract the Haskell football team's challenge to students' sense of white superiority.”

Engelstad was UND’s class of 1954, and a goalie on the UND hockey team. He made good in the construction business, and later with casinos in Las Vegas. Engelstad was also a Nazi buff who collected Third Reich memorabilia and celebrated Adolf Hitler’s birthday with swastika-decorated cakes. Servers during the parties wore T-shirts emblazoned with “Adolf Hitler – European Tour.” Engelstad was outed in the 1990s, lost his gambling license for a time, and rejected the claims that he was a Nazi sympathizer.

The university was included as one of those “Who Stand Firm on Weak Knees” by Spy Magazine, and believed Engelstad’s declaration that he wasn’t a Nazi, and continues to rent the self-named sports arena from the Engelstad family, despite the accusations that he held the university hostage during mascot negotiations in the 1990s. Engelstad was adamantly against any mascot change.

Grand Forks, as well as other areas across the state, has had a troublesome past concerning racism. As recently as 2016, racist social media posts from UND students have gone viral. Indigenous people have had beer poured over their heads and told to go back to the reservations. The lack of a backbone was also evident in 2013, when young high school students dressed in KKK hoods and attended a hockey game.

Today, director and membership coordinator for the American Freedom Party, formerly known as the American Third Position, a politically party initially established by skinheads, Jamie Kelso, of Grand Forks, works as a bullhorn for white supremacist ideals, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Kelso hosts “The Jamie Kelso Show” for the American Freedom Party, was once the personal assistant for former KKK leader, David Duke, and helped give rise as a moderator for hate-web guru Don Black’s forum Stormfront.

Kelso, 69, also filed paperwork earlier this month to run for the Grand Forks Public School Board.

“One of the reasons why racism has endured for as long as it has is because people continue to believe in its power,” Varvel said. “This is why connotation is so important – once people get suckered into believing that racism cannot be defeated, it won't be defeated. It is best to use the term ‘residual racism’ to describe the lingering effects of racist ideology from a previous era. It is best to avoid using the term ‘institutional racism’ because that term puffs up the perceived power of racism to such an extent that it could easily lower the morale for anybody who seeks to change the world for the better. Racism is institutional by nature. Racism is an institution for sorting people and organizing people collectively by race, often for the express purpose of creating a pecking order based upon racial appearance."

The idea of race is an institution itself, Varvel said. Individual racism rarely occurs without social approval, and is rarely tolerated without social acquiescence. Likewise, individual racism cannot flourish without legal sanction, and is typically a manifestation of corporate racism.

“In other parts of the world, the notion of a university (particularly a university that celebrates the legacy of a staunch admirer of Adolf Hitler) demolishing the last physical vestige of an ideological stronghold against the Ku Klux Klan would prompt a reaction,” Varvel said. “It might lead to rallies or nonviolent demonstrations. It’s hard to say what will happen in Grand Forks. This issue could be seen, in its own way, as a mirror image of the Confederate statue controversy elsewhere. In this case, it’s a matter of preserving an institutional monument of resistance against the firebrand preacher Halsey Ambrose and his Ku Klux Klan.”

October 13th 2025

October 13th 2025

October 6th 2025

September 29th 2025

July 29th 2025

_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)