All About Food | July 24th, 2019

FORT YATES – As a boy living near the Mníšoše, or Missouri River, ghosts surrounded Pete Red Tomahawk. Hungry entities that survived through the names of former oppressors: Yates, McLaughlin, Pick-Sloan. Even Morton County’s public health division – Custer Health – is named after the “Indian fighter,” Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer to present day.

A registered member of Standing Rock, Red Tomahawk and others have quietly resisted, using the name Long Soldier to describe Sioux County’s seat, Fort Yates – in memory of Captain George Yates, killed at the Battle of Greasy Grass in 1876. Across the border in South Dakota is the town of McLaughlin, named to remember the Indian agent James McLaughlin, responsible for issuing the arrest of Chief Sitting Bull. Marcellus Red Tomahawk, Sitting Bull’s murderer, is emblazoned on the sides of every state Highway Patrol car.

And then there is the Missouri River and the dams built strategically along its banks next to Native communities through the Pick-Sloan Flood Control Act of 1944, another federal project that scattered Native communities in North Dakota and South Dakota.

Until the 1950s, Standing Rock thrived along the Missouri River, tribal Chairman Mike “Buffalo Soldier” Faith said. Before the missionaries came to haul the children away to boarding schools and federal relocation programs dispersed many, he remembers life as a child surrounded by towering cottonwoods, juniper and buffalo berries, chokecherries, wild grapes, honeybees and deer.

Before the dams came, everyone shared chores. Some chopped wood. Others hauled water. Life was hard, no longer nomadic, but meaningful. The soil was black and sweet, perfect for gardening and lacking the salinity the soil has today. Many households in the bottomland had woodstoves cooking coffee, soups, round bread day and night. Guests were welcome to sit down and eat home-cooked meals at any time, Faith said.

The dams not only destroyed the Missouri River’s ecosystems, but devastated a people’s way of life. Over time and mixed with broken treaty promises, the dams left a food desert. Standing Rock, from the chairman to the elderly and the youth, is making plans to bring back food sovereignty. With cases of diabetes and cancer still rising on the reservation, their goal is to no longer be reliant on mass-produced food bought in bulk and sealed with nitrogen, formaldehyde, or additives harmful to humans.

“Before the dams were built everything was just like the way it was, with wildlife and trees,” Faith said. “Back in the day before the dams flooded and took away our lifestyles, it was peaceful. Everyone was living in harmony.”

“There was humor even in the bad times,” Red Tomahawk said. “As children, we didn’t know of the bad times. There were so many trees there at night it was pitch black being that it blocked the moonlight.”

Red Tomahawk lived along the Talking Stone River, or Cannon Ball River, but his grandparents’ home was along the Missouri. He used to swim the great river in the summers, and although the current had an undertow, it was much weaker before the dams were built. Today, much of the Missouri is too dangerous to swim.

“People had to relocate,” Faith said. “There used to be millions of trees all along the river. It just shows how destructive the Pick-Sloan Act was. They didn’t want to move, but they were standing in water.”

“We were the grandchildren back then,” Red Tomahawk said. He suffers from diabetes and is a cancer survivor. He has already lost two sisters to the deadly disease. “Now we are the elders. By us doing this we will be able to survive another 100 years or more.”

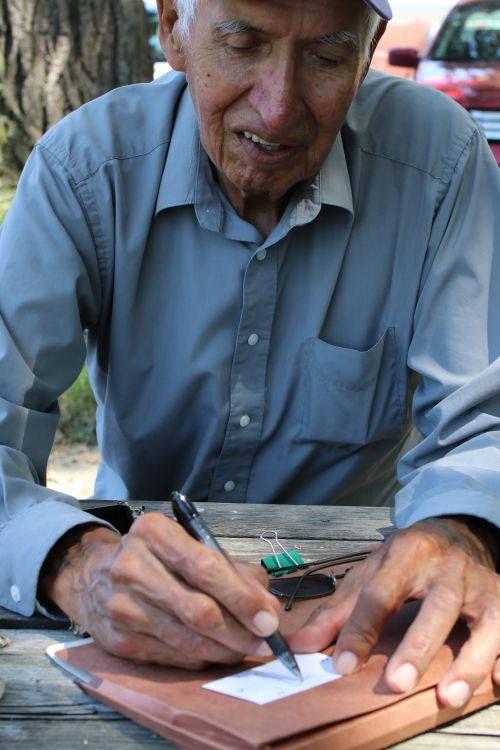

Retired from being the director for road planning on the reservation, Red Tomahawk, and others are bringing back the old ways handed down by grandparents through stories and teachings. They’re also open to partnerships and new agricultural methods and alternative energies needed to help sustain food sovereignty.

Today’s unhealthy diets of convenience – fast food, prepackaged foods – have sent cases of diabetes and cancer in Standing Rock skyrocketing, making tribal food sovereignty more important than ever before. Statistics from the National Institute of Health report diabetes has increased dramatically at Standing Rock over the past 30 years and that Natives are 3.44 times more likely to die from diabetes than Caucasians living in the same area.

A severe lack of health care clinics because of its remote location is another contributing factor, according to testimony given by Brandon Mauai on June 28, 2018 before the Healthcare Reform and Review Committee.

Health begins with a proper diet, Red Tomahawk said. He thought he was living fairly healthily before contracting cancer, but he knows now he wasn’t. His diet has changed; he farms his own food, taking particular delight in growing potatoes.

Not only is tribal food sovereignty vital from a health standpoint, climate change makes the issue one of survival, Faith said. Out of the 400,000 acres of cropland across Standing Rock’s 2.3 million acres, Faith is working toward addressing the future.

“Homegrown is the future for a lot of areas in Standing Rock,” Faith said. “Our agro-business hasn’t even gotten to first base. Climate change is going to be here before we know it and we need to get back to the basics.

“The Sundances, the ceremonies, the language, food sovereignty, they’re all trying to come back. They’re knocking on our door. When climate change happens we have to go back in time. Today, we are trying to reestablish that. Differences aside, we have to come together. Natives and non-Natives all have to live together. We can learn from each other.”

Greenhouses, or hoop houses – some already standing – could be maintained year-round using a mixture of solar and wind energy and conventional methods so that Standing Rock residents will have access to fresh produce 12 months of every year. Venison and bison meats can be cured, stored away for the leaner months. Old stone cellars in Cannon Ball have been renovated to help.

“Mother Nature is ready to be harnessed,” Faith said. “I see it coming together with these grants. We need to get back to a holistic way of life and teach people that this is how we did it back in the day.”

Petra Reyna

Petra Reyna is the director of Title VI nutrition for the elderly and support program at Standing Rock, and it is with the elderly that her goals for establishing tribal food sovereignty begin. She is striving to teach the younger generations the joys of being self sufficient and healthy through small-scale at-home farming.

Once an aspiring doctor studying at South Dakota Medical School, the dean expelled her even after she received all passing grades. Dr. Lars Aaning, a retired surgeon in South Dakota who surrendered his medical license for patient advocacy, verified Reyna’s account.

She was expelled because she cared too much for patients, and because she challenged a disjointed system based entirely on time equals money. Her dream was to become a doctor and return to the reservation, a notion that doctors in medical school found controversial.

“I’m a Lakota, and if I change who I am, then I am no longer a Lakota and not good for my people,” Reyna said.

“I really believe that when you look at the power structure that’s what I ran into in South Dakota. I always talked about going back and helping my people. But the stereotype is that we’re primitive people and one of the things we learn is that we have people who want to come in and save us. The thought and process of assimilation – the notion of America – everyone becomes homogeneous. In theory, everyone moves toward being part white. For me to speak like that is really contradictory toward the doctors helping me, the doctor’s job was to save me in their mind. I was supposed to go into mainstream society and make money and assimilate.”

Six months shy of graduation and approximately $200,000 in debt, Reyna chose to return home and focus on holistic approaches, digging down into the root causes of widespread diabetes and cancer. She – and others – discovered that a major factor outside of broken and impoverishing federal promises was diet: frozen pizzas, McDonalds, potato chips, convenience food delivered by overpriced shipping companies. A severe lack of wholesome food for the nearly 9,000 residents inside Standing Rock was exacerbating health problems.

With annual costs between $500,000 to $1 million to run her Title VI program in Standing Rock, she’s looking for grants to help expand the program to include everyone. Some monies may come from the $380 million Keepseagle settlement, a class action suit led by farmers and ranchers who were denied loans from the USDA in the 1970s. Her chances may be slim, the lawsuit stemmed from Standing Rock, but there are more than 500 tribes in line waiting for disbursement.

She’s been awarded a $25,000 grant for teaching history of traditional foods, and has turned to NDSU, the North Dakota Local Foods Alliance, and the Tribal Food Sovereignty Summit for help to fight centuries of oppression and control.

“This has a long history and the basis is if you starve people, it’s like a war tactic, that’s how it started by killing all the bison,” Reyna said. “To starve the people into submission. To me, that tactic is still in the back of the government’s mind. We’re still seeing it. What the government has done to us it’s going to happen to everyone else. We’re seeing food deserts, even in cities and it targets certain areas and there’s no concept of sharing or taking care of each other in the U.S. anymore.”

When the dams were built the tribe was promised free electricity, she said. The promise was never realized as many Natives pay higher utility rates and live in poorly insulated FEMA or temporary housing, which forces electric bills in the winter months to skyrocket. As of 1983, more than $818 billion had been pocketed by the U.S. Treasury from one power plant relying on hydropower alone, according to a Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin conference proceeding minutes.

“The more modern day aspect of the system that affects everyone is just convenience,” Reyna said. “My master’s degree focus was on food and I learned from my research that when people lose their cooking skills they don’t know how to buy fresh foods and prepare them and we’re seeing this in the younger generation.”

Some children in Standing Rock are assured only two proper meals a day at local schools and don’t know where their evening meal will come from, Reyna said.

Although the program for tribal food sovereignty is dependent on creating interest through education on how to grow family gardens, others in the community are experimenting, mixing science and seeds.

Nathaniel Brown and Sue Isbell

NDSU/Sioux County Extension agents, Nathaniel Brown and Sue Isbell, have been collaborating on several grant-funded projects: USDA Specialty Crops Block Grant, CDC High Obesity Program, and Family Nutrition Program. The Extension Office provides education and hands on learning opportunities through community gardening, youth activities, science camps and workshops, and nutrition education.

With the community gardening, hoop houses have been constructed for community members for home gardening. Farmer’s markets are scheduled to distribute produce grown by community gardens, and the office is piloting new methods of gardening: aquaponics, hydroponics, aeroponics for Sioux county. The Extension Office grows tomatoes, cucumbers, cabbage, strawberries, squash, apples, onions, and a variety of peppers.

Charles “Red” Gates

A third program – the first initiated at Standing Rock – to combat hunger called the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Food Distribution Program is run by Charles “Red” Gates. Everyone calls him Red, he said. He hesitates to call Standing Rock a food desert because food is available, but most of the food available isn’t healthy.

“That program was literally killing a lot of our people because of the food we were being forced to eat by the government,” Gates said.

At a field hearing on February 26, 1990, Gates opened canned beef to show the nation what Natives were receiving in lieu of the treaties and handing over land to the federal government. Some women threw up at the smell, he said. Surplus beef-like chunks were packed with lard, red blood vessels, and ligaments – not good enough to feed a dog, one politician said at the time.

The laws changed, Gates said. Standing Rock became the pilot program for the nation. Apples, oranges, grapefruit, carrots, onions, red potatoes, and ground beef became available.

“That began the long journey to where we are now,” Gates said. “Back then it wasn’t called food deserts, it was called areas of hunger. People living in the United States of America were actually going without meals. Mother Earth gives us healthy food for a reason and we’re poisoning it, and we need to get back to healthier foods.”

Since before 1990, he has been fighting to get fresh produce and meats into the reservation as supplemental sustenance for low-income people. Initially he was challenged. People were afraid all assistance would disappear if the tribe complained, but step-by-step he has successfully helped change laws all the way to the most recent Farm Bill.

“That was a big, big win for us,” Gates said. “Now we get to sit down with the federal government and tell them what they need and want. We’ve also been able to convince the younger people to not be afraid to speak up and learn about nutrition. I see that happening.”

The Farm Bill also allows for two-year funding grants, Gates will no longer have to apply for assistance on an annual basis, he said. Since the creation of Standing Rock’s casino in the 1990s, the tribe has always been able to pay 25 percent of the costs for his program, he said.

“The food industry did not put a lot of thought when they started to use the canned goods, frozen foods, the pizza, we are all pretty much addicted to some of that,” Gates said. “And we want to change that. We now get bison in a frozen pack; we get healthy chicken. Our food package is probably one of the healthiest food sources in the nation or in North Dakota.”

The program serves 1,000 households on the reservation, of which not all are Natives. Food is distributed once a month, by warehouse and by semi truck to those without transportation, which can be a problem.

“We make sure they’re eligible, but the problem is that this system is kind of old fashioned,” Gates said. “They have to take their food for the whole month and sometimes it leads to waste.”

He hopes to open up a type of warehouse grocery store where those who are eligible can obtain fresh meats and produce on a more frequent basis, Gates said.

Hope for the future

Pete Red Tomahawk plants with his grandchildren, and their smiles and laughter give him hope for the future. He teaches them to tie knots in a rope, and how to plant three potatoes under each knot. Come harvest, the children race to dig up the most bló, or potatoes, which he takes home to fry.

“I think what Petra and Pete are doing is going to catch on,” Mike Faith said. “Getting the youth involved and the stories on how they need to depend on Mother Nature. All of this could also be passed on through the school system. They’re opening up the eyes of people in the ways of looking at ‘Why don’t we just grow our own?’

“The dependence days are behind us.”

[Editor's note: follow this link to the first story by HPR on North Dakotan food deserts].

February 23rd 2026

January 12th 2026

November 18th 2025

November 12th 2025

September 16th 2025

_(1)__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)