Live and Learn | March 9th, 2015

I’m trying to think “intervallically.” No, it’s not the new math or a metaphysical dimension in the space-time continuum. I’m just learning to play the piano. I never took piano lessons growing up, and when I tried it for the first time as an adult, it didn't take. I memorized the individual notes in every piece, but each additional song I learned replaced the one before it. After nearly two years, a handful of music books and dozens of pieces of music, I could perform a grand total of one song: the one I had just learned (it was a thankfully brief recital). This time around my teacher is getting me to see musical intervals, that is, the relationship between the notes, the chords and the structure of the music. For me, thinking intervallically means finding the patterns in the music.

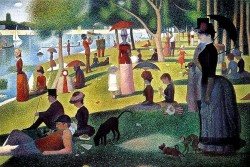

Across disciplines, in humans as in nature, the pattern is preeminent. In the eye, a single red, green or blue “cone” can’t see color; only the pattern of signals from all three allows us to discriminate wavelengths. Look closely at Georges Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” and you see nothing but individual specks of color. But step back to reveal how the dots create patterns and you have a masterpiece. In cells, one amino acid left off of a nucleotide chain, or one too many copies of a gene along a chromosome undoes the pattern and can lead to devastation for the organism. In the brain, a single neuron can’t tell us anything about how we think or achieve consciousness. But the overall pattern and location of neuronal activity reflects whether we are awake or asleep, depressed or elated, if we are looking, listening or remembering, perhaps even if we are lying.

We know that memory works best when you create a pattern to connect the information. Ironically, we know this because the pioneering psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus failed to find the limits of his memory because he was trying to remember meaningless nonsense syllables. We extend memory when we connect or “chunk” items together into patterns, making new wholes out of the individual parts. The movement of individual drops in the ocean doesn’t describe the action of a wave. Physicists know that particles behave differently when viewed as discrete entities versus a continuum of waves.

Even highly practiced skills like reading depend not on the individual items like letters, but the context of the sentences and words. You can manage to read your aunt’s scribbled handwriting or even sentences where entire words are jumbled up: “tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.”

Patterns are so important that our brain seems programmed to search for them, sometimes finding patterns where none exist or switching between alternate interpretations of a pattern that doesn’t change. A simple line drawing of a 3D cube will seem to flip-flop in depth as our brain searches for the “correct” meaning from the unchanging pattern.

Carl Jung said that humans have a tendency to find “archetypes” or meaningful patterns that persist over time: for example, masculine and feminine, or good and evil. In social psychology, stereotypes are ways of thinking about people or situations that are built on patterns of information, often an incomplete pattern and sometimes leading to dire consequences such as prejudice and discrimination. Recently a department store was forced to remove holiday wrapping paper from shelves because a shopper complained that upon close inspection the pattern looked like tiny swastikas.

Even children and infants respond to patterns such as those in language and music. When a four-year-old says, “Uh oh, I breaked the glass!” he has demonstrated the pattern for forming past tense in English, despite not yet attending “grammar” school or having diagrammed a single sentence. And long before they learn any particular language, babies recognize and respond to the musical qualities of speech. That sing-songy “motherese” we use when talking to babies emphasizes the melodic pattern; the words are irrelevant. It’s a good thing too, because I doubt the lullaby would be as effective if babies understood the lyrics “When the bough breaks the baby will fall…” The melody, the pattern of notes, is what gives the emotional meaning. As with reading, musical notes can be inserted or deleted, and whole melodies transposed into another key, but the pattern remains the same and both adults and infants recognize it as such.

And so I am trying to get my brain to convince my fingers to find the patterns hidden among these 88 keys. Or perhaps it’s my fingers that need to convince my brain? All I know is that this is going to take some time and lots of effort. You know what they say about how you get to Carnegie Hall, right?

[Editor’s note: Dr. Nawrot is Professor of Psychology and Director of the Child Development Lab at MSUM. She earned a Masters degree and a Ph.D. from the University of California Berkeley, and has been working on her M.r.s. and M.o.M. degrees for nearly 20 years.]

January 15th 2026

April 3rd 2025

March 15th 2025

March 15th 2025

December 19th 2024

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)