News | June 12th, 2019

THE BADLANDS – “I just want to flip the proverbial bird to North Dakota as I leave,” Sarah Gulenchyn said. She took a last drag off her American Spirit – burned quick to the filter – before stamping it out. The door to her 1989 Toyota 4Runner creaked loudly. Rust claimed much of the siding, but nicknamed the “Zombie Toyota,” the 30-year-old pickup refuses to die.

Sliding behind the steering wheel Gulenchyn – an engineer and oil field project surveyor – is leaving the state after she tried to pursue a case of harassment.

“I’m an old salty dog,” Gulenchyn said. “I’ve grown to love North Dakota, the weather and the summer. I love storm chasing. I really wanted to settle down and start farming or gardening on a larger scale. I would have lived here for the rest of my life, pay my taxes.

“But it is so racist here.”

Part Jewish, part Lakota Sioux, Gulenchyn now approximately 42, ultimately filed a complaint about her former manager Phil Ireland at LW Survey with the North Dakota Department of Labor and Human Rights in November 2017. She originally went to corporate managers, but her complaints went nowhere. Evidence was difficult to obtain.

“I had to tiptoe around the puddles of his emotions,” Gulenchyn said. “It was like carrying around a 180-pound stone all day. The only relief from his ongoing aggression and escalating abuse were the days I was assigned to work on other projects, completing more than 11 miles of corridor topographic and control surveys. It was these days of respite in solitude, hiking through the Badlands just east of beautiful Teddy Roosevelt National Park, that I felt truly happy and safe.”

At first, Gulenchyn tried to resolve the issue with LW Survey privately and settle for $95,000. “And they basically just told us to go pound sand. That’s when I filed with the Department of Labor.”

Linking her case to the #MeToo movement, Gulenchyn, who worked for more than 18 years on Alaskan pipelines, said the treatment she receives as a woman in a so-called “man’s world” stemmed from being educated, part-Native, and most importantly, a woman.

“For three months I assisted him while being subjected daily to racial and sexist slurs about Native Americans and women, being called a ‘prairie n*gger’ and told ‘Women should learn to wear oven mitts, not operate computers,’” Gulenchyn said.

She hired an attorney in June 2017 and filed for quid pro quo sexual harassment, which also failed.

“It’s not like I walk around with a body cam,” Gulenchyn said. “I feel I am treated in two different ways in North Dakota by men on the job. One is they think you are a feeble minded woman, and two, they’re intimidated and they feel threatened.

“Its cutthroat out there. You have to pull a knife out of your back every day. It’s a big dick-swinging contest.”

Her North Dakota story is only one chapter in a 20-year history of sexual harassment, from Alaska to the Badlands, she said. She endured harassment in Alaska, but never filed claims.

“There is an obtuse sense of entitlement that men who work in the oil fields possess,” Gulenchyn said. “For most men working in the Bakken shale formation, this is the first time in their careers they've worked remotely. This specific workforce is not a professional, college-educated group of individuals.”

So far in North Dakota few excluding the North Dakota Department of Labor and Human Rights case investigator believe her claims.

Gulenchyn’s dreams of being an engineer began during the summer of 1983 while watching an episode of Sesame Street themed: architect. A woman in a hard hat was standing over a set of blueprints. Men surrounded her, listening intently.

“I was sold, and knew I wanted to be like her when I grew up,” Gulenchyn wrote in a brief story about her life. “By midday the sun had dried the hay in the fields and it was time to work, so I reported my news to Grandpa as he hoisted me up on his lap in the tractor. This was our daily routine and he always let me drive.

“He approved of my new life plan as he filled the top of his thermos with coffee and handed it to me. Grandma didn't like me drinking coffee at such a young age, but Grandpa privately joked that ‘It will put hair on my chest.’ What he meant was that he had every intention of raising me to be strong and competent. He never treated me any differently than the grown men who worked seasonally for him on the farm. I was just one of the good 'ol boys.”

By the time she graduated with a degree in architecture from Cranbrook Institute of Technology, she found high-paying employment in Alaska. In 2001 she became an “i-man” or instrument operator on Alaska’s North Slope oil fields.

“I settled in Anchorage and buckled down, enduring life threatening temperatures and wildlife during periods of 24 hours of darkness,” Gulenchyn said. “It was tough work, but I was a good i-man – I was fast and I could handle the cold. And then it began, when pervasive sexual harassment permeated my entire professional life, and my innocence and wonder about the world around me was lost.”

Gulenchyn’s topographical surveys along pipeline routes in North Dakota were some of the best her bosses had ever seen, but the harassment she endured became too much, she said.

“Despite these ongoing, glowing performance evaluations, I was permanently laid off when the lead party chief hired his girlfriend,” Gulenchyn said.

Now, Gulenchyn is no longer looking for compensation. Leaving North Dakota for a new job elsewhere is bittersweet. Because of death threats she’s received, she doesn’t go under her real name on Facebook, and has blocked more than 200 people.

“As the #MeToo movement gained traction in October 2017 and has evolved into the Time's Up legal defense fund, I felt safe in coming forward and sharing my experiences,” Gulenchyn said. “I continue to be astonished that this current debate keeps moving forward, that zero tolerance policies are being put into place and enforced, and that actual change appears to be happening.

“It's too late for me,” Gulenchyn said. “I've suffered more losses than wins and am in the twilight of my career. You can only eat so many sh*t sandwiches in your life before you make a stand. It’s the first time and the last time. I would never put myself through this again.”

Sarah Piersol, the “North Dakota Redhead”

The most dangerous places for women in North Dakota are parking lots outside of bars in Williston. Sarah Piersol learned this in 2012 at Williston’s Heartbreakers strip club. She was escorted to and from her car every night after dancing and performing fire shows for “lonely” oilmen.

The money wasn’t bad. Not as much as the prostitutes who ordered condoms in bulk and could clear $1,200 for a night’s work, but it was enough for her to pay cash for a new car.

“I danced, wasn’t very good at it, but I was great at the fire shows,” Piersol said. “I ended up going out there to work because I used to do these fire shows. The owner of one of the bars said I should go out there to work, I could make a lot of money.”

Piersol’s fire shows included campfire fuel to create bonfires, blowing fireballs with Bacardi 151, and making flaming punches, she said. While working in other states she became known as the “North Dakota Redhead,” from the Peace Garden State they thought was next to Georgia, she said.

“I think you have to be weird to work up there,” Piersol said. “It’s a scary place for women. Period.”

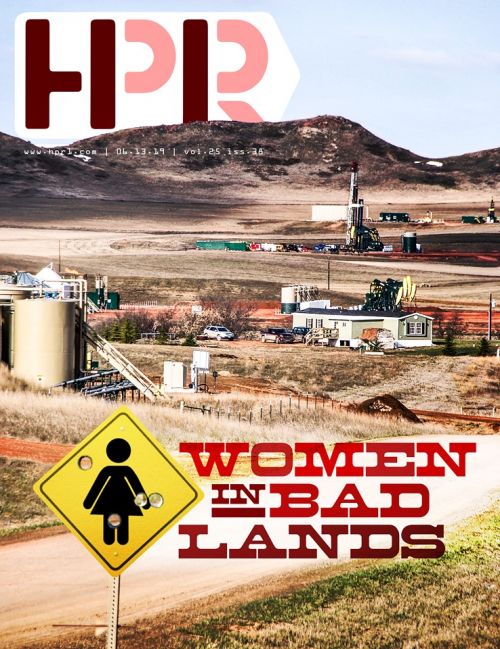

Although the initial 2008 Bakken “oil rush” has dwindled, the area is now producing more oil through conventional drilling and horizontal fracking than ever, approximately 1.2 million barrels a day. Not enough for Governor Doug Burgum who stated in 2017 that he wants the daily output to reach two million a day.

On the good side the oil boom has helped widen roads, bring in new hospitals, new events centers, plazas, and businesses in what was once a rural, agricultural center. Hopes that oil money will breathe new life into dying towns and villages are not improbable. In Williston, taxable sales and purchases exceeded $430 million during the fourth quarter of 2018 alone, according to the Office of the State Tax Commissioner.

On the bad side the economic upturn also brought in transient oilmen – by the thousands – living in man camps, the cartels with their drugs, sex trafficking, guns, violence, and oil lobbyists buying off politicians for pennies compared to more mature oil-producing states.

In 2012 when Piersol decided to dance in Williston, crime rates were already ticking upwards. Then, reports of assaults and rape had increased 400 percent from 2004, and would skyrocket to a comparative 600 percent by 2017, according to City-Data crime reports.

From the onset of the Bakken’s oil boom, crime doubled across the state, according to statistics released by the Disaster Center and compiled from the annual FBI crime report. In the year 2000 there were 169 cases of rape reported. By 2008 that number increased to 207, and to 256 by 2016. Aggravated assaults leaped from 294 instances in 2000 to 284 cases in 2008 and 1,365 reports in 2016. Violent crimes skyrocketed from 523 cases in 2000 to 1,903 in 2016.

Since the oil boom, the state’s population increased by 116,531, according to the Disaster Center, which between 2011 and 2015 made North Dakota the nation’s fourth youngest state, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Piersol said she was naïve when she arrived in Williston, but was one of the lucky ones as she had a protector. Quiet, good looking, and sensitive, he was a security guard known as “Cowboy” and he took care of her.

“You could tell he knew people,” Piersol said. “You could tell that Cowboy made it his mission to take care of us. I don’t even know his real name, and I don’t think he would tell people his real name. I don’t know what his story was, he wouldn’t share it.”

Even when she needed work done on her car he would insist on accompanying her because out there in the oil fields, “even the cops are corrupt,” Piersol said.

“I got lucky because I knew the right people, who knew people who knew people. And that’s a North Dakota thing. It’s all about who you know and not what you know. I can’t imagine a woman from out of state against people who think they can take advantage of her.”

Signs of possible bonded labor and sex trafficking arrived every day in a bus. Women mostly from the Ukraine and Russia would file off and set to work inside the strip club, she said.

“They literally have women who are stuck, I mean I worked with women who would show up in a van every single day at the strip club to work, and then they get picked up in the van to go home and they put all their money toward this guy,” Piersol said. “There’s even an episode about this in ‘Dexter’ where these showed these women who are forced into this ring in order to get their citizenship, well then they actually never get it. That’s true. It still exists. It is just allowed to exist, there is a lot of that.”

The woman she roomed with was 29-year-old American with “terrible daddy issues,” who watched the Disney channel every waking moment, she said. In 2012 she drank to relieve the stress of her job.

“I worked in a strip club so there were always guys who say ‘I’ll pay you 50 bucks if you f*ck me,’ and I would be like ‘Hey, you’re funny, keep making those jokes.’”

Laughter comes easily for Piersol. She took a sip of Jameson with her coffee and picked up a dollar bill off the table in a Fargo pub, a place she’s safe and comfortable. She wrapped a quarter inside, then used lip-gloss to make the flat end sticky.

“This is what we called a butt dart,” Piersol said. She held up the wrapped dollar bill. The goal of the thrower was to make the dart stick to the skin when thrown.

“Working where I worked it definitely wasn’t a career job, you show up, make your cash and leave. I think we just drank a lot, I think that’s how we dealt with it. There were girls that were so much better at this job than I was. The whole reason I liked dancing at the place I used to go was because we would literally dance behind the bar. Men would never get close to you; they could never touch you. You never had to deal with it.”

At Heartbreakers the atmosphere changed.

“I would always have to police it because I would get into trouble if the guy touched you,” Piersol said. “That could affect your job, and of course, they’re always trying to touch you. They can’t. You were always having to try and fight with them and say ‘You need to do this’ that was the most difficult part and it kind of took all the fun away.”

She challenged herself to turn clients’ sexual drives into meaningful conversations. Many men would open up and reveal broken-hearted stories.

“And I think a lot of that was to try and get me to be emotional,” Piersol said. “It was one broken heart after another.”

Wasté Win Young is a registered member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and has lived in the Bakken area. She’s a graduate of the University of North Dakota and now the mother of four, and to this day Win Young’s constant companion is fear, she said during a 2017 interview.

Fear for her children. Fear handed down to her at a young age. Tips on how to live include: never enter a public restroom alone, never go to a fraternity party, never go to New Town, Williston, or especially man camps.

Watch out for police. If stopped, travel to a well-lit public spot. She drives an hour every day to work and her vigilance is constant, a part of her life.

One of the most shocking statistics related to human trafficking is that Indigenous women appear to be targeted, because perpetrators believe they can escape prosecution. White women are victimized at 8.1 per 1,000 while Native American women as 23.2 per 1,000, according to statistics compiled by the South Dakota Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault. Native women across the nation are ten times more likely to be murdered than the national average, according to the National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center.

More than half of Native women have experienced sexual violence in their lifetime, and primarily at the hands of non-Native perpetrators, and are twice as likely to experience rape, according to the same study.

Lesser human beings

Treatment of women in North Dakota's oil fields – whether from outsiders searching to strike rich or actual residents – is worse than the words human trafficking or exploitation imply, Sarah Gulenchyn said.

“Those that stood by and watched as Native women were abducted, or as a coworker mistreated a female employee, or as the stripper was forced into sex she did not want, are just as guilty as the perpetrators," Gulenchyn said.

Some women are treated as intruders into a “man’s world,” or as lesser human beings – rising crime statistics prove this – and those like Gulenchyn who are highly educated are treated as threats. The mistreatment extends to women from all walks of life, including Natives and law enforcement’s inability or tacit refusal to properly investigate cases like Olivia Lone Bear from the Three Affiliated Tribes, and countless others. Issues surrounding the missing and murdered Indigenous have only recently attracted lawmakers’ attentions in proposed bills such as Savanna’s Act.

“In my mind it’s all interconnected,” Gulenchyn said. “It all ties to MMIW [Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women] and the #MeToo movement.”

In a 2018 documentary entitled “Sex and the Oil City” by RT Documentary, Williston resident Windie Jo Lazenko said the rise in crime – especially against women in oil producing lands – is worse than horrific. Oil workers automatically presumed single women were prostitutes during the oil boom, she said.

Lazenko is a human trafficking survivor, and founder of victim advocacy group 4Her North Dakota.

“The thing that made North Dakota extremely vulnerable was the influx of men with a lot of money,” Lazenko said.

As a single woman in Williston, Sarah Piersol was propositioned repeatedly. Without her “Cowboy,” there were no safe zones, including inside a former boyfriend’s house when a man tried to break down her door while she was sleeping. Soon after the incident she discovered her former boyfriend was married, and she was forced to move out because the man’s wife and child were coming home.

“It was weird because you have this ratio of men to women that is just hugely outnumbered,” Piersol said. “I would go to the gas station and get gas and I would have eight guys hold the door open for me. When I was there people were nice enough to me where I felt – I mean it boosted your ego.”

As oil workers flooded the state’s sleepy towns, the ratio between men and women grew to as much as 20 for every woman, according to Williston city officials. With the men came drugs, gangs, sex, and even guns.

Since 2007, the state has received 347 calls pertaining to human trafficking and 109 of those calls became actual cases with 232 victims, according to the National Human Trafficking Hotline. So far this year six new cases of human trafficking – which includes the exploitation of males, females, adults, or children into the sex or labor industries, have been reported at the national level.

North Dakota began its task force to combat human trafficking in 2016, and national numbers differ from local information compiled by the North Dakota Human Trafficking Task Force. Since January 1, 2016 the task force has helped 322 victims, 251 of whom were adults, and 71 were minors. The majority of cases stem from the state’s western counties, according to the Attorney General’s Human Trafficking Commission North Dakota Office of Attorney General 2018 report.

Since the state’s task force began, 57 traffickers have been arrested, according to the North Dakota Attorney General’s report.

Human trafficking has raised law enforcement’s eyebrows since at least 2004 when the U.S. Department of Justice began a collaborative program to combat human trafficking, and North Dakota was no exception to investigations by the North Dakota Human Trafficking Task Force.

The Office of the Attorney General for North Dakota described human trafficking as: “a crime involving the exploitation of someone for the purposes of compelled labor or a commercial sex act through the use of force, fraud, or coercion. Human trafficking affects individuals across the world, including here in the United States, and is commonly regarded as one of the most pressing human rights issues of our time.”

For someone who has worked remotely in the oil and gas industry since the 1990's, the statistics are not new to Sarah Gulenchyn.

“The significant difference between Alaska's North Slope and the Bakken, for me, lies only in the fact that the North Slope is an international community of workers,” Gulenchyn said. “Men from Australia, Canada, Kazakhstan, Far East Russia and the Middle East - most of whom are not only well traveled, but well educated - are accustomed to remote work, travel and working with a diverse set of colleagues, including women.”

Gulenchyn was well paid for her work, earning up to $7,500 and paying $2,000 a week in taxes, she said.

“This is in stark contrast to North Dakota's workforce, many of whom have never seen paychecks exceeding $3,000/week,” Gulenchyn said. “The Nouveau Riche of North Dakota cannot handle this kind of overnight wealth, and black market industries of drug dealers peddling meth amphetamines and pimps selling sex workers target this uneducated demographic.

“The men who buy girls for sex don't see themselves nor the underage girls they pay for as victims. They see themselves as entitled to Native girls and their lands as the rise of white supremacy is normalized by Trump and his brand.”

February 16th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 27th 2026

January 26th 2026

January 24th 2026

__293px-wide.png)

_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)

__293px-wide.jpg)

_(1)__293px-wide.jpg)